From the November 29, 1990 Chicago Reader, where some wag had the bright idea of calling this piece “The Stinging Nun”. — J.R.

THE NUN

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Jacques Rivette

Written by Jean Gruault and Rivette

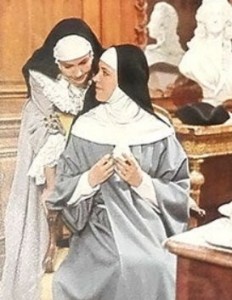

With Anna Karina, Liselotte Pulver, Micheline Presle, Christianne Lenier, Jean Martin, and Francisco Rabal.

While it’s certainly regrettable that it’s taken Jacques Rivette’s controversial second feature 24 years to get distributed in this country in its complete and original form, there’s also something felicitous about its finally becoming available in an era when censorship of the arts is again on the warpath. Delays of various kinds have been central to the history of this potent if surprisingly chaste film, and there were comparable delays between the year Denis Diderot finished the novel that the film is based on (1760) and its actual appearance in print (1780-82 in serial form, and 1796–12 years after Diderot’s death — in the first printed edition).

Oddly enough, although the film makes no mention of this, the novel started out as a practical joke — an elaborate hoax staged by Diderot and some of his friends, who wanted to lure one of their cronies, the Marquis de Croismare, back to Paris after he retired to Normandy in 1758. A pious Christian (unlike many of the other Encyclopedists in Diderot’s circle), Croismare had been moved by the plight of Suzanne Simonin, a young nun who was sent to the convent of Longchamp against her will by her parents and who had been trying, through legal means, to get released from her vows. Although Croismare didn’t even know her name or the merits of her individual case, he pleaded on her behalf to the court, but she wound up losing her case anyway.

Exploiting Croismare’s distress over this young woman, Diderot and his friends drafted fictional letters from her to Croismare, pretending that she had escaped from the convent, was staying incognito at the home of Madame Moreau-Madin (a real person, who received and passed along Croismare’s replies without knowing anything about the hoax), and was in desperate need of Croismare’s protection. Croismare fell for the hoax, but the plot backfired: instead of coming to Paris, he offered other forms of assistance, including employment at his own chateau. In desperation, Diderot and his friends finally forged letters from Madame Moreau-Madin, explaining that the former nun was now too ill to travel. Croismare only discovered that the whole episode was contrived when he met Madame Moreau-Madin eight years later, and reportedly he laughed heartily about it.

But the hoax had an unexpected side effect on Diderot: in the course of writing one of the contrived letters, he became so emotionally involved in the real plight of Suzanne Simonin that the letter mutated into a first-person novel narrated by her, a polemic about the imposition of religious vows on individuals against their wills. To cinch his argument, he made his heroine neither a nonbeliever nor a libertine, but a devout and innocent virgin who wanted her freedom simply because she lacked a religious calling. And according to Richard Griffiths — whose introduction and afterword to the Signet edition of the novel is the source of all this background –Diderot became so passionate about the issue that he continued to revise the book over the remaining 20-odd years of his life, gradually transforming it from an attack on the monastic system to a philosophical inquiry into the matter of freedom in general. Today, it is rightly regarded as one of his masterpieces, and one of the greatest of all French novels.

Masterpiece or not, the book wound up on the Catholic church’s condemned list for both its polemics and its scandalous (if authentic) account of certain kinds of behavior, sexual and otherwise, that went on in convents. When Rivette first proposed making a film of the novel in 1962, roughly two centuries after it was written, his initial script was rejected by a French governmental committee and had to be rewritten three times over the next three years — with the title lengthened to Suzanne Simonin, la religieuse de Denis Diderot and a disclaimer added by the film’s producer explaining that it was a work of fiction — before shooting was allowed to begin. In the meantime, with financial backing from Jean-Luc Godard, Rivette had directed a stage adaptation of the novel in Paris, with Anna Karina — Godard’s principal leading lady and wife at the time — in the role of Suzanne.

