From the Chicago Reader (November 7, 2003). — J.R.

Elephant

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed and written by Gus Van Sant

With Alex Frost, Eric Deulen, John Robinson, Elias McConnell, Jordan Taylor, Carrie Finklea, Nicole George, Brittany Mountain, Bennie Dixon, Nathan Tyson, Alicia Miles, Kristen Hicks, Timothy Bottoms, and Matt Malloy.

Gus Van Sant’s startling and brilliant Elephant — a film that follows the activities of several high school students before and during a massacre like the one at Columbine — has its flaws, yet its virtues so outshine them that the years he’s spent lost in the wilderness can be forgiven. His four previous features weren’t exactly dead on arrival, though his 1998 remake of Psycho came alarmingly close. But the filmmaker responsible for such fresh early shorts as The Discipline of DE (1978) and My New Friend (1987) and such exciting early features as Mala Noche (1985), Drugstore Cowboy (1989), and My Own Private Idaho (1990) was almost nowhere in evidence in Good Will Hunting (1997), Psycho, or Finding Forrester (2000) and only faintly discernible in the experimental feature Gerry (2001). (In between were two satirical features, the uneven 1993 Even Cowgirls Get the Blues and the more successful 1995 To Die For.) Read more

Okay, even though I’ve refused to place The Artist on any of my lists of end-of-the-year favorites, I’ve just finished reseeing it, and I have to admit that if I were a member of the Academy and could offer write-ins, Uggie the dog would be somewhere near the top.

Let’s be frank: we all have different thresholds when it comes to shameless bids for our affection, and these thresholds are invariably matters of taste. While I haven’t been able to forgive The Artist for pilfering and then brandishing a sizable chunk of Bernard Herrmann’s Vertigo score near its closing stretches to impart a sense of tragedy — even after I’ve forgiven Michel Hazanavicius for all his other outrageous breaches of period and silent movie syntax (in short, his diverse and mutifaceted ahistorical outrages), not to mention his abject appropriations of diverse narrative chunks from Singin’ in the Rain, A Star is Born, and Citizen Kane — I’m still periodically won over by some of his audiovisual ideas as acts of audacity and stylistic flourishes in their own right.

Above all, I’m flabbergasted by the performance of Uggie the dog, mutt extraordinaire, which has got to be one of the best canine turns in the history of cinema. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (December 1, 1987). — J.R.

Woody Allen’s worst film and second pure noncomedy — a desperate low-energy recycling operation — features four (or, arguably, five) cases of unrequited love among six characters stagebound in a New England summer house for about 18 hours: a suicidal depressive (Mia Farrow), loved by both her flamboyant mother (Elaine Stritch) and a middle-aged widower (Denholm Elliott), loves only an unfulfilled writer (Sam Waterston), who loves only the suicidal depressive’s best friend (Dianne Wiest), who doesn’t know who or what she wants. To add a little contrast, the mother is happily married to a physicist (Jack Warden), but just to make sure that we don’t jump to any wrong conclusions about this, the latter imparts to us the helpful wisdom that the meaninglessness of the universe is more depressing than the threat of nuclear annihilation (perhaps the key to Woody’s no-sweat politics). Wiest remarks at another point that she’s married to a radiologist, but she won’t let him x-ray her because she doesn’t want him to know what’s inside her. Most of the writing is on this glib and wretched level, and the laws of diminishing returns and what James Agee once called rigor artis set in with a stultifying vengeance. Read more

From The Soho News (April 8, 1981). I haven’t reproduced all of this column, preferring to consign most of the latter part of it to oblivion. — J.R.

My dream scenario runs roughly like this: J. D. Salinger finally relents and allows Jerry Lewis to direct a film based on The Catcher in the Rye (“Salinger’s sister told me if anyone would get it from him it would be me,” Lewis remarked in a 1977 interview), and civilization as we know it collapses. In the ensuing sociocultural upheaval occasioned by this deconstruction of two critical reputations, anarchy reigns supreme: mad dogs roam the street, The New Yorker shrivels to a cinder out of acute, well-mannered embarrassment; and all those distinguished gray eminences in my profession who fear and loathe Lewis for what he says about their own bodies and social discomforts — some of whom shrink in terror from Tati for the same reasons — run screaming off to the Hamptons and Berkshires to write their own fiction, never to return.

