From the Chicago Reader (July 23, 1993). — J.R.

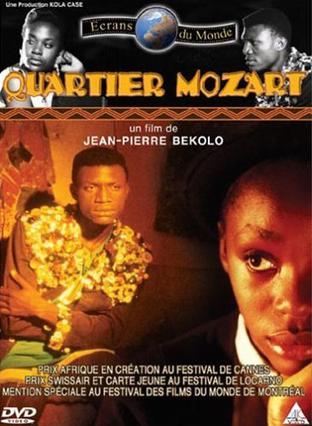

MOZART QUARTER

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Jean-Pierre Bekolo

With Serge Amougou, Sandrine Ola’a, Jimmy Biyong, Essindi Mindja, Atebass, and Timoleon Boyongueno.

I cannot tell a lie. I couldn’t follow all the plot details of Mozart Quarter — Jean-Pierre Bekolo’s delightful comic fantasy about contemporary sex relations in a working-class neighborhood in Yaounde, Cameroon — even after I saw it a third time. Some of my confusion was probably due to the subtitler’s effort to render part of the French African dialogue in American inner-city slang — an understandable goal, but one that sometimes sacrifices lucidity for superficial familiarity and occasionally produces outright gibberish. Another problem is that certain Western cultural artifacts have meanings specific to the oral story-telling culture out of which Mozart Quarter arises.

Yet this wasn’t an obstacle to my enjoyment of the film, which is playing five times this week at the Film Center; on the contrary, it operated more as an incentive. If the common liberal error in understanding non-Western societies is to assume they’re exactly like us and the common conservative error is to assume they’re nothing like us, any movie that confounds both sides is bound to have a few things to teach us.

The 26-year-old Bekolo — a veteran of Cameroonian and French television who has edited music videos with African musicians — cites as two of his main inspirations for making Mozart Quarter Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing, which he saw in Paris while taking a screen-writing course with French film theorist Christian Metz, and Lee’s book Inside Guerilla Filmmaking. Shot for only $30,000 in the neighborhood where Bekolo was born and grew up, his picture is remarkably slick and quite modern in style — the influence of Lee is everywhere — but its content and overall thrust is something else. To call it an African equivalent of She’s Gotta Have It makes sense only if one also acknowledges that it has elements Spike Lee — and American filmmakers in general — knows next to nothing about.

“I’ve tried to make a popular film where people can see themselves and be amused,” Bekolo has said. “I cast Africans belonging to a generation that grew up with television — Dallas, Dynasty, and videocassettes. The film describes an Africa that has appropriated Western culture, hence the title.” This appropriation entails not only a wonderful sound track of pulsing Afro-pop and two local women comparing the sexual attractions of Michael Jackson and Denzel Washington, but also an opening sequence that introduces seven of the leading characters — each standing on a dirt road and addressing the camera in turn as it glides past — which evokes Spike Lee’s jazzy manner.

Starting a movie with cameos of the leading characters can also be traced back to the early silent serials of Louis Feuillade, but the terse self-descriptions make it feel more contemporary, more local: many of these characters are explicitly addressing us as neighbors. Samedi (or “Saturday,” the teenage heroine played by Sandrine Ola’a) says, “I’m cool with the neighbors. Me locked up at home, why? Call me Queen of the Hood.” Then Atango (Essindi Mindja), a haberdasher and ladykiller nicknamed Young Ladies’ Candy, introduces himself: “Sorbonne graduate. Women loves clothes. I wait at my place to do inventory.” My Guy (Serge Amougou), another local stud, says, “A boy died the day he was born. My Guy. You’re a man, right? We’ll see who’s who.”

Special Correspondent — the brother of Samedi and son of Mad Dog, the local police chief — reminds us that he runs “your” errands and has a file on “you.” A female friend of Samedi’s declares, “If you only think, you’ll never act [the subtitle says ‘do’ instead of ‘act’]. Samedi does, then whatever will be, will be.” Good For Is Dead (Timoleon Boyongueno), a merchant and tightwad, informs us, “Because you’re a brother, you want credit.” And Mad Dog (Jimmy Biyong), the corrupt police chief and all-around meddler in local affairs, asks and answers his own question: “You know what Mad Dog is around here? Mad Dog is my combat name.”

Shortly afterward, various characters are seen addressing Samedi; then Bekolo himself, functioning as informal tour guide, appears on the sound track: “She’s Queen of the Hood. Stuck up — like a girl who’s never known men.” A bit later, after we see Samedi sitting next to Maman Thekla, a local witch, Bekolo adds: “In neighborhoods like Mozart, people often talk witchcraft.”

When Samedi asks the witch whether she’d rather be a man or woman, Maman Thekla replies, “A woman, but in the body of a man.” She enables Samedi to magically spy on a couple in the neighborhood before performing a more consequential piece of magic — periodically getting Samedi to enter the body of My Guy so she’ll understand better how the local studs operate. A little later Maman Thekla herself enters the body of Panka, another male local — actually a comic figure in Cameroonian folklore who can make a man’s penis disappear by shaking his hand (“It’s the only way to erase their pride,” she explains) — and is promptly hired by Mad Dog to guard his house. By the end of the story Samedi has been sexually initiated by My Guy — who “wins” the right to go after her in a checkers match — but only after he, being possessed by Samedi’s spirit, suffers impotence on his first try.

Not knowing to what extent a belief in witchcraft functions meaningfully in contemporary Cameroon, I can’t comment on the precise levels of irony intended here, though the playful feeling of the movie throughout suggests that Bekolo is incorporating witchcraft in his plot mainly to say certain things about Cameroonian sexual politics. His main target is machismo (or what the Film Center Gazette calls “male machismo,” presumably to distinguish it from female and neuter machismo). We see it manifested not only in competitive male courting rituals, complete with braggadocio and trade-offs, but also in the comically tyrannical behavior of Mad Dog toward his first wife (whom he tries to get rid of to make room for a younger woman) and the community at large.

Perhaps significantly, the only two characters with a close relationship to technology are this bumbling police officer, who barks commands into an omnipresent walkie-talkie and becomes hysterical when his TV’s stolen, and his chum the local priest — another comic villain, who obligingly comes over to bless the officer’s house after the new wife is installed — who’s first seen opposite a computer in his own office. (At another point Mad Dog seems to be equated directly with Danny Aiello’s Sal in Do the Right Thing, when he orders the loud music in a bar turned down.)

Bekolo also has a lot of fun charting local gossip — the clearest indication of his debt to an oral tradition –a mong males and females alike. Various neighborhood busybodies often serve expository and choral functions rather like those of the townspeople at the beginning of Welles’s The Magnificent Ambersons, and their interest in and amusement at what’s going on prove to be infectious; the movie often orchestrates their commentaries like riffs.

Stylistically, Bekolo shows his inventiveness in a number of ways — with syncopated jump cuts timed to rhythmic chants on the sound track, with characters addressing the camera (two studs amiably defer to each other as “boss,” then ask the viewer to arbitrate), and with a sequence of black-and-white stills in which characters speak in comic-strip bubbles, aping the Italian fumetti. It’s an eclecticism that again suggests the influence of Spike Lee, but it points equally to a patchwork quality in the youth culture being depicted — a sense that everyone’s swimming in the same hybrid ocean, the same pop surf that allows Mozart Quarter to find its way to us.