From Monthly Film Bulletin, December 1984 (Vol. 51, No. 611). In retrospect, I’m rather proud of the synopsis here, which must have been a bitch to put together. -– J.R.

Colloque de chiens (Dogs’ Dialogue)

France, 1977

Director: Râúl Ruiz

Cert–AA. dist–BFI. p.c–Filmoblic/L’Office de la Création Cinématographique. p–Hubert Niogret. asst. d–Michel Such. sc–Nicole Muchnik, Raul Ruiz. ph—Denis Lenoir, Patrice Millet. In colour. still ph–Patrice Morère, Mario Muchnik. ed–Valeria Sarmiento. m–Sergio Arriagada. cost–Fanny Lebihan, Yves Hersen. sd. rec–Michel Villain. sd. re-rec–Paul Bertaud. English version/English commentary—Michael Graham. French version/French commentary–Robert Darmel. l.p–Eva Simonet, Silke Humel, Frank Lesne, Marie Christine Poisot, Hugo Santiago, Geneviève Such, Laurence Such, Michel Such, Pierre Olivier Such, Yves Wecker, the dogs of the Gramont refuge. 1,938 ft. 22 mins. (35 mm.)

The film alternates three kinds of material: footage of barking dogs, shots of streets and other locations, and the following story, illustrated chiefly by a series of stills (and occasionally by shots in motion) and narrated off-screen: Monique discovers in a school playground that the woman she believes to be her mother isn’t her mother. At home, she learns that her real mother is a woman named Marie, who doesn’t know who her father was. As a young woman, Monique sets off for Bordeaux to forget her past, and begins collecting lovers. On night duty at a hospital she makes love to a male patient. On Christmas eve, 1966, she meets the sixty-five-year-old Hubert (owner of an Alfa Romeo) in a nightclub, and becomes his kept mistress for a year until he grows tired of her, then becomes a street prostitute. One day she is visited by Henri, an orphan from her village, now a radio and TV repairman, who falls in love with her without knowing her profession. Monique saves enough money to take over the Joliment Café, which Henri helps her to run. Three years later, the couple, who now have a son, are visited by Monique’s friend Alice from Bordeaux, who knows about her past, and Henri falls hopelessly in love with her. On a park outing, Henri and Alice wander off together, and Monique shoots her son and herself with a single bullet from a revolver. Henri marries Alice but, becoming distraught after learning more about Monique, kills Alice with a wine bottle, chops her body into several pieces, and proceeds to bury them in different locations. He then sets off for Marseilles and a life of crime, eventually being sentenced to five years in prison for a minor offence. There he makes love to an ailing male prisoner. After his release, Henri learns that police inspector Maurice-José Morère has discovered the buried pieces of Alice by noticing on a map that they are all hidden at an equal distance from the Joliment Café, forming a circle. To disguise himself,

Henri undergoes a sex change operation and becomes Odile. On Christmas eve, 1974, she meets a sixty-five- year-old owner of an Alfa Romeo in a nightclub and becomes his kept mistress for a year until he grows tired of her, then becomes a street prostitute.

Eventually she repurchases the Joliment Café and adopts an orphan, Luigi. One night her lover from prison breaks into the café and kills her. A few days later, Luigi is told in a school playground that his mother is dead, killed by her lover, and he replies that Odile isn’t his mother.

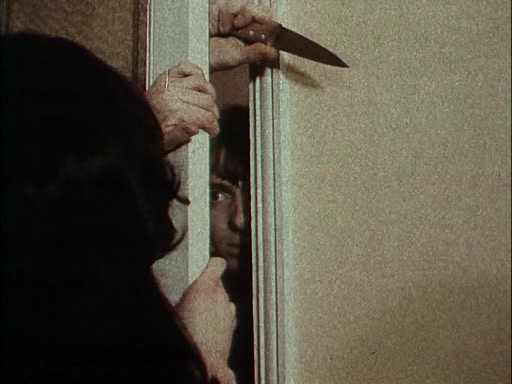

Missing from the above synopsis of the hilarious Colloque de chiens are the repetitions of certain cliché phrases in the off-screen commentary (e.g., in hospital and prison alike, “A moment later, as she/he arranges his bed, the young woman’s/man’s hands stray under the sheets….Their union is swift”), which lend an additional circularity to Râúl Ruiz’s reductio ad absurdum, run-on melodramatic plot. The principle of overload even infects the stills which illustrate the ‘climactic’ episode, the killing of Odile: alternate shots show her assailant grasping either a knife or a bottle, as if to over-determine further an already ludicrously overdetermined chronicle of woe. While the barking dogs and location shots are clearly less integrated, they are useful for precisely that reason: as breathing spaces in the cancerous narrative proliferation, hence as moments of relative sanity and repose.

Virtually all Ruiz’s films have certain academic aspects –- effects that seem studied rather than stumbled upon. The most studied element here is the deliberate naivety of the narrative voice (ably conveyed by Michael Graham’s dry, deadpan delivery), a parodic exposition of the rhetoric of melodrama which accommodates all possible forms of crisis within its measured, monotonous cadences — an anonymous register of outrages that seems to take excess as a matter of course. In contrast to this consistency is the more lackadaisical progress of the plot itself, which blithely leaps from Monique as schoolgirl to Monique as young woman without even a hint of ellipsis, calmly glides past the almost total lack of motivation for Henri’s murder of Alice, and no less casually heaps one improbable repetition on another to impose the desired circularity on the tortured careers of Monique and Henri.

The net result of these combined strategies is to reveal melodrama itself as a pure formal mechanism, with characters and plot reduced to the status of necessary props. The disturbing lack of individuality and identity which derives from these attitudes, turning all the characters into mere aspects of a playful, arbitrary schema, seems merely the logical outcome of Ruiz’s skepticism about the homogeneity of his own authorship.

With characters and auteur all assigned such a mockingly nihilist function, the dialogue that ensues might well signify no more than the barking of dogs.