By the time the film, which also starred Karina, was completed in early 1966, a massive national campaign had already been waged against it in France. Petitions were circulated, and many children at Catholic schools were ordered to write out dictated letters attacking the still-unfinished film that were then signed by their parents and mailed to de Gaulle’s minister of information, Yvon Bourges. Despite these efforts, the censors passed the completed film; and when Bourges asked the board to see the film again and reconsider its decision a week later, they passed the film again — this time restricting it to spectators over 18 and recommending that the film not be exported to any of the French colonies (where the natives, it was felt, might be confused into believing that the film was implying something about modern French nuns). Nevertheless, two days later Bourges took the unprecedented step of overruling his own board’s decision and banning the film completely, both in France and for export — creating a nationwide uproar that lasted more than a year. In fact, it wasn’t until Bourges was succeeded in his position by Georges Gorse in 1967 that the film was finally passed.

A few years after The Nun received its U.S. premiere at the New York film festival, it was picked up by a distributor who decided to “improve” the film by recutting parts of it and eliminating roughly 15 minutes. Ironically, the film was promoted at the time by both the distributor and critics as a famous banned work finally available to American audiences, with no mention made anywhere of these “cosmetic” changes. (The same policy remains standard practice today; practically no U.S. critics bothered to call attention to the substantial revisions made in The Little Thief and Cinema Paradiso when those movies were released over here.) So it is highly fitting that the complete original version of Rivette’s film is finally arriving at the same time that Jesse Helms and his ilk are trying to keep us confined in monastic institutions of their own making.

It isn’t only because of the timeliness of its theme that The Nun seems better every time I see it. The film is generally described as the only “classical” (read “conventional”) narrative film of a modernist filmmaker, and I suppose from some points of view it is; but those points of view all tend to exclude much of what remains exciting, rich, and daring about Rivette’s masterpiece. Agreed, it tells a story in strict linear fashion, beginning in Paris in 1757 and ending in Paris three years later, with little ambiguity about what happens in between. But to understand what the film is doing, I think one has to see it as a dialectic — between classicism and modernism, past and present, outside and inside, freedom and confinement, decoupage (a relatively predetermined, rigidified form) and mise en scene (a relatively dynamic, variable form).

Let’s start with the sound track, which is probably the film’s most original feature and its most conspicuously neglected. Influenced by the musical theories of composer Pierre Boulez, Rivette conceived of each shot in the film as an individual “cell,” roughly analogous to the musical “cell” in Boulez’s notion of “cellular” composition. As Rivette described it in an interview, “The idea was that each shot had its own duration, its tempo, its ‘color’ (that is, its tone), its intensity, and its level of play. . . . The original idea of La religieuse was a play on words: making a ‘cellular’ film, because it was about cells full of nuns.” Time and budget restrictions prevented him from realizing this project as fully as he’d hoped, but the cellular form is certainly evident in Jean-Claude Eloy’s percussive contemporary score — a striking aural tapestry of music, silence, and both natural and artificially created sound effects, parsed out in relation to individual shots and sequences.

The film is built around a climactic, extended musical passage accompanying a lengthy scene near the end. In this scene — which occurs between Suzanne and Dom Morel (Francisco Rabal), her confessor and the alienated priest who later masterminds their escape from the convent — Suzanne finally comes to an important realization about her situation, and the musical passage reassembles the various musical fragments of the preceding two hours like the pieces in a jigsaw puzzle, giving the preceding events a more discernible shape.

More generally, the principal sound effects in the film — church bells, wind, thunder, rain, crickets, roosters and other birds — serve to embellish the scenes, especially those in interiors, with constant material reminders of the world outside, just as Eloy’s musical passages often externalize emotions that convent life tends to keep under wraps. The sound track frequently forms a dialectic with the images of the two convents — images dominated by oppressive, metallic colors — suggesting both physical and emotional space beyond Suzanne’s confinement.

There’s an equally important dialectic in the story itself, between the two convents Suzanne is sent to. The first, Longchamp, is austere, repressed, and punitive, its grim rigors made bearable for Suzanne only by the kindness of Madame de Moni (Micheline Presle), the mother superior who befriends her. After Madame de Moni’s death, Suzanne is perceived as a threat to the convent’s tranquillity, and the new mother superior persecutes her endlessly, which leads to Suzanne’s legal efforts to have her forced vows rescinded.

