From the Chicago Reader, March 17, 1995. — J.R.

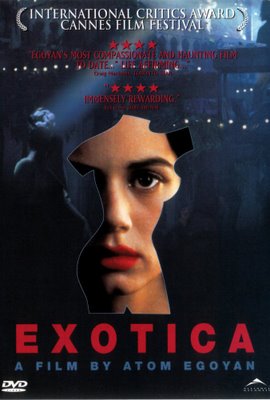

Exotica

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Atom Egoyan

With Bruce Greenwood, Elias Koteas, Mia Kirshner, Don McKellar, Arsinee Khanjian, and Sarah Polley.

The saddest parts of Exotica — Atom Egoyan’s lush and affecting sixth feature, a movie inflected like its predecessors by obsessive sexual rituals and desperate familial longings — are moments when money awkwardly changes hands. This film is every bit as allegorical as his Speaking Parts, The Adjuster, and Calendar — and every bit as concerned with a need for family surrogates as Next of Kin and Family Viewing — but it is only incidentally a movie about capitalism and its ability to pervert personal relationships. It does involve voyeurism, corruption, and a form of prostitution; all these things are conventionally associated with capitalism, but they’ve been around much longer.

Exotica has plenty to say about the modern world, including the psychological, social, and racial (even colonial) ramifications of “exotic” sexual tastes, but class difference isn’t a significant part of its agenda either. The personal and professional links forged between individuals — and there are very few relationships in this movie that aren’t both personal and professional — all seem predicated on forms of barter, as well as the assumption that everyone is, or eventually becomes, either a substitute for a missing family member or a virtual double for someone else. Within such a context, where the private and the public intersect as often as the personal and the professional, money is merely the glue, yet it always seems to tarnish the authenticity of the relationships of those involved.

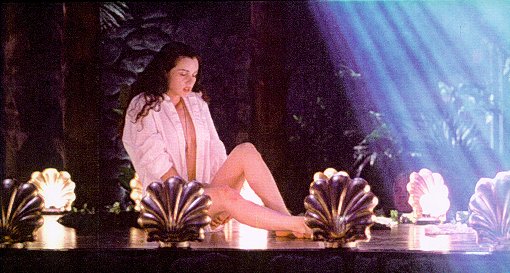

The most beautiful and interesting thing about the movie is its central set — a dreamlike upstairs nightclub called Exotica where women dance for and talk to male clients at individual tables without allowing themselves to touch or be touched. The cavernous reaches of Exotica imply a self-sustaining universe, yet this labyrinthine space is full of deceptive hierarchies. Perched somewhere above the tables, the fake palm trees, and the stage apron where the dancers make their entrances is a loquacious MC/DJ called Eric (Elias Koteas). Sitting at a counter, he introduces the dancers with an improvised spiel, conjuring up the fantasies each woman is meant to embody. To all appearances, he’s the ringmaster-god of this artificial and faintly colonial jungle paradise.

But appearances are illusory. Eric is stationed immediately outside a curious space, hidden by the decor, where the true boss of the establishment, a pregnant women named Zoe (Arsinee Khanjian), surveys the action in the nightclub below through apertures shaped like the nude bodies of women. But this is more than an office. It’s also Zoe’s home, and we eventually learn that she inherited it as well as the club from her mother. It’s a private womb inside a public womb, a sacred homestead inside a profane nightclub — or a profane homestead inside a sacred nightclub — and everything that Exotica is about radiates from its troubled center.

I’ve hesitated to review this film at length until well after its opening because it seems impossible to discuss what it’s about without describing the plot in some detail. Like other recent Egoyan features, Exotica intercuts between several apparently autonomous plot strands and then gradually reveals, via flashbacks and other revelations, how intertwined these strands are. (“I wanted to structure the film like a striptease,” Egoyan has said, “gradually revealing an emotionally loaded history.”) Though this convoluted story is anything but realistic, there are a number of facts about the characters and their past that most viewers won’t want to learn before seeing the movie. My advice to them is to skip the next section, which contains major revelations, and perhaps the section after that as well, which contains a couple of minor revelations.