As long as such a personal fulfillment fails to materialize, I guess you might say I’m hardly working. So is the cinema today, at least the kind I care about. Read more

This is excerpted from my “Paris-London Journal” in the November-December 1974 Film Comment, written in August when I was starting work at the British Film Institute after living for five years in Paris.

I can’t recall now whether it was this review or my inclusion of Cockfighter on my ten-best list in Sight and Sound — or could it have been both? — that led eventually to Charles Willeford sending me a note of thanks, along with his a copy of his self-published book A Guide for the Undehemorrhoided, a short account of his own hemorrhoid operation. Not knowing Willeford’s work at the time — today I’m a big fan, especially of his four late Hoke Mosley novels — I’m sorry to say that I didn’t keep this book, which undoubtedly has become a very scarce collector’s item.

But first, before reprinting the Film Comment review, here is my capsule review of Cockfighter for the Chicago Reader, written almost three decades later and published in mid-August 2003: “Except for Iguana, which is almost completely unknown, this wry 1974 feature is probably the most underrated work by Monte Hellman (Two-Lane Blacktop). Read more

This is the first ten-best round-up I ever did for the Chicago Reader, which ran in their January 8, 1988 issue. Having recently been reading the Library of America’s mammoth collection of Manny Farber’s film criticism (which is coming out in September), I’ve become especially aware of how much one’s taste and preferences tend to change over time. Today, for instance, I suspect I would have placed Mélo in the number #1 slot, and probably wouldn’t include House of Games or Universal Hotel/Universal Citizen in the also-rans but would move them both up to the main list. The first photo, incidentally, directly below, is from Godard’s still woefully neglected King Lear.––J.R.

What is the meaning of a ten best list? For me, at any rate, it means a list of movies with the highest possible mystery quotient — the movies that fascinate me the most because they still have secrets to withhold. And the best litmus test that I know for determining this quality is repeat viewings. If a movie that knocked me out seems less mysterious after a return visit — as was the case with Broadcast News, Cross My Heart, and Orphans — then it doesn’t belong on the list. Read more

From The Movie, Chapter 108, 1982. -– J.R.

The earliest principles of editing shots together were perhaps no more simple or complex than those of bricklaying; they served, at any rate, to perform the same sort of basic architectural function. In an early narrative film by Georges Méliès, Le Voyage dans la lune (1902, A Trip to the Moon), elaborately staged tableaux in front of a stationary camera — the filmmaker himself called them ‘artificially arranged scenes’ — succeed one another through the medium of dissolves. A bevy of chorus girls waves goodbye to a rocket ship fired from a cannon (one tableau), the moon is seen approaching (another tableau, effected through a moving, artificial moon rather than a moving camera), and the rocket ship lands splat in the eye of the Man in the Moon (still another tableau). By the time Méliès was making Le Tunnel sous la Manche ou le Cauchemar Franco-Anglais (l907, Tunneling the English Channel), five years later, his visual structures were more complex, so that an entire narrative could proceed in the form of individual split-screen diptychs. In each of them, an Englishman and Frenchman attempt to cross the channel towards each other from opposite sides of the screen. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 3, 1992). A 2020 postscript to my remarks on For the Boys has been added. — J.R.

Looking at the big-time U.S. studio releases of 1991 — most of which enjoyed free supplements to their hefty advertising budgets from every branch of the media — we’d have to conclude that this was a year without enduring masterpieces. The best are intelligent entertainments, most of which faded quickly from memory. If I had to choose the ten best from this group, they’d be (in alphabetical order): Barton Fink, Beauty and the Beast, Bugsy, Defending Your Life, The Fisher King, For the Boys, Jungle Fever, Once Around, Rambling Rose, and Thelma and Louise. Equally good or even better are some new American pictures that didn’t get anything like the same national attention: Chameleon Street, City of Hope, The Deadman (only 37 minutes long, but better than most features I saw), Hangin’ With the Homeboys, A Little Stiff, My Own Private Idaho, Poison, Reunion, and Trust. The best American documentaries that come to mind are Butoh: Body at the Edge of Crisis, Inside Life Outside, Lines of Fire, Paris Is Burning, Private Conversations on the Set of Death of a Salesman, Sex, Drugs, Rock & Roll, and the videos of Sadie Benning. Read more

The following exchange appeared in Cinema Scope no. 8, September 2001. — J.R.