When she finally gets transferred to the more worldly and progressive Arpajon convent — a transition beautifully conveyed in a sudden exterior shot of three nuns peering out separate windows at Suzanne’s offscreen arrival, followed by a downward pan to a fourth nun coming out the front door to greet her — the atmosphere quickly turns airy, giddy, and playful; the movements of both the characters and the camera are much brisker in this section and a sense of the outdoors much more prominent. But when Suzanne finds herself becoming the love object of the mother superior, Madame de Chelles (Liselotte Pulver) — leading to the rejection and grief of another nun who used to be favored by her — the apparent freedom of Arpajon becomes no less tainted than the constraints at Longchamp.

In spite of the sympathetic heroism of Suzanne throughout, Rivette is as nonjudgmental toward the other characters as Diderot was. The villains in this story are institutions and social practices, even society itself, but not individuals; the film continually makes it clear that Suzanne’s oppressors are as victimized as she is. Indeed, it is precisely this detachment that makes the film so provocative and that clearly led to its initial banning; nowhere is it suggested that Suzanne’s plight would improve if the church merely got rid of a few bad apples. If there are bad apples, they are the institutional powers themselves.

The dialectic between Longchamp and Arpajon also suggests a certain historical dimension. As critic Elliott Stein wrote in 1966, “When religious life is not the result of spontaneous engagement, it can lead to depravity; the Ancien Regime, in encouraging such practices, planted the seeds of its own destruction.” The repression and sadism of Longchamp and the worldliness and amour fou of Arpajon are two sides of the same coin. Similarly, outside convent life, Suzanne can exist only as an object of economic exchange or as a scapegoat for guilt and corruption. She is initially forced to become a nun because of her beauty (which threatens the courtship and possible marriage of an older sister), her secret illegitimacy (her presence constantly reminds her mother of the adulterous affair that produced her), and her family’s economic worries. When she finally escapes from Arpajon, the only role that society offers her is that of a prostitute, the world of licentiousness no more than a macabre parody of the world of the convent.

While many critics have compared The Nun to films by Robert Bresson and described the pacing as slow — I carelessly did the same when I first saw the film back in the 70s — these evaluations come from a superficial thematic reading of the film, which reduces its essential qualities to the sameness, slowness, and claustrophobia of convent life. In fact, the film’s style — featuring slow camera movements and occasional jump cuts within mainly very short scenes — is quite contrary to Bresson’s, and the pacing has none of the stately doggedness of Bresson’s films about confinement, such as A Man Escaped.

Rivette’s own stated directorial model was Kenji Mizoguchi, and it’s his style Rivette comes closer to — although he might come closer yet to the highly mobile, extended-take styles of both Carl Dreyer (in Day of Wrath and Ordet) and Otto Preminger, which characteristically employ mise en scene to spell out a sense of freedom within confinement. It is worth noting that Kinuyo Tanaka, the lead actress in Mizoguchi’s feminist masterpiece The Life of Oharu — the film of his that most closely resembles The Nun — subsequently became the first Japanese woman to direct films, while Anna Karina became a director in 1973, with an appealing feature (Vivre ensemble) that has regrettably never crossed the Atlantic. One would like to think that this parallel is more than just coincidental: both The Life of Oharu and The Nun are passionate protests against the enslavement and censorship of women. Karina’s remarkable performance in The Nun — surely her most powerful to date –has little in common with her star turns in Godard’s pictures, where her femininity is generally celebrated with a certain condescension.

In the final analysis, whether one perceives the film as slow or fast largely depends on the degree to which one perceives the mise en scene and sound track as central elements to the story. Reduced to a string of incidents, The Nun is as slow and monotonous as the convent life it partly depicts. But Rivette’s subject is not convent life; it’s the struggle of an individual life and consciousness, and as a story about that struggle the film is in constant flux.

One striking and characteristic example of this occurs in the austere church sanctuary at Longchamp when Suzanne, denounced by her offscreen mother superior as being possessed by the devil, appears to be seated alone at the end of a bench. But as a slow pan reveals an entire row of nuns seated beside her, the social dynamics of the scene undergo a profound shift. In terms of plot alone, the scene is static; but in terms of our sense of Suzanne in relation to the mother superior and to the other nuns, what we’re experiencing is highly volatile. Because the film is charting the continual struggle of a consciousness toward freedom and against a society that blocks this freedom at every turn, the overall effect of this grim story is ultimately exalting rather than depressing — and tragic rather than simply melodramatic. Surely that it is why it was banned a quarter of a century ago and why it continues to stir lethal thoughts and dangerous feelings today.