A short review commissioned by Film Comment (July-August 2002), which left out the asterisk in the title. — J.R.

*Corpus Callosum

I recently read in a film festival report that Michael Snow’s new 92-minute feature was a bit longer than it needed to be. This conjured up visions of a test-marketing preview — cards handed out at Anthology Film Archives with questions like, “Would an ideal length for this be 82 minutes? An hour? Three minutes? 920 minutes?” For even though this may be the best Snow film since La Région Centrale in 1971 — a commemorative (and quite accessible) magnum opus with many echoes and aspects of his previous works — it enters a moviegoing climate distinctly different from the kind that greeted his earlier masterpieces. In 1969, the late, great Raymond Durgnat could find the same “mixture of despair and acquiescence” in both Frank Tashlin and Andy Warhol; today, on the other hand, avant-garde art is expected to perform like light entertainment.

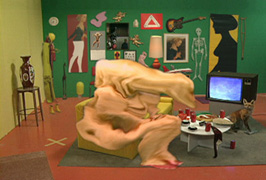

Up to a point, Snow seems ready to oblige with his irrepressible jokiness —- a taste for rebus-style metaphors (often banal) and adolescent pranks (a giant penis hovering over a blonde’s backside) that makes this the least neurotic experimental film about technology imaginable — the precise opposite of Leslie Thornton’s feature-length cycle Peggy and Fred in Hell. If the latter is a protracted meditation about technology as nightmare —- the nightmare we’re all trying to wake from (which is what James Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus called “history”) — *Corpus Callosum views technology in general, and DV in particular, as an occasion for vaudeville and slapstick. Instead of Oscar Levant in The Band Wagon carrying both sides of a ladder, we find the same woman putting on make-up at two separate work stations during the same pan, then appearing a third time walking in the opposite direction. Even when a dollop of gay s & m gets thrown in, the spirit is no different from that of the expanding bubble-gum bubble overtaking an entire room, like The Blob.

Over four pleasurable viewings, I’ve sometimes found this cornucopia exhausting, but always assume this to be a function strictly of my own limitations. Maybe it should be called a snowjob: an encyclopedia of effects like Rameau’s Nephew… (1975) with a “false alarm” ending like the one in the 1969 Back and Forth (with credits appearing less than two-thirds of the way through, succeeded much later by a fast rewind); a meditation on consumption as messy destruction, as in Breakfast (1976) and the opening section of Presents (1982); and an overall day-to-night progression (as in the 1967 Wavelength) eventually culminating in a return to origins, the first thing Snow ever did on film: a short piece of drawn animation in 1956 of a man’s leg stretching endlessly.

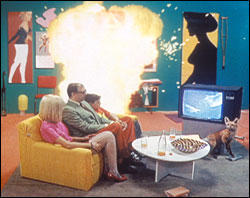

The title —- referring to the tissue that passes messages between the brain’s two hemispheres —- appears in the first shot on a green door that the camera backs away from and that people pass through as Snow, offscreen, audibly calls out instructions to them (as he does throughout the film). Then the camera moves towards a surveillance TV monitor above the door, showing the same door from the same angle; a tall man and short woman pass through it, and a reverse angle finds them with the others in a waiting area, where Snow directs them to various work stations and computers. From here on, the film is mainly an almost continuous left-to-right pan across this open work space, proceeding in an apparent loop — a cityscape visible through large windows behind the computers — while DV does all sorts of things to stretch, compress, combine, and otherwise distort the human bodies within this area. The main alternative space is a living room crammed with chintzy furniture evoking 50s record-album art and many shifting objects on the wall, where the tall man, short woman, and a boy who periodically exchange their color-coded clothes and their shapes hover around a TV on a sofa in the same sort of quasi-catatonic stupor shown by the office workers in front of their computers.

In his theorizing, Snow generally comes across like a metaphysician, shunning social meanings like the plague. Yet an interesting historical and social commentary arises from the differences between these two interior spaces: computer screens overtaking TV screens, a sleek contemporary work space that’s all windows overtaking a windowless domestic interior resembling a fallout shelter where 50s kitsch either replicates itself or blows itself up. It’s easy to forget Manny Farber’s early perception that Wavelength was above all about a loft and its implied memory. This film uses camera motion, diverse sound–image combos, photochemistry, violence —- the main staples of Snow’s previous films, with a few of his Walking Woman icons thrown in for good measure -— to tell us something about how and where we live, past and present, as well as what objectification can do to us and for us.

— Film Comment, July-August 2002