From the Santa Barbara News & Review, October 24, 1985.–- J.R.

The Man Who Envied Women, introduced by filmmaker Yvonne Rainer, will be shown at 8 pm Monday, Oct. 28, Isla Vista Theatre II, Embarcadero Del Norte. Free admission.

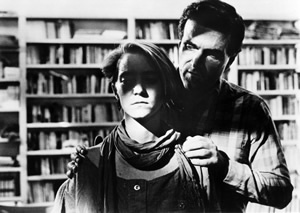

It doesn’t really do justice to Yvonne Rainer’s exhilarating The Man Who Envied Women to call it avant- garde — or even the best feature to date by New York’s most celebrated avant-garde filmmaker. To do that is to consign it to a gilt-eged ghetto presided over by experts. The fact that Santa Barbara is fortunate enough to be getting this movie in advance of both New York and Los Angeles — and with Rainer herself in attendance -– shouldn’tmean that we need any big-city explicators to crack the surface of her intellectual vaudeville. Admittedly, there’s enough theoretical discourse on display to choke a horse, and two actors rather than one (a favorite Rainer ploy) portraying the title character — a complacent, womanizing academic named Jack Deller whose second wife, a nameless voice, leaves him in the opening moments of the film. But the delightful thing about Rainer’s word and image salad is that its deliberate overload virtually guarantees that if we miss a particular gag or argument, we’ll find its near-equivalent lying in wait for us a few minutes later.

It’s ironic that as a modern dancer and choreographer, Rainer was known throughout the Sixties and early Seventies as a minimalist. For the past 13 years she has been making films of an increasingly multi-textual density — bombardments of ideas and sensations that may well reflect minimalism in some of their individual tactics, but goad us into multiple choices and divided loyalties as far as their cumulative sounds and images are concerned. Spectators who feel intimidated by the prospect of such an onslaught should be alerted that intellectual intimidation is an important aspect of Rainer’s subject.

Critic Bérénice Reynaud neatly encapsulates that subject in a single sentence: “Theoretical discourse, the making of images, sexual seduction, the making of money, all have one main purpose: to ensure control of the Other (the other sex, the other classes, the other countries).” In narrative terms, a torrent of thoughts and encounters comes to fill in the gaps created by a broken relationship. Or, more prosaically and politically, here’s Rainer herself: “This film is about the housing shortage, changing family patterns, the poor pitted against the middle class, Hispanics against Jews, artists and politics, female menopause, abortion rights. There’s even a dream sequence.”

Working with a script compiled from the speech and writing of over a dozen figures — including Raymond Chandler, Michel Foucault, Frederic Jameson, Julia Kristeva, B. Ruby Rich, Peter Wollen and Rainer herself — the film veers from one-liners to lengthy arguments, at shrink sessions and a party, and on the phone. At the shrink sessions, where the therapist (such as Deller’s ex) is never seen, Deller sits next to a sort of dream screen where clips from various films -– mainly Forties Hollywood melodramas in which Bette Davis or Barbara Stanwyck describe their abject helplessness and/or worthlessness to their men — satirically underline Deller’s confident ruminations about women.

Constantly twisting and reshaping her own material, Rainer turns Deller’s classroom lecture on Foucault into a remarkable set-piece. As Deller drones on about power, his voice adopts an echo, is mechanically sped up, and becomes isolated from other noises in the room as lengthy, sensual camera movements explore the surrounding spaces — a kitchen and bath which reveal the loft as a dwelling, students and props which periodically shift the positions. With everything in flux, Deller’s patter becomes only one element in a kaleidoscopic dance of shifting relations.

Later, we encounter Deller’s seductions of a teaching

assistant and French journalist, accompanied by

further stages of his argument. But to my mind, the

film’s emotional center gravitates around public and

political material more than the private and personal

narrative underpinning it. This includes documentary

footage about two political demonstrations by New

York artists (pointedly juxtaposed) and detailed

analyses by several observers of a layout of magazine

pages and photos — most memorably, an impassioned,

angry feminist response by artist Martha Rosler.

Where these passages differ most strikingly from

Rainer’s earlier films is in their frontal assault, conveying

some of the immediacy of a newspaper and the volatility

of agit-prop. In Rainer’s previous four features, politics

are also present, but usually folded into so many

distancing devices that they mainly come out dressed in

quotes. Here Rainer allows the politics to speak more

directly and eloquently, and it charges the rest of her

film like a live wire. Rightly assuming that we could all

use a few jolts, The Man Who Envied Women

brings our sense of the present vividly back to life.