Recovering this piece, dated March 27, 2000, from an old floppy disk, I no longer have any recollection of who commissioned it or for what publication. [November 2012 postscript: It was the May-June 2000 issue of Film Comment.] — J.R.

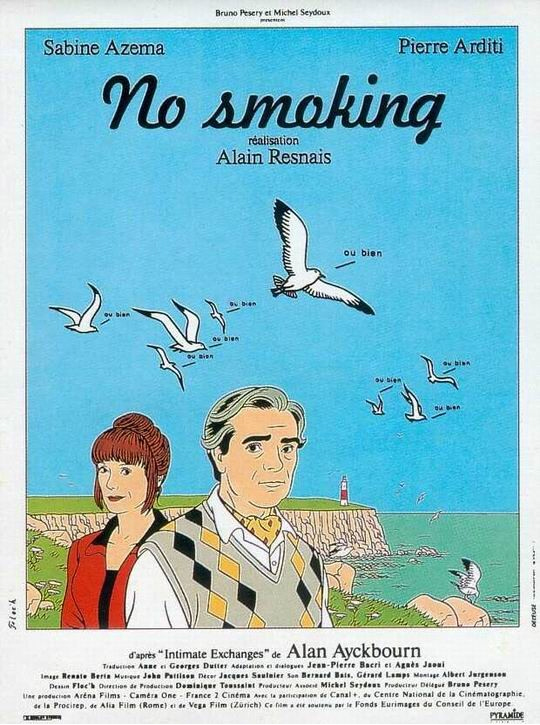

Keeping up with Resnais hasn’t been easy. One can find all his recent features on SECAM videos in France, but not the original English versions of I Want to Go Home (1989) or Gershwin (1992). Even Smoking/ No Smoking (1993) — a French adaptation of Alan Ayckbourn’s Intimate Exchanges, a cycle of eight English plays — is available only without subtitles, in a fancy one-box set.

Who would have dreamed that Resnais — supremely international with Hiroshima, mon amour in the 50s, Last Year at Marienbad and La guerre est finie in the 60s, Providence in the 70s — would have wound up a French regionalist in the 80s and 90s, culminating in Same Old Song? This outcome is obviously more a matter of fate than design. It’s not as if Resnais has stood still; the recent features show little of the emotional interiority of his earlier work, veering closer to farce than anything preceding them. Why haven’t most American audiences been able to chart these changes? (It was also in the 90s that an uncensored version of Resnais’s potent Les statues meurents aussi — his half-hour 1953 documentary about African sculpture, written by Chris Marker, with a final reel devoted to French racism against blacks — finally premiered on French TV, four decades after it was made.)

A profound yet mysterious cultural barrier related to national stereotypes seems operative. Though the arbitrary moves of the home video market are no doubt to blame for the neglect of Resnais’ melancholy 52-minute documentary Gershwin, American unawareness of I Want To Go Home can basically be attributed to the violent rejections of the film in France. The case of Smoking and No Smoking is quite different. This diptych swept the French Césars in 1994, winning best picture, director, actor, screenplay, and set design, and triumphed both commercially and critically. Yet the few English speakers to have seen these movies mainly find them strident and indigestible, artificial to a fault.

A surrealist at heart, Resnais repeatedly appropriates certain themes of science fiction — time travel in Je t’aime, je t’aime, subjective mind-trips in Marienbad and Providence, behaviorist speculations in Mon oncle d’Amérique, parallel universes in Smoking and No Smoking — without the usual generic trappings. In this respect he’s an aficionado of fantastique, a Cartesian realm without any ready Anglo-American equivalents. When an animated cat expresses the suppressed anxieties between a cartoonist father and daughter in I Want To Go Home, the American reflex to think “Roger Rabbit” isn’t very helpful; Otto Preminger’s Skidoo may actually come closer to the mark. The tenderness of this plaintive account of family deprivations, scripted by Jules Feiffer, largely pivots around the comic pathos of the French love of American pop culture — Gérard Depardieu as a Flaubert scholar who neglects his mother (Micheline Presle) and whose heart belongs to Bugs Bunny — and the American love of French culture (Laura Benson, who enrolls at the Sorbonne to study with Depardieu and escape her vulgar cartoonist father from Cleveland, delightfully played by songwriter Adolph Green), and the utter inability of the two modes to communicate. This culminates in a costume party in a country chateau that manages to evoke both Artists and Models and La règle du jeu. When the distraught father flees and, without a word of French, tries to get directed to the airport by villagers, he desperately resorts to lyrics from show tunes as his ultimate lingua franca.

Smoking and No Smoking chart the alternative outcomes that ensue among various Yorkshire residents — all of them played by Sabine Azéma and Pierre Arditi — after a housewife smokes or refuses to smoke a cigarette: 32 scenes in all, each one set in an exterior location that is visibly stage-bound, a painted backdrop. As Richard Combs put it, “The perversity is that this is not Ayckbourn reinterpreted as a French play, but Ayckbourn speaking French while still pretending to be English, with a confusing screen of different body languages and physical types.”

Resnais’ fascination with a highly theatrical cinema, first broached in Mélo, gets freakishly extended here, with two of the same actors running brittle, virtuosic relays between multiple roles. On the stage, Aykbourn’s plays were meant to be performed over eight consecutive evenings; eliminating the two most “English” scenes — a medieval pageant and a cricket game — Resnais commissioned Jean-Pierre Bacri and Agnès Jaoui, his subsequent writers on Same Old Song, to squeeze this into two two-hour features, to be seen interactively in whatever order the audience prefers.

In practice, Resnais reported that most French viewers hedonistically opted for Smoking first. And it appears that what they found more palatable than their Anglo-American counterparts is a principal identified by critic François Thomas as pivotal to Resnais’ later films — an alternation between affection and recoil, identification and distance, sweetness and bitterness reflecting the influence of Follies and other musicals by Stephen Sondheim. Mixing this up with national stereotypes is apparently more than any of us Yanks can fathom.

— Jonathan Rosenbaum