Zoe, we soon discover, is a former lover of Eric, and it’s his baby she’s carrying; her current lover appears to be Chrissy (Mia Kirshner), one of her main dancers, who dresses in a schoolgirl’s outfit and caters every night to a man with special needs named Francis Brown (Bruce Greenwood). Chrissy is also a former lover of Eric’s, but she doesn’t know Zoe is carrying his baby or that another business transaction, sealed by a contract, hovers over the pregnancy — a dark discovery she (and we) makes only toward the end of the picture.

We also eventually discover that Francis’s particular need for Chrissy stems from the rape and murder of his daughter years before; shortly after this tragedy his wife, a woman of color, died in a car accident with his brother, who was crippled by the same accident, and Francis then discovered that the two of them were lovers. Every night before he goes to Exotica Francis picks up his brother’s teenage daughter and drops her off at his house, going through the charade that his daughter is still alive and needs a baby-sitter; after he leaves the club he collects his niece, drives her home, and pays her, until she eventually decides to stop.

In the daytime Francis, who’s a tax auditor, is investigating Thomas (Don McKellar), a smuggler of specialty items who operates a pet store as a front. In the film’s opening sequence Francis is looking through a one-way mirror at Thomas as he passes through customs with hyacinth macaw eggs strapped to his chest, while commenting on his behavior to a black customs official.

Sharing a cab into Toronto from the airport, Thomas is paid by his fellow passenger for his portion of the fare with a couple of ballet tickets instead of money–a chance event that inaugurates one of the film’s many repetitive rituals. Thomas turns up at the ballet that night, finds a young man of color looking for a single ticket, and sells it to him; they watch the performance together, Thomas eyes his crotch, and afterward Thomas insists on paying his companion back for the ticket because he got both tickets for free. The two following nights Thomas purchases two tickets to the same ballet, finds another young man of color to sell the extra ticket to, sits with him at the performance, eyes his crotch, and pays him back for the ticket afterward. The third such companion returns to Thomas’s flat for sex, and Thomas discovers the next morning that he’s a customs official who’s been tracking Thomas as part of his undercover work–the same man we saw in the opening scene.

Alternating with this story — a relatively benign and unneurotic account of “exotic” sexual cruising, at least in this movie’s terms — are the interlocking stories of Francis, Chrissy, Eric, and Zoe, some of which involve comparable repetition compulsions. Every night Francis and Chrissy go through the same routine at the nightclub: he talks to her about what might happen to her if he weren’t around to protect her while she performs a partial striptease in close proximity to him, almost touching him but never quite making contact; then he excuses himself to go to the men’s room, where he masturbates in one of the stalls. Via flashbacks, we learn that Eric and Chrissy originally met as members of the search party looking for Francis’s daughter and that this meeting apparently led to Zoe’s hiring Eric. Then, in a flashback that comprises the last scene in the movie (though it’s the earliest scene in the film’s chronology), we learn that Chrissy was the daughter’s original baby-sitter.

During the story’s present time, which covers three days and nights, Eric, distraught by the emotional intimacy he witnesses between Francis and Chrissy, goes to the men’s room to talk to Francis and persuades him to touch her, insisting that she wants him to. When he sees Francis touch her soon afterward, he throws Francis out of the club for breaking the house rules. Unable to reenter the club, Francis blackmails Thomas — by threatening to expose his smuggling operation — into visiting the club and seeing Chrissy in his stead, carrying a concealed microphone so that he can follow their conversation in his car. Once Francis confirms that Eric set him up the previous night, he resolves to murder him, but this plan is thwarted the following night when Eric confronts him outside the club, explaining that he was the one who found the body of Francis’s little girl; Francis responds by sorrowfully embracing him. It’s one of the last in a long string of encounters in which an impersonal transaction finally gives way to warmth and some form of shared recognition.

