Commissioned by Arrow Video for their box set The Rainer Werner Fassbinder Collection, vol. III, released in summer 2022. -- J.R.

“Capitalism is the plague. Criminals are its gods.” --Fassbinder during the German trailer of Gods of the Plague Rainer Werner Fassbinder was only twenty-four when he made his first four features in 1969, the third of which was Gods of the Plague. Years later, when he compiled a list of what he believed were his ten best features, Gods of the Plague made it into fifth place. The only other very early film on this list was his seventh feature, Beware of the Holy Whore — one of the six feature-length works he made in 1970 -– which figured in first place.

An inveterate list maker who plainly enjoyed that somewhat adolescent pastime, Fassbinder also ranked his ten favourite films made by others (topped by Luchino Visconti’s The Damned) and his ten favourite actresses and actors, both in the films of others and in his own films: Marilyn Monroe, Hanna Schygulla, Clark Gable, and Armin Mueller-Stahl. He also plausibly put himself at the top of his list of the ten most influential German New Wave directors.

One can argue that early Fassbinder is very much a matter of certain raw and irreducible basics – including the contradictions that would haunt the remainder of his prolific oeuvre, which ended, sadly yet predictably, with his drug-fueled death in 1982. For starters, his leftist critique of German middle-class culture was both contradicted and inflected by a highly conservative fatalism and defeatism. He seemed convinced that change was impossible, and at times even appeared to relish that fact — a sentiment already expressed in the title of his first feature, Love is Colder Than Death, which inevitably suggests the German Romantic notion that death must somehow be even warmer than love. In most of these early features, cruelty in large doses often plays out against tenderness, most often in smaller doses — though one mark of distinction in Gods of the Plague is that its doses of affection and tenderness tend to be sweeter and \ampler than what one usually expects from Fassbinder. Furthermore, heterosexual flirtation and prostitution play out against homoeroticism in these early crime pictures, and the desire for independence plays out against the brutality and seeming permanence of the System (known as the Syndicate in Love is Colder Than Death) –- as metaphorically relevant as the commercial film industry and its offshoots must have seemed to Fassbinder and his rebellious stances at the time. As Hanna Schygulla remarked in an interview, reflecting on what she thought Fassbinder wanted to accomplish in his early films, she settled on the English word “upset”: his films are indeed upsetting, not only in their design but in their delivery. Even though Marlon Brando is strangely absent from Fassbinder’s list of his favourite movie actors, one often feels that Stanley Kowalski’s comportment at the dinner table anticipates the Fassbinder style of behavior in more ways than one.

Coupled with Fassbinder’s brutality, and sometimes indistinguishable from it, are the bisexual sadomasochism and bossy power trips of the films themselves. Indeed, every scene of Beware of the Holy Whore (a film à clef about the making of Fassbinder’s Whitey in Italy only five months earlier) qualifies as some sort of power game, often coupled with angry yelling and/or violence, and inflected by a discontinuous rhythm of starting and stopping that tends to dominate the action. The line of dialogue that concludes this action, the same one that’s repeated most often in the film, is “I guess I won’t be content until I know that he’s been completely destroyed,” and the film’s closing motto, from Thomas Mann — which confirms that Fassbinder was fully aware of his own contradictions — is, “And I say to you that I am weary to death of depicting humanity without being part of humanity.”

The formally inclined critics who liked to argue that Fassbinder was the “successor” of Godard, doing for the 70s something comparable to what Godard was doing for the 60s in terms of impact, output, and influence, tended to overlook or sidestep the political implications and ramifications of his sadomasochism. Godard’s early politics were confused, to say the least, before they became doctrinaire for a spell after May 1968, but even though Godard himself would later label Breathless, his first feature, a “fascist” film, he never succumbed to the sadomasochism that turned Fassbinder’s leftist politics away from a belief in the future and towards a more fatalistic absorption in the ugly past. At best and at most, this made Fassbinder a historian. At worst it made him a cynical defeatist exulting in some form of stalemate –even though this ultimately yielded, for my taste, his most brilliant work, Martha (1973), a sarcastic black comedy about what he viewed as the sadomasochistic givens of bourgeois marriage, and a poker-faced Sirkian farce that luxuriates in its own stylistic excess. Indeed, in any tug of war between leftist politics and sadomasochism that might turn up in a Fassbinder film, it is almost invariably his grim sexual politics rather than his ethics that win the day, a kind of loving insult to the audience’s assumed respect for power over virtue.

One can argue that early Fassbinder is very much a matter of certain raw and irreducible basics – including the contradictions that would haunt the remainder of his prolific oeuvre, which ended, sadly yet predictably, with his drug-fueled death in 1982. For starters, his leftist critique of German middle-class culture was both contradicted and inflected by a highly conservative fatalism and defeatism. He seemed convinced that change was impossible, and at times even appeared to relish that fact — a sentiment already expressed in the title of his first feature, Love is Colder Than Death, which inevitably suggests the German Romantic notion that death must somehow be even warmer than love. In most of these early features, cruelty in large doses often plays out against tenderness, most often in smaller doses — though one mark of distinction in Gods of the Plague is that its doses of affection and tenderness tend to be sweeter and \ampler than what one usually expects from Fassbinder. Furthermore, heterosexual flirtation and prostitution play out against homoeroticism in these early crime pictures, and the desire for independence plays out against the brutality and seeming permanence of the System (known as the Syndicate in Love is Colder Than Death) –- as metaphorically relevant as the commercial film industry and its offshoots must have seemed to Fassbinder and his rebellious stances at the time. As Hanna Schygulla remarked in an interview, reflecting on what she thought Fassbinder wanted to accomplish in his early films, she settled on the English word “upset”: his films are indeed upsetting, not only in their design but in their delivery. Even though Marlon Brando is strangely absent from Fassbinder’s list of his favourite movie actors, one often feels that Stanley Kowalski’s comportment at the dinner table anticipates the Fassbinder style of behavior in more ways than one.

