From the Soho News (August 11, 1981). This film is available now on Blu-Ray. — J.R.

Wolfen

Written by David Eyre and Michael Wadleigh

Based on a novel by Whitley Streiber

Directed by Michael Wadleigh

Tarzan, the Ape ManWritten by Tom Rowe and Gary Goddard

Directed by John Derek

I Hate Blondes

Written by Laura Toscano and Franco Marotta

Directed by Giorgio CapitaniHeavy Metal

Screenplay by Dan Goldberg and Len Blum

Directed by Gerald Potterton (opens August 7)

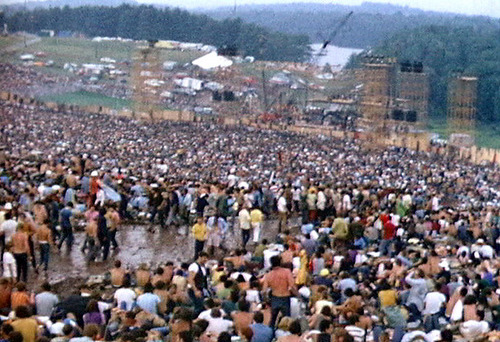

It was at the Cannes Festival in 1970 — a happy, unreal event — that I first came upon the awesome, utopian Woodstock, in 70mm and stereo, along with its pie-eyed director, Michael Wadleigh. He spoke beatifically about the convergence of art and politics in his press conference, and quite movingly dedicated Woodstock before its screening to the students who had just been killed at Kent State. After the movie, he passed out black armbands in the Grand Palais; I took one and wore it for a while. Eventually, some of the boutiques along the Croisette started selling them — which made it hard to know whether one was representing the New Left or Warner Brothers. I’m not sure that Wadleigh was entirely clear about this either. But I’ve been waiting over a decade to see his second movie, and Wolfen doesn’t let me down.

According to the current state of received ideas, rightwing formalism in movies (e.g., Escape from New York or Raiders of the Lost Ark) is “good clean fun,” not politics at all, while leftwing formalism (e.g., Numero deux) is supposed to be pleasureless politics, no fun at all. The incredible thing about Wolfen — a spectacular, metaphysical mystery-horror fantasy about New York that’s visceral and leftist in about equal doses, often at the same time — is that it builds its exciting, unfashionable politics largely through pungent sounds and images.

Some stunning uses of visual and aural subjectivity suggest what the world (specifically, lower Manhattan and the south Bronx) looks and sounds like to wolves, who are poetically linked to members of other vanishing and territorial dispossessed species, like Indians. Not everything in this visionary metaphor pans out politically or logically –- it’s not clear why blacks are frequent victims while, say, Indians are not –- but on a gut poetic level, it conceivably says as much as Jimi Hendrix’s version of “The Star Spangled Banner” does in Woodstock. In contrast to the reported uses of black and white footage to approximate ordinary canine vision in Samuel Fuller’s upcoming White Dog, Wolfen exudes some of the most gorgeous Day-Glo colors this side of solarizing –- many of them lushly reverberating tones on the multilayered soundtrack. And the fact that the mystery exposition is very gradual lets these achievements work at leisure on the imagination; not knowing what’s going on becomes an agreeable sensation, and a productive one.

Over the years I’ve come to regard Woodstock, paradoxically, as the Triumph of the Will of counter-culture – a visionary epic taking place in Heaven (“three days of love and music”). It’s not surprising that the offscreen terrorist group in Wolfen that is confused with the wolves (whose police informer turns out to be Wadleigh himself) is called Gotterdammerung, twilight of the gods. Wadleigh continues to see Woodstock as political, and in a recent phone interview stressed that he had nothing to do with the chopped-up, depoliticized Woodstock Revisited, with added commentary, that was shown recently on TV. (Considering his need of a large canvas, it’s understandable that he was opposed to Woodstock turning up on TV in any form.) Nor can he be said to have had everything to do with Wolfen, having been replaced by John Hancock as director (who remains uncredited) before the end of shooting. (Many writers were hired and replaced, too.)

