From the March 1980 issue of American Film. – J.R.

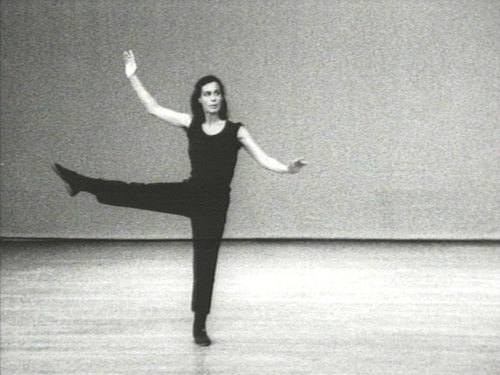

It’s pretty apparent to anyone who meets avant-garde filmmaker Yvonne Rainer for the first time that she used to be a dancer. But one probably has to see at least one of her four challenging features in order to perceive that she used to be a choreographer, too. And it’s only after one considers her in both these capacities that one starts to get an inking of what her viewpoint and her art are all about.

The first time I met her — three and a half years ago, at the Edinburgh Film Festival — Rainer reminded me in several ways of writer and filmmaker Susan Sontag. It wasn’t merely the somewhat glamorous positions that both women occupy on respective intellectual turfs. There was also a kind of spiritual resemblance that seemed to run much deeper: voice tone, appearance, wit, grace, and coolness masking an old-country sense of tragedy and suffering.

***

In Edinburgh Rainer delivered a lecture called “A Likely Story,” about the use of narrative in films. In the course of her remarks, she made it clear that her own “involvement with narrative forms” hadn’t always been “either happy or wholehearted,” but was “rather more often a dalliance than a commitment.” As she put it in a series of questions:

Can the presentation of sexual conflict in film, or the presentation of the experience of love and jealousy, be revitalized through a studied placement or dislocation of cliches borrowed from soap opera and melodrama?…Are faces such as belong to Katherine Hepburn and Liv Ullmann the only vehicles for grief and passion? Can a film achieve comparable impact through means other than these [faces]? And why in the world would one ever want to achieve an effect comparable to that wonder of art and nature, the smile fading from Hepburn’s face?

These are questions that are implicitly raised in all Rainer’s films, in one way or another. Most frequently, they are raised in connection with her ambivalent use of autobiography. On one level, Rainer uses autobiography as an intense form of critical self-scrutiny and exploration. On another, she deliberately omits most of the direct traces of this from her films, ostensibly asking us to respond to her narratives as if they were impersonal.

The logic of this method is, in a way, impeccable. It implies that we are all our own autobiographers — unwittingly or not. By removing some of the specific personal links that she has with her own material, Rainer obliges us, as individual spectators, to forge some personal links of our own in their place.

What emerges from this method is a kind of elusive candor or honest uncertainty — the same sort of dual aspect that one finds in the American-European, performing-choreographing sides of Rainer’s temperament. For spectators of her films, it can ideally lead to an analysis of emotions that is as rigorous as her own.

***

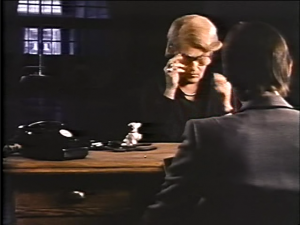

Although Rainer figures as a performer in all of her movies to date, her roles have become less and less central. In her latest film, for instance — shot in Berlin, London, New York, and Berkeley, completed in Boston late last year, and recently screened in New York — her appearances are secondary to those of writer and professor Annette Michelson.

Considering Rainer’s ambivalent feelings about stardom, she was understandably a bit put off when someone asked her whether the presence of Michelson in the film was intended as an in-joke. “Just the fact that Annette’s a film historian and critic and a lot of people know her doesn’t make it a joke,” Rainer pointed out recently, in the midst of discussing certain reactions to her film. “She’s an actress. It isn’t necessary that you know who she is in order to appreciate or follow what she’s doing.”

