From the Chicago Reader (October 11, 1988). — J.R.

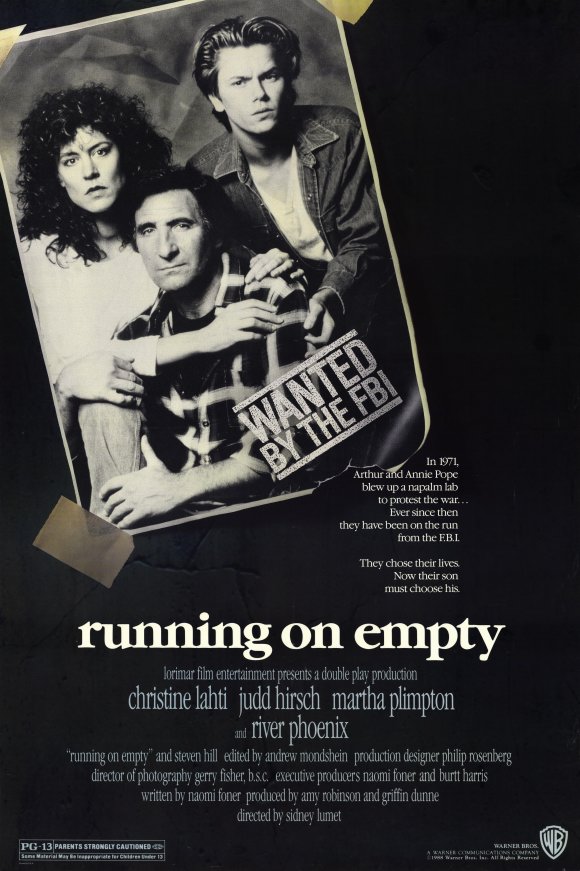

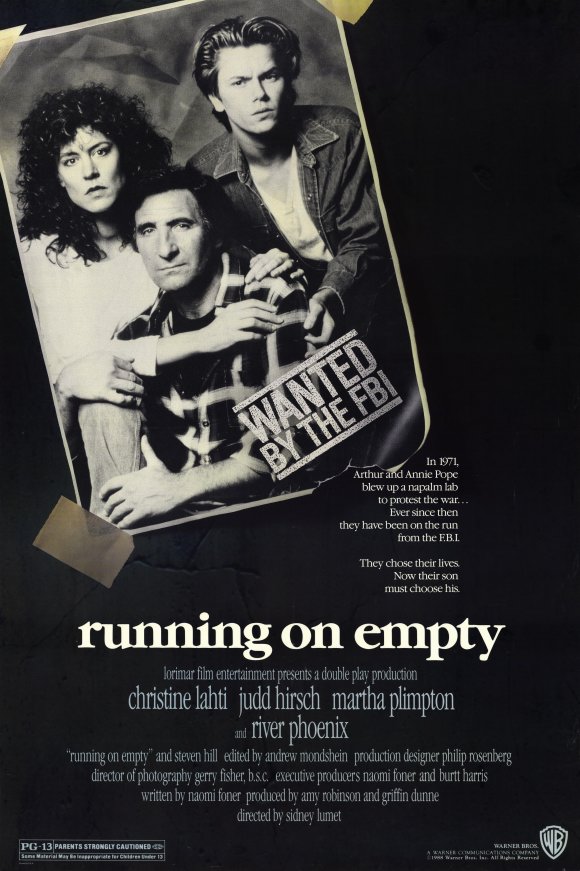

RUNNING ON EMPTY

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Sidney Lumet

Written by Naomi Foner

With Christine Lahti, River Phoenix, Judd Hirsch, Martha Plimpton, Jonas Abry, Ed Crowley, and Steven Hill.

It’s a truism that the distant past is easier to see clearly than the more recent past, so it shouldn’t be too surprising that current movie depictions of the 40s and 50s — Tucker, to name just one — tend to be more accurate, at least about the dreams and fantasies of those periods, than movies about the 60s and 70s. Paul Schrader’s recently departed Patty Hearst offers a salient case in point: it can only broach the early 70s through a sitcom or comic-book reduction of the way that radicals talk and think — a myopic 80s reading of the period that leaves a number of gaps in the picture. Schrader fills in some of these gaps by clever employments of style and attitude, the stock-in-trade of any current music video, but in the end one huge gap remains: Who was Patty Hearst? What was the Symbionese Liberation Army? Why should anyone be concerned with them? The attention-getting nowness of the film blots out any possibility for history or social observation; just as Schrader’s earlier Mishima seemed to have more to do with Las Vegas than with any reading of Japanese history or culture, his take here on 60s/70s radicalism seems mired exclusively in the preoccupations of the present. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 1, 1988). — J.R.

Except for The Red Shoes, this shot-by-shot rethinking of a dance performance by the Emile Dubois Dance Group, choreographed by Jean-Claude Gallotta and directed by Raul Ruiz, could be the greatest dance film ever made. Running only 65 minutes, the 1986 film is as much a sensual workout as Ruiz’s Life Is a Dream is an intellectual one; its celebration of pure physicality and movement is as exciting for film lovers as it is for dance enthusiasts. Using a Welles-inspired cinematography of wide angles, deep focus, shadows, silhouettes, and tilted perspectives, Ruiz and his gifted cameraman, Acacio de Almeida, join the spirited group of nine dancers not as detached observers or as competitors but as collaborators in the deepest sense of the word. Working through a continually mutable stage decor until the performance reaches a grand climax in the open air, by the sea, the film is almost as arresting aurally as it is visually, thanks to its natural sounds, music, and nonverbal utterances, all of which are superbly integrated with the physical movements. An exhilarating masterpiece, and in many respects Ruiz’s most accessible work of the 80s. (JR)

Read more

Read more

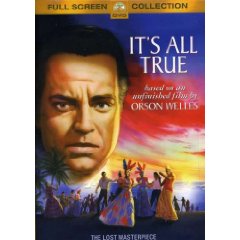

From my 2007 collection Discovering Orson Welles and the Chicago Reader (October 29, 1993). -– J.R.

I’m one of the people who receives an acknowledgment in the final credits of It’s All True: Based on an Unfinished Film by Orson Welles, but in fact I regret the contribution I made to this film. During a phone conversation with Bill Krohn, one of the writers, directors, and producers, Bill told me that one of the French producers, Jean-Luc Ormières, was looking desperately for a composer for the documentary who wouldn’t charge too much money. I suggested Jorge Arriagada — the Chilean film composer who at that point had written the scores for something like a couple of dozen films by Râúl Ruiz, a filmmaker I greatly admire as well as a friend — and Arriagada wound up getting hired for the job. I recall having heard that Arriagada mainly worked for Ruiz because he liked to do so rather than out of economic necessity, and this fact combined with Ruiz’s own Welles worship and Arriagada’s South American background made him seem ideal. Unfortunately, this conclusion was built on the common Anglo-American fallacy that Latin America is something like a single homogeneous culture — the same assumption, I presume, that years later would prompt Colin MacCabe, the producer at the British Film Institute of a series of national film histories on film or video assigned to various filmmakers, to assign the whole of Latin American cinema to one (admittedly very talented and knowledgeable) Brazilian director, Nelson Pereira dos Santos, yielding his 93-minute Cinema of Tears in 1995. Read more