From the Chicago Reader (December 2, 2005). Also reprinted in my collection Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia. — J.R.

This weekend the Gene Siskel Film Center launches “Merry Marilyn!,” a Marilyn Monroe retrospective, starting with two pivotal Howard Hawks features, Monkey Business (1952) and Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953). The series will include most of her major films at Fox as well as Some Like It Hot (1959) and The Misfits (1960).

By coincidence Playboy this month is publishing a package of stories about her final days and death. The magazine is reviving the popular conspiracy theory that Monroe’s reported suicide in August 1962 was murder, the consequence of her secret affairs with John and Bobby Kennedy. If, like me, you’re less interested in how she died than in how she lived, the most interesting part of this package is an inexact transcript of the freewheeling confessional tape recordings she made for her psychiatrist, Ralph Greenson, a few weeks before her death. Greenson had asked her to free-associate during their sessions, but she found that difficult. Then she discovered that she lost her inhibitions when she was by herself speaking into a recorder. Shortly after her autopsy Greenson played these tapes—once, in his office—for Los Angeles County deputy district attorney John Miner, who like him was skeptical that Monroe had been of a mind to kill herself. The transcript is only Miner’s recollection of what he heard, written hours later. It’s believed that Greenson, who died in 1979, destroyed the tapes, so this imperfect record is all we have.

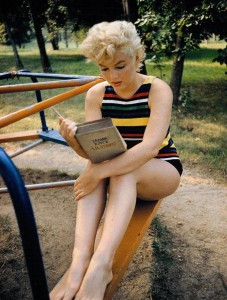

It may not be enough to prove that Monroe was murdered, but it’s more than enough to refute the condescending claims often made by would-be experts ranging from Joseph L. Mankiewicz to Clive James that Monroe was some version of the dumb blonde she was so adept at playing. James once wrote, “She was good at being inarticulatedly abstracted for the same reasons that midgets are good at being short.” Among the more intriguing sections of the transcript are her citations from and sophisticated discussion of Freud’s Introductory Lectures, James Joyce’s Ulysses, Shakespeare, and William Congreve and her persuasive critique of The Misfits: “Arthur [Miller] didn’t know film or how to write for it. The Misfits was not a great film, because it wasn’t a great script.” There are also candid remarks about her feelings for both Kennedys, her recently acquired ability to have orgasms, a brief sexual encounter with Joan Crawford, and a preoccupation with enemas tied to her problems with constipation.

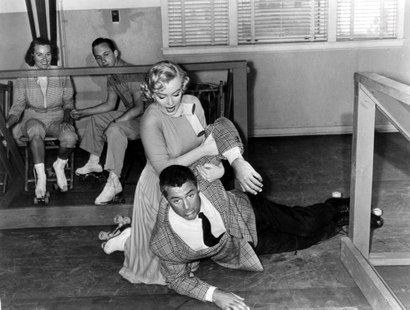

The intelligence that shines through this document can also be seen in most of her best performances, especially in the way she subtly subverted the sexist content of her material. Her brainless secretary in the otherwise brilliant Monkey Business—a relentless mockery of the cult of youth—is a notable exception, but it was made before she became a star. In her next film, the 1953 Niagara (also in the retrospective), she played her only noir heroine, and it’s one of her less distinctive performances, perhaps because the script gives her so little elbow room. But then she costarred in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, and it became easier for her to choose and inflect her roles.

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes—supposedly her most sexist film, and the one in which her character is supposedly the most brainless—isn’t nearly as simpleminded as it may at first appear. The conniving strategies of Monroe’s Lorelei Lee and her insatiable will to power as expressed through her lust for jewels —always lurking behind the dumb act and baby talk, which further infantilize her already infantile fiance, played by Tommy Noonan—are also a parodic expose of capitalist duplicity. In this respect, Monroe’s double-edged performance recalls Charlie Chaplin’s Brechtian depiction of Monsieur Verdoux—based on the notorious French Bluebeard Landru—five years earlier. Like nearly all of Verdoux’s female victims, the male targets of Lorelei’s artillery aren’t merely unattractive but grotesque—thereby implicating the spectator, who’s much more likely to identify with the predator than with the victims. (The most prominent of Lorelei’s victims, a bumbling, patriarchal fool played by Charles Coburn, is aptly nicknamed Piggy.) In all her films after Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, Monroe’s Betty Boop-ish persona is similarly complicated.

Generally speaking, during the first half of the 50s Monroe concentrated on lost-little-girl figures, starting with her gangster’s moll in The Asphalt Jungle. Variations on this role can be seen in Clash by Night, Don’t Bother to Knock (in which she plays a psychotic babysitter, perhaps the part that most evokes her troubled childhood—see below), Monkey Business, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (in which she only pretends to be vulnerable and naive), How to Marry a Millionaire (in which her determination not to wear glasses makes her look literally lost much of the time), There’s No Business Like Show Business, and The Seven Year Itch (in which she’s still a little girl, but not so lost and much more generous). After a stint with the Actors Studio, her characters tended to become more maternal as well as more ethically grounded, as in Bus Stop, Some Like It Hot, Let’s Make Love, and The Misfits. In both phases she was playing role models who represented the kind of ideal family she never had. In the underrated 1960 musical Let’s Make Love her Greenwich Village chorine, by no means brainless, is more striking for her sense of fairness and her loyalty to her coworkers than for her gullibility.

The difficulty some people have discerning Monroe’s intelligence as an actress seems rooted in the ideology of a repressive era, when superfeminine women weren’t supposed to be smart. They often fail to see past the sexist cliches she used as armor, satirically and otherwise, fail to notice that she was also positing a utopian view of sex, one that was relatively guilt free and blissfully pleasure oriented — something entirely new for that period.

Like the hard-nosed Lorelei Lee — who was perfectly capable of acting like a smart grown-up when it came to her friendship with Dorothy (Jane Russell) — Monroe had discovered early on that her greatest power rested in her capacity to look and sound innocent, hapless, and helpless. A telling anecdote was recorded by a friend of hers, gossip columnist James Bacon, about the shooting of Fritz Lang’s 1952 Clash by Night, before she became a star: “I watched Marilyn spoil 27 takes of a scene one day. She had only one line, but before she could deliver it about 20 other actors had to go through a whole series of intricate movements on a boat. Everybody was letter perfect in every take, but Marilyn could not remember that one line. . . . Finally she got it right and Fritz yelled: ‘Thank God. Print it.’ Later, in her dressing room, Marilyn confessed that she had muffed the line on purpose for all those takes: ‘I just didn’t like the way the scene was going. When I liked it, I said the line perfectly.'”

It’s the kind of negative power she still seems to have been using at the very end of her career, when her absences and delays on the never-finished Something’s Got to Give got her fired. Having seen the surviving fragments of that horrendous comedy (in the 2001 Marilyn Monroe: The Final Days), I can understand why she didn’t want to work on it, but in the end combating the studio’s tyranny with a tyranny of her own was a losing proposition. Yet she’s still the best thing in this footage. Her scenes with some children tap into her maternal instincts, and she comes to life, displaying the creative intelligence and ethical grounding of her very best work.