In the past, when I’ve interviewed filmmakers it’s been at my own initiative — or at least at the initiative of an editor making an assignment. This time, at the Buenos Aires Festival of Independent Film in April 2001, where I was serving on the jury and introducing Béla Tarr at some of his screenings, someone handed me a tape recorder, and Mark Peranson agreed to transcribe the interview afterwards if I would speak to Béla, who’s been a friend ever since Sátántangó. I hope that the casual grammar on both sides of this conversation doesn’t obscure too much of the meaning. (J.R.)

BELA TARR: […] In Sátántangó, we had a set. The doctor’s flat, it was built.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM: You know, that’s my favorite scene in the film.

TARR: Yes, but it was built! It is artificial, but you don’t feel it in the movie…

ROSENBAUM: Maybe that’s why I like it so much, because it’s in such a small space.

TARR: No, it wasn’t small.

ROSENBAUM: But it feels small in the film.

TARR: Yeah, sure.

ROSENBAUM: Was the actor playing the doctor a professional actor or a nonprofessional? Read more

The following is a one-page story submitted to Anthony Boucher, the editor of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, in April 1956, when I was 13, and accepted by him the following month, after a couple of rewrites guided by his suggestions. (The use of the drug “euphorin” was his own idea and invention.) Later that summer, on a family trip to the west coast, we (my parents and one or two of my brothers and I) actually managed to track down Boucher in his Berkeley home (we’d naïvely assumed that the address on his stationary was the magazine’s editorial office) and spent a very pleasant hour or so with him. The story was eventually published in the November 1957 issue (on the last page) and I received a check for $25 for my work. Later the story appeared in Spanish and Japanese translations in foreign editions of the magazine; I still have a copy of each. — J.R.

Now and Then

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

When the time machine started, I realized that I had forgotten to ask the professor its destination. But under the influence of a heavy dose of euphorin, it hardly mattered to me. To escape the tensions of the present, almost everybody I knew was taking the same or similar tranquilizers. Read more

I’ve been asked more than once to comment on Sylvain Chomet’s recent animated feature based on a Jacques Tati screenplay — something I’ve frankly been avoiding, for reasons that I’ll try to explain.

Last February 16, I received a very lengthy email from Richard Tatischeff Schiel McDonald, identifying himself as the middle grandson of Tati, and expressing his upset and anger about this film, which I was hearing about for the first time from him, and requesting that I make some of the information he was conveying to me better known if I planned to write about the film. I wrote him back the next day, and a week later he wrote me again: “I must admit to finding myself in a slightly uncomfortable position in making public the origins of my grandfather’s original l’Illusionniste script which until recently had been a very private family matter. My intentions are not to discredit my grandfather but hopefully by telling what is a very sad story I can shine a light onto a neglected chapter of his life that in part led to the creation of his professional body of work. My grandmother and all his stage acquaintances during the 1930’s/40’s always maintained that he was a great colleague as a friend and artist; he unfortunately just made a massive mistake that because of the time and circumstances he was never able to correctly address. Read more

Chen Kaige clearly intended this Chinese fantasy-action spectacle to top Zhang Yimou’s Hero, and I must admit that I prefer it to the earlier movie: the digital effects are sometimes excessive, yet Chen’s story of a loyal slave, his master, and a wealthy, seemingly doomed princess is more affecting, especially in the closing stretch. Chen’s original U.S. distributor, the Weinstein Company, ordered him to shorten the movie from its original running time of 128 minutes and then dropped it. (It’s worth recalling that his 1996 feature Temptress Moon was severely damaged by Miramax’s recutting.) Now Warner Independent Features is releasing the abbreviated, 102-minute version, and it’s well worth checking out. PG-13. Century 12 and CineArts 6, Esquire, Landmark’s Century Centre.

Read more

Read more

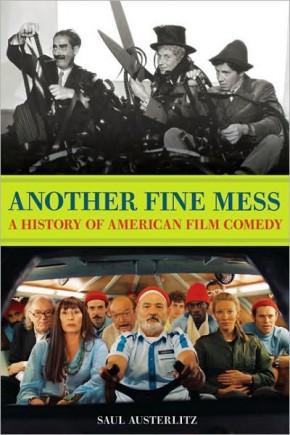

From Film Comment (November-December 2010). — J.R.