Rainer alluded to the offscreen voices of fellow avant-gardists Vito Acconci and Amy Taubin heard in the film. “I use people I’m very familiar with, so I know what they can do, and I know how they’ll sound doing it. I haven’t gotten into auditioning strangers — I’ve very bad at psyching out what someone’s potential is; I don’t understand that whole process. So I continue to use the people I’ve known for years.”

Regarding the political nature of Journeys from Berlin/1971, her latest film, I asked Rainer why she chose to deal with Germany, as opposed to the United States. “I lived there for a year,” she said, “and was very aware those things were going on” — referring to acts of the German government in 1977 that are cited directly in the film, as printed titles, including the imprisonment of anarchists Andreas Baader, Gundrun Ensslin, and Jan-Carl Raspe. “And right after I came back, two weeks later, Baader and Ensslin and Raspe were found dead in their cells. That was like the end of a whole era.

“So I was interested in two things: making some kind of treatment of the psychoanalytic situation — I knew it was not going to be a realistic thing — and my early associations with anarchist terrorism, or political violence as a subject, which goes back to my own background. I was raised by anarchists,” she went on, recalling her childhood in San Francisco, where she was born in 1934. “When I was fifteen, Emma Goldman’s autobiography was one of the great books in my life.”

Excerpts from a journal kept by Rainer between the ages of fifteen and eighteen are, in fact, read offscreen during portions of her new film — although, characteristically, the fact that it’s her journal is cited in neither her film nor the script. “The content of the journal is, in a way, in keeping with the thrust of the American woman patient played by Annette — the sense of that drive toward changing the self, and dissatisfactions with one’s own psychology, which are very endemic in American psychological practice.”

“The voices are kept separate,” she continued. “The only ones that are embodied are the patient’s and the therapist’s.” (Unlike the patient, the therapist is portrayed by no less than three people — a woman, a man, and a small boy. This recalls the deliberately confusing strategies of Rainer’s Film About a Woman Who… [1974] and Kristina Talking Pictures [1976], whereby characters are often split between several actors, including Rainer herself. In Lives of Performers [1972], her first feature, she took a somewhat different approach by assigning fictional relationships and intrigues to members of her dance group at the time, who used their own names.)

“All the other voices maintain their own identity,” Rainer went on. “But what they deal with, by the end of the script, is interacting and intersecting — as though the discussion were taking place in the identical space — although you know that it isn’t, because of the different contexts that are established. The soundtrack is extremely important in this film. It’s very detailed. The intention was to create an environment that you could visualize from the sounds alone.”

The images in Journeys From Berlin/1971 are repetitive and “almost incidental,” Rainer noted. During the first fifteen or twenty minutes, “you see everything you’re going to see.” There are a lot of tracking shots, including one that moves a long a mantelpiece which contains “everything that is referred to in the film” that Rainer felt she could represent in an object or photograph. “Because of the tracking, the relation of word, sound, and image is constantly sliding around. And you don’t understand the presence of a lot of images on the mantelpiece until later, when the patient is talking.”

For Rainer, in short, “talking pictures” is a medium where both words deserve equal emphasis. Her own list of major influences on her filmmaking seems to bear this out. It includes Carl Dreyer and Jean Renoir as well as a few contemporaries. “The obvious influence, as far as the camera’s concerned, is Warhol. Then there’s some of Frampton’s early work. And I guess Snow, in the use of language.”

Rainer’s latter reference is to Michael Snow’s five-hour epic about relations between images and sound, entitled Rameau’s Nephew by Diderot (Thanx to Dennis Young) by Wilma Schoen. When I suggested a relationship between a sequence in this film and her track along the mantelpiece, she nidded and said, “In my case, there’s no system. It’s the difference between m and Snow. He settles on a system for each of those sequences and follows it through. In my movie, you can’t predict what’s going to happen. You can only recognize things when they come up and make your own connections.”