From the Chicago Reader (July 20, 2001). — J.R.

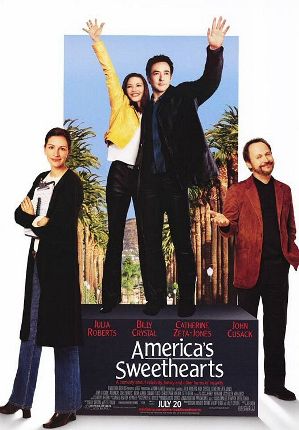

America’s Sweethearts

Rating * Has redeeming facet

Directed by Joe Roth

Written by Billy Crystal and Peter Tolan

With Julia Roberts, Crystal, Catherine Zeta-Jones, John Cusack, Hank Azaria, Stanley Tucci, and Christopher Walken.

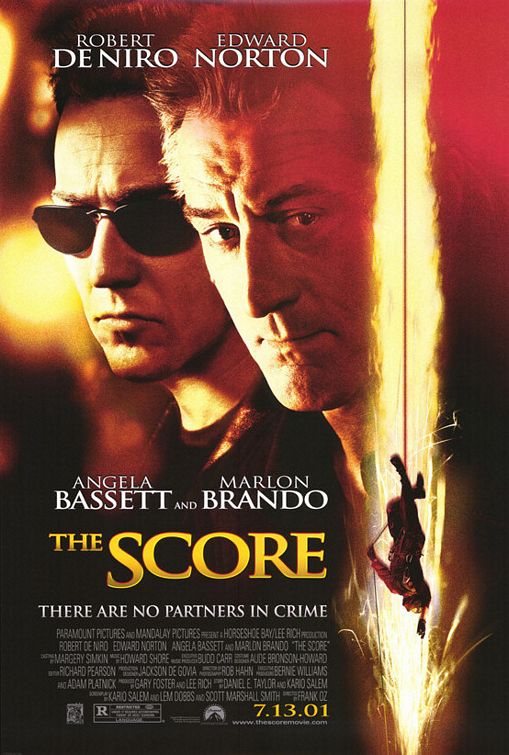

The Score

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by Frank Oz

Written by Kario Salem, Lem Dobbs, Scott Marshall Smith, and Daniel E. Taylor

With Robert De Niro, Edward Norton, Angela Bassett, Marlon Brando, and Gary Farmer.

“Talent means nothing if you don’t make the right choices,” says seasoned safecracker and jazz-club manager Robert De Niro in The Score, as he sets up “one last score” before he quits the game for good. It’s the only sensible thing anyone says in either this movie or America’s Sweethearts, a clunky ribbing of the movie industry, and whoever was making the big choices about these pictures should have taken it as advice. Both appear to be agents’ packages first and movies second, so that even though they’re trying hard to recapture the feel of Hollywood standbys — the heist thriller and the satiric screwball comedy — they seem to proceed from the premise that all that’s required is to throw the right number of “talented” elements in the same direction. It shouldn’t be surprising that the results often look more thrown together than crafted.

America’s Sweethearts begins with clips showing us Hollywood’s favorite movie couple, Eddie Thomas (John Cusack) and Gwen Harrison (Catherine Zeta-Jones), in some of their hits before she ran off with a Spanish bimbo actor (Hank Azaria), giving Eddie a nervous breakdown. I might have laughed if the clips were pointed or directed at something discernible, but the targets are so excessively broad and nonspecific that the effect is satire in name only. Much of the movie proper, which suffers from the same excess combined with vague targets, is set at a movie junket, just before the couple’s final feature is unveiled for both the studio head (Stanley Tucci) and the press — evidence of how farfetched the whole thing is. Billy Crystal plays a press agent honcho fighting to maintain spin control when the former couple isn’t even speaking. Julia Roberts plays the narcissistic Gwen’s sister and assistant, a former victim of overeating (as shown in some highly unconvincing flashbacks) who has dieted so that she’s now perfectly eligible to play the usual part of Julia Roberts and help Eddie get over his loss.

I like most of these actors — not to mention Christopher Walken as the hippie director of Eddie and Gwen’s last feature — so it’s depressing to see them stuck with an unfunny script and a director who tries to compensate by attacking the gags with a blowtorch. Crystal and Roberts are the only ones given coherent characters to play, but Roberts isn’t an integral part of the would-be Hollywood satire; she seems to function mainly as an afterthought, leaving me to wonder if she had her own writer on the set.

The heyday of the heist thriller was undoubtedly the 50s. John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle (1950) started things rolling in the U.S., then came Jules Dassin’s Rififi (directed by a blacklisted American) and Jean-Pierre Melville’s Bob le flambeur (both 1955) in France, then Stanley Kubrick’s The Killing (1956) back in the U.S., and finally Mario Monicelli’s Big Deal on Madonna Street (1958), a hilarious Italian parody of Rififi. Since then we’ve had mainly acknowledged or unacknowledged spin-offs of The Asphalt Jungle, including Melville’s Second Breath (1966), Big Deal remakes such as Louis Malle’s Crackers (1984) and the first half of Woody Allen’s Small Time Crooks (2000), and partial spin-offs of The Killing, such as Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs (1992).

That’s a lot of mileage from a few low-budget noirs and one comedy, so it’s not surprising that this subgenre is beginning to show signs of exhaustion. Part of the problem, I suspect, is the fear in Hollywood of anything original or related to the present, though production executives try to cover in part by referring to remakes as if they were tributes. And they shrink the number of characters while expanding the running times: The Score is 40-odd minutes longer than The Killing, yet it’s sparsely populated compared to Kubrick’s broad lineup of memorable character actors. All we get in The Score is the old safecracker and his prickly assistant (Edward Norton), the former’s girlfriend (Angela Bassett) and heist contractor (Marlon Brando), and a stray strong-armer (Gary Farmer, who’s wasted more spectacularly here than Bassett or Brando, playing a nondescript heavy that almost any other large-size actor could do).

Frankly, I’m not sure about any of the casting in this picture. De Niro does OK with a part that consists of a few cliches stuck together, though he can’t be blamed for not making the part fresh if the screenwriters didn’t give him an interesting character (I couldn’t believe for a second that he ran a jazz club — he returns from Boston and asks an employee how the group that played in his absence was, apparently unaware even of its name). Bassett as a flight attendant/torch singer is barely sketched in, and all we know about De Niro’s assistant is that he’s working as an inside man, plays a mentally challenged janitor as a cover, and is hungry for more respect. Brando, to be fair, gives more of a performance and less of a specialty cameo than we’ve come to expect of him, but again, the part as written is strictly standard issue.

Without any strong characters to care about, the movie’s protracted efforts to wring suspense out of an elaborate scheme to steal a scepter seem, well, protracted. Similarly, it’s hard to laugh at a Hollywood satire like America’s Sweethearts that hasn’t figured out what it’s satirizing, particularly since it seems vaguely modeled after a subgenre from the 30s. Both movies suggest that we badly need new subgenres, but we aren’t likely to get them if filmmakers keep looking to studio staples from 50 to 70 years ago.