Hovering over this tortured story is the specter of incestuous desire, involving both the acknowledgment and the disavowal of that desire, and its relation to fetishism. In certain branches of Freudian film theory influenced by the late Jacques Lacan, this acknowledgment and disavowal is expressed in the phrase “Je sais bien…mais comme meme” (“I know perfectly well…but just the same”), and it’s been theorized that some version of this formula is at work in the suspension of disbelief experienced by every filmgoer, who knows perfectly well that the movie — the cinematic fetish, the object of desire — is illusory but agrees to believe in it just the same. It seems highly likely that Egoyan is aware of this connection: all his recent movies are largely about the subtle contractual deals that are struck between spectator and spectacle, between forbidden desires and the disavowals of those desires. So it would logically follow that they’re also movies about the experience of watching movies.

The “acknowledgment” in Exotica is contained in the familiar Leonard Cohen song “Everybody Knows,” which accompanies Chrissy’s stage entrance and opening dance every night at the club. The “disavowal” is signaled by a recurring home-video image of Francis’s wife holding up her hand to block Francis’s camera from taping their daughter. As Egoyan points out in an illuminating interview with Lawrence Chua in the March issue of Artforum, this image is “obviously a moment in Francis’s home video that has become fetishized and taken out of context. All through the film we see that moment of the mother holding up her hand to protect the girl from the father’s gaze. It’s a very threatening gesture — it seems like something in the middle of a violent or potentially violent encounter. At the end of the film we realize that in fact it’s just a very casual and humorous moment within the family. Francis has isolated that moment, and it has come to represent what he now feels toward his daughter.” And significantly, not long before the film finally demythologizes this image of disavowal, it offers us another one involving Chrissy — Francis’s surrogate daughter — that remains highly charged: Eric shielding her eyes when they find the daughter’s body in a field.

I’ve seen Exotica twice, ten months apart, and the two experiences were substantially different. At Cannes last year the overall prurience of the subject matter — highly evocative of the sort of puritanical repressions I associate with Ontario in general (such as its censor board) and Toronto in particular — tended to blind me to the warmth of many of the personal interactions between the characters, which exist in spite of their corrupt, ritualized professional relations. Considering the movie’s eroticism and the sense of carnal revelation that underlies the narrative structure, I suppose I responded with a certain prurience of my own: I began to feel I was being manipulated, encouraged to pursue a dirty secret that, when the denouement finally arrived, seemed rather paltry.

I can’t say this response was entirely eclipsed in my second viewing, but it became sufficiently complicated that I realized that the film’s key achievement is less its resolution or “payoff” than its stylistic means of getting there. Regarding the resolution itself, which is meant to spell out some of the origins of Francis’s sexual trauma, Egoyan admits in his Artforum interview that he came up with it only after mapping out most of the rest of the film. He calls the overall evolution of his script organic, but what makes the ending less than satisfactory is its willfulness — it’s as if he created an imaginary disease to account for a few symptoms.

But if this resolution seems contrived, its formal execution and effect are harder to fault. A central part of the movie’s dreamlike ambience derives from the fact that the camera is in motion in practically every shot — until we arrive at the final one, an extended take that shows a character retreating into the background and entering a house. Defining a static point of origin — comparable in a way to Zoe’s house inside the nightclub, built by her mother long before any of the film’s events take place — this lingering shot at the end of a flashback places a full stop after the fantasies that have dominated the film up to this point. But it’s a beginning as well as an end; the fixed image of a home finally says more about the film as a whole than any of the specifics of Francis’s particular trauma.

Prior to this conclusion the form of camera movement is generally a slow pan around the periphery of whatever’s being filmed, creating an overall sense of drift and reverie that implicitly links the nightclub with the pet shop and both of these central locations with the conversations between Francis and his niece in his car. (The only other movie I can think of that utilizes this kind of camera movement as pervasively is Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye, and it may not be irrelevant that the only other movie that uses Leonard Cohen songs to comparably suggestive and dreamlike effect is another of Altman’s best films from the 70s, McCabe and Mrs. Miller.)

What I like about these camera movements, combined with the exotic, erotic ambience of Mychael Danna’s score, is that they simultaneously implicate us in the characters’ fantasies and place us at some distance from them. We literally view the action from shifting perspectives, but the rhythm and direction of our drifting gaze seem to place us directly inside the obsessions of the characters. Like them, we’re looking for a final resting place that only a home and a family can provide — cruising in search of some notion of fulfillment that seems lost in the distant past.