Linking Wadleigh to Nazi propagandist Leni Riefenstahl may sound capricious and unjust; yet it’s hard to think of many other talented counterparts to an epic, lyrical naivite that is at once so exalted and passionately pluralistic in its reverence for collective strength and power. The fact that Wadleigh exalts an outsider’s society of mavericks and underdogs in both parts of his diptych has to be considered, too. It’s worth noting, however, that Leni also had a thing about wolves as superior beings — check out her Tiefland (1945) for copious illustration.

In fairness to the full range of Wolfen — which boasts a fine, understated performance by Albert Finney as a detective, with one of the best manufactured American accents I’ve heard since Olivier played Eugene O’Neill’s James Tyrone on the London stage — the movie has some of the delicate economy and reticence associated with the team of producer Val Lewton and director Jacques Tourneur in the 40s, especially in their luminously feline quickies, Cat People and The Leopard Man. Their poetic movies hold their monsters mainly at bay and offscreen — wispy notations in the mind’s eye that creep through parks, alleyways, zoos, and bedrooms, and linger in ambiguous pockets of quiet and dark.

One astonishingly beautiful sequence of Steadicam delirium turns us into a wolf darting down a narrow Manhattan street in what feels like the West Village, and pausing beside an iron railing. (Wadleigh mentioned Moby Dick as a reference on the phone, but it’s hard for me not to think also of Steppenwolf.) Later, there’s the luscious, liquid, even splashy kaleidoscopic Dolby effect of what Albert Finney and Diane Verona’s lovemaking looks, sounds, smells, and feels like, at least to the wolfy, multisensorial voyeur in all of us. Certain other moments aim for semisubliminal jolts, obtainable from climactic pay-off shots that are so fast you can barely tell what hit you, or, in one case, a beautifully inflected reverse-zoom to frame both Finney and Verona that punctuates a particularly jumpy moment. (Seeing Wolfen a second time with a weekend crowd, and sharing the same shreiks and laughs, was like riding a roller coaster with friends.)

Wadleigh told me his interest in wolves went back to when he was in medical school at Columbia. He discovered that man’s evolution caused his upper brain to crowd out the lower, making his senses decidedly inferior to those of wolves. Thus the lie detectors used by the police in Wolfen to spy on interviews — which look and sound a lot like the subjective wolf shots — represent man’s attempt to regain those powers, which are sensitive to nuances like heat change and psychological stress.

At different points in our conversation, Wadleigh cited both the film’s length and “resistance to doing things that were experimental” that led to his leaving Wolfen, without going into further detail. The current Cinefantastique reports that he exited “`for political reasons,'” meaning, “the exact reasons are still unclear”; what’s clear enough from still other sources is that they’re too complex and various to allow for any easy paraphrases here.

Even when it doesn’t make total sense, Wolfen is a giant among munchkins in the present batch of summer entertainments for the sheer grandeur and folly of its scheme (which includes everything from Carlos Castenada’s Don Juan to urban renewal to the monster movie’s “return of the repressed”). For its soundtrack alone — which deserves to be heard in a fully equipped theater — it is a worthy successor to Woodstock. And its warm, riffy uses of Gregory Hines as a hip black medical examiner and Tom Noonan as a spacey zoologist involve the kind of throwaway virtues that Val Lewton excelled in.

But the movie’s own favored vantage point is much more grandiose and myth- hungry. Its view is essentially the one we get at the movie’s beginning and end, from the towering top of a bridge — an Indian’s view of the Manhattan skyline, in more ways than one — and it turns us all into gods, conceptually speaking, or else Pygmies if we’re standing below. Either way, Wolfen is an inspired sensual orgy about something real, and a political thriller with eyes, ears, and guts — even if, like its beautiful animal heroes and heroines, it has to devour the brains of others.