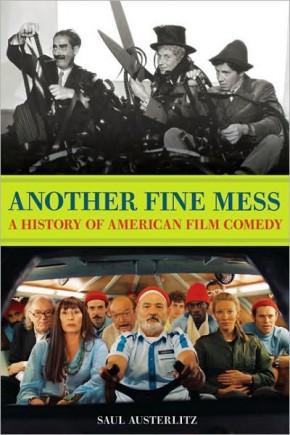

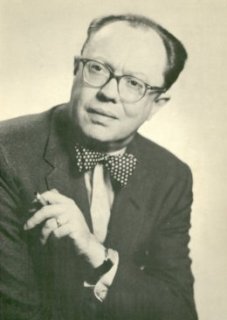

Another Fine Mess: A History of American Film Comedy

By Saul Austerlitz Chicago Review Press, $24.95

As an audacious and ambitious canonizing gesture, this highly readable critical volume comes closer to Sarris’s The American Cinema than it does to Thomson’s Biographical Dictionary of Film, if only because the author can always be counted on to have seen the work he writes about. Omissions are of course inevitable, and even though I don’t know Austerlitz’s age, I suspect that most of the lacunae I notice in the creative figures he selects for his 30 chapters and 105 shorter entries — such as Fred Allen, Danny Kaye, Martha Raye, and Red Skelton — are generationally determined for both of us; older and younger readers will come up with other missing names. But the amount that he actually covers is impressive.

Sometimes the organizational strategies get weird: the chapter on Dustin Hoffman, delving perceptively into the Jewish aspects of his persona, also manages to be a chapter about Warren Beatty. Some of the research is sloppy: Orson Welles couldn’t have “credited” The Power and the Glory as an “inspiration” if he maintained that he’d never seen it. Read more

Name: Jonathan Rosenbaum

Job title: film critic, teacher

Country: USA

Your votes

- Greed

Year: 1924

Director: Erich von Stroheim

- M

Year: 1931

Director: Fritz Lang

- Spring in a Small Town

Year: 1948

Director: Fei Mu

Comment: The most neglected great film on my list, at least in the Western world.

- Ordet

Year: 1955

Director: Carl Dreyer

- A Man Escaped

Year: 1956

Director: Robert Bresson

- Ivan the Terrible, Part II

Year: 1958

Director: Sergei Eisenstein

Comment: Like Welles’ equally worthy Touch of Evil, a monument to hyperbolic excess.

- PlayTime

Year: 1967

Director: Jacques Tati

- Vagabond

Year:1985

Director: Agnès Varda

Comment: Like Resnais’ Providence and Françoise Romand’s Mix-up, a masterpiece of magisterial juxtapositions.

- Satantango

Year: 1994

Director(s): Bela Tarr

- A.I. Artificial Intelligence

Year: 2000

Director: Steven Spielberg

Comment: Not only Spielberg’s best picture but also Kubrick’s; a collaboration between a dead director and a friend who survived him seems appropriate for a meditation on the differences between human and nonhuman, living and dead that comprises a searing allegory about cinema itself.

Further remarks: I’ve omitted Chaplin (City Lights, Monsieur Verdoux) Hitchcock (Rear Window, North by Northwest), and Welles (Touch of Evil, Chimes at Midnight) as “goes without saying”. Read more

From Sight and Sound, Winter 1975/1976; also reprinted in my first collection, Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism. — J.R.

Edinburgh Encounters:

A Consumers/Producers Guide-in-Progress to Four Recent Avant-Garde Films

The role of a work of art is to plunge people into horror. If the artist has a role, it is to confront people — and himself first of all — with this horror, this feeling that one has when one learns about the death of someone one has loved.

— Jacques Rivette interview, circa 1967

For interpersonal communication, [the modernist text] substitutes the idea of collective production; writer and reader are indifferently critics of the text and it is through their collaboration that meanings are collectively produced . . .

The text then becomes the location of thought, rather than the mind. The mind is the factory where thought is at work, rather than the transport system which conveys the finished product. Hence the danger of the myths of clarity and transparency and of the receptive mind; they present thought as prepackaged, available, given, from the point of view of the consumer . . .Within a modernist text, however, all work is work in progress, the circle is never closed. Read more