***

By and large, Bo and John Derek’s Tarzan, the Ape Man — produced by and starring Bo, shot and directed by John — turns out to be about as absurd as one would expect it to be. Beginning with Tarzan’s celebrated jungle holler coming from the MGM lion, and ending with Tarzan (Miles O’Keefe, wearing a hippie headband and loincloth), a money, and a bare-breasted Bo as Jane strenuously trying to cavort and frolic in innocent R-rated bliss, this lethargic family romp tends to be a bit more childish than childlike.

The adventure-hungry kid in me strongly resented the absence of any treehouses. The grizzled adult longed for the anthropological comedy of Tarzan’s New York Adventure (an earlier, lighter version of Wolfen, in a way), whoile even the horny adolescent tended to concede that Less is More when it comes to the nondistinctive, San-Diego-central-casting charms of Bo Derek — as 10 and Playboy have each in related ways demonstrated. If anything charms here, it’s the smashing locations in Sri Lanka and the Seychelles Islands, and a few trees, monkeys, and elephants.

In order to get to these, though, you have to put up with acres of tireless, cranky scene-chewing from Richard Harris (the anti-Albert Finney par excellence), putting even the monkeys to sleep; pathetic tributes, complete with hippie body paint, to Apocalypse Now (with a matching Playboy spread); and an especially ugly form of lurching slow-motion every time the title hunk (who’s cuter than Bo — maybe because he has no lines) has to swing anywhere on a vine. The audience I saw this movie with hooted a lot, but they didn’t seem to be having much fun. Something tells me we all should have gone swimming on our own instead.

***

I Hate Blondes, by contrast, is more standard stuff — Italian boulevard farce, pure and simple — although it boasts at least two actresses (Corinne Clery, Marina Langner) who are sexier to me than Bo Derek, at least on a human level.The plot concerns Emilio (Enrico Montesano), a nebbishy ghostwriter of whodunits who seems closely modeled after Woody Allen’s persona, unable to peddle his own poetry while grinding out potboilers for the burnt-out celebrity author Donald Rose (Jean Rochefort, who’s closer to Spam than ham in his style of overacting).

Emilio gets involved with Angelica (Corinne Clery), a burglar after Donald’s possessions, and before you can say Jack the Ripoff, there are as many opening and closing doors as you’ll find at rush hour in a Feydeau farce — and lots of frantic slapstick that never slows down long enough for you to taste much of the bitterness behind the central premises. Good-natured and dumb about its patronizing fear of intellectuals (a conflicted emotion that Woody Allen’s popularity also seems related to), I Hate Blondes can be almost as brainlessly mechanical in spots as some of the sleaze-balls it ridicules — like Donald Rose, his publisher (Ivan Desny), and his agent (Renato Mori) — but at least it keeps moving under Giorgio Capitani’s well-paced direction.

***

If TV, according to the late Frank Lloyd Wright, provides chewing gum for the eyeballs, the supposedly rapid nonstop narrative flow of Heavy Metal — an animated movie based on the adult comic book — is like soft shewing tobacco for the mind: steady and dreamy and flaky, going nowhere. It’s the Yellow Submarine for the Me Generation, featuring a smorgasbord of graphic styles which nearly all seem a mite hastily drawn, and which all tend to promote (visually and aurally) the same basic tits & ass, s&m, b&d, blood & guts, Sturm & Drang, and rock & roll, in proportions, shapes, personalities, and quantities that quickly become indistinguishable, a mere quivering mass of jelly, despite the ostensible lineup of individual stories and profusion of individual artists. Overall, it’s a lot more consistent erotically than aesthetically — assuming that there’s anyone left who can make such a distinction.

The gory metallic mood evokes that of s-f writer Alfred Bester– apart from some charming extraterrestials, BEMS, and robots that I warmly associate with Dan O’Bannon (who collaborated on Dark Star, and wrote two of the episodes here), who remind me more of cuddly creatures in tales by Stanley Weinbaum and Edgar Pangborn. There are distances recalling the endless depths of the Krel in Forbidden Planet; and the barbaric blood-lust spectacle of pagan rites in Cecil B. De Mille is never very far away.

Another movie in the so-called apolitical “good clean fun” genre — probably ideal for adolescent boys who like to masturbate to mutilation, dismemberment, decapitation, and annihilation fantasies with racist trimmings from Soldier of Fortune and Terry and the Pirates, rather than to plastic-nubile foldouts from Playboy — Heavy Metal is no less simpleminded or gulpy about its own Jungian pretensions than Wolfen (which is easily ten times as much fun to sit through). But it’s rightwing instead of leftist, hence ideologically safer — acceptable in part to everyone, and a crashing bore.

|

“Stürme über dem Montblanc” – aufgebrochene Gletscherspalten, 1930. Im Film “Stürme über dem Montblanc” verkörperte Leni Riefenstahl mit der Astronomin Hella Armstrong eine moderne Wissenschaftlerin. Das Bild zeigt die im Frühjahr aufgebrochenen Gletscherspalten. Der Film von Regisseur Fanck besticht durch eindringliche Aufnahmen der Bergwelt. Lawinen und Gletscher gehörten bei den Dreharbeiten zum Alltag. |

|

Olympia, 1936: “Achter drängen sich an der Wendemarke”. Die in Kiel ausgetragene Segelregatta wurde im Teil 2 “Fest der Schönheit” gezeigt. Amerikanische Cineasten und Top-Regisseure zählen die Olympia-Filme Leni Riefenstahls bereits im Jahr 1956 zu den besten 10 Filmen aller Zeiten. |

|

Olympia, 1936: Goldmedaillengewinner im Turmspringen der Männer. Das Bild zeigt Marshall Wayne aus den USA, den Goldmedaillengewinner im Turmspringen der Männer. Anfangs werden im Film noch die Namen der Sportler genannt, dann nimmt die Bildgeschwindigkeit langsam ab, bis die Springer schließlich in Zeitlupe fliegenden Vögeln gleichen. |

|

Olympia, 1936: “Die Entzündung der olympischen Flamme”. Fackelläufer Anatol entzündete die Flamme in Griechenland an einem Säulenfragment. Mit den Säulen des Parthenon beginnt “Fest der Völker”, der erste Filmteil des Dokumentarfilms über die XI. Olympischen Spiele, die vom 1.-16. August in Berlin stattfanden. |

| Olympia, 1936: Sprung vom 10-Meter-Turm. Das Turmspringen bildet den abschließenden Höhepunkt des 2. Teils von Leni Riefenstahls Olympia-Dokumentation. Die Turmspringer wurden mit drei Kameras und unterschiedlichen Tempi aufgenommen. |

|

Leni Riefenstahl: bei Dreharbeiten zu ihrem Film “Tiefland”. Leni Riefenstahl bei den Dreharbeiten zu ihrem Film Tiefland in Krün im Karwendelgebirge. Erstmals arbeitete sie bereits 1934 an dem Projekt, das dann aber wegen einer Erkrankung der Regisseurin eingestellt wurde. Durch den Kriegsausbruch und viele Schwierigkeiten verzögern sich die Dreharbeiten immer wieder, die erst 1944 abgeschlossen werden konnten. |

|

Leni Riefenstahl: “Starfoto als Junta” im Film “Das blaue Licht”, 1932. In ihrem ersten eigenen Film “Das blaue Licht” übernahm Leni Riefenstahl nicht nur die Hauptrolle, der Film begründet ihre dritte Karriere als Regisseurin. Sie produzierte und schnitt den Film selbst, auch das Drehbuch schrieb sie zusammen mit dem jüdischen Filmtheoretiker Béla Balázs. Der Film gewinnt auf Anhieb die Silbermedaille auf der 1. Biennale in Venedig und verschafft ihr internationale Anerkennung. |

|

Haarstern, Malediven. Während ihrer zahlreichen Tauchgänge machte Leni Riefenstahl auch Filmaufnahmen. Ausschnitte des noch in Arbeit befindlichen Films über die Unterwasserwelt waren bereits im preisgekrönten Dokumentarfilm “Die Macht der Bilder – Leni Riefenstahl” von 1993 zu sehen. |