Coupled with Fassbinder’s brutality, and sometimes indistinguishable from it, are the bisexual sadomasochism and bossy power trips of the films themselves. Indeed, every scene of Beware of the Holy Whore (a film à clef about the making of Fassbinder’s Whitey in Italy only five months earlier) qualifies as some sort of power game, often coupled with angry yelling and/or violence, and inflected by a discontinuous rhythm of starting and stopping that tends to dominate the action. The line of dialogue that concludes this action, the same one that’s repeated most often in the film, is “I guess I won’t be content until I know that he’s been completely destroyed,” and the film’s closing motto, from Thomas Mann — which confirms that Fassbinder was fully aware of his own contradictions — is, “And I say to you that I am weary to death of depicting humanity without being part of humanity.”

The formally inclined critics who liked to argue that Fassbinder was the “successor” of Godard, doing for the 70s something comparable to what Godard was doing for the 60s in terms of impact, output, and influence, tended to overlook or sidestep the political implications and ramifications of his sadomasochism. Godard’s early politics were confused, to say the least, before they became doctrinaire for a spell after May 1968, but even though Godard himself would later label Breathless, his first feature, a “fascist” film, he never succumbed to the sadomasochism that turned Fassbinder’s leftist politics away from a belief in the future and towards a more fatalistic absorption in the ugly past. At best and at most, this made Fassbinder a historian. At worst it made him a cynical defeatist exulting in some form of stalemate –even though this ultimately yielded, for my taste, his most brilliant work, Martha (1973), a sarcastic black comedy about what he viewed as the sadomasochistic givens of bourgeois marriage, and a poker-faced Sirkian farce that luxuriates in its own stylistic excess. Indeed, in any tug of war between leftist politics and sadomasochism that might turn up in a Fassbinder film, it is almost invariably his grim sexual politics rather than his ethics that win the day, a kind of loving insult to the audience’s assumed respect for power over virtue.

As French critic Luc Moullet has suggested while writing about such right-wing entertainments as King Vidor’s The Fountainhead and Howard Hughes and Josef von Sternberg’s even campier Jet Pilot, conservative movies, thanks in part to their contempt for collectivity and their preference for individual fulfillment, tend to be sexier than their leftist equivalents. Moreover, one could argue that sex seen as painful domination and submission provides a juicier spectacle than most forms of leftist exaltation.

The fact that Fassbinder’s favourite among his own works was his most intertextual exposure of his own practice, in Beware of a Holy Whore, only emphasizes the self-referential nature of his work as a whole, and also the intertextuality of the subsequent work by by others that it would inspire. For his own work, consider the fact that Franz Walsch, the full name of Fassbinder’s hero in Love is Colder Than Death and Gods of the Plague (and also a less prominent character in his 1970 The American Soldier, played once again by the writer- director) served as Fassbinder’s pseudonym for his work as an editor. The eponymous hero of The American Soldier spells out this name as follows, in another Fassbinderian list that seems to illustrate some of the writer-director’s predilections: “W as in war, A as in Alamo, L as in Lenin, S as in science fiction, C as in crime, and H as in Hell.”

In the same film, as if to cinch Fassbinder’s identification with the character, his own mother plays the character’s mother, Mrs. Walsch. (One wonders if the surname might have been inspired by Raoul Walsh, whose The Naked and the Dead was listed as his second favourite film after Visconti’s The Damned, just ahead of Lola Montez.) At one point in Gods of the Plague, Franz Walsch identifies himself as “Franz Biberkopf,” thus looking ahead towards his 1979-1980 adaptation for German television of what may have been his favourite novel, Alfred Doblin’s doom-laden 1929 Berlin Alexanderplatz. Regarding the films of others, consider that Lou Castel, who plays the director in Beware of the Holy Whore, will also play the director who replaces Jean-Pierre Léaud in Olivier Assayas’ Irma Vep, over a quarter of a century later.

As Thomas Elsaesser pointed out, “Gods of the Plague is both a variation on and a sequel to Love is Colder Than Death”. (In between came his early masterpiece, Katzelmacher, at once Chabrolian and Warholian in its sardonic relish for its portraiture of the bad behavior of its lower-middle-class workers.) In both films, all the major male characters are either gangsters or cops and most of the women are prostitutes, with a key difference that Franz, the gangster played by Fassbinder in the first film, is replaced by Harry Baer in second. (The fact that Fassbinder had no acting part undoubtedly gave him more time to focus on the mise en scene and the compositions, which are far more developed and intricate.) Hanna Schygulla again plays Johanna, Franz’s girlfriend, whom he soon abandons for Margarethe (played by future filmmaker Margarethe von Trotta), and there’s the crucial addition of another male love object, Günther Kauffmann as Günther, another gangster buddy of Franz, despite the fact that he has killed Franz’s brother Marian (Marian Seidowski). Kauffmann (1947-2012) was an actor whom the director was romantically and sexually obsessed with at the time; he had already appeared in The American Soldier, Whitey, and Baal at this point, and would go on to appear in many more films afterwards, mostly in Germany, including quite a few of Fassbinder’s.

The main influence on both Love is Colder Than Death and Gods of the Plague is probably Godard’s films with gangsters (Breathless, Vivre Sa Vie, Band of Outsiders), although Jean-Pierre Melville’s more meditative and minimalist films about gangsters, influenced by American film noir (which also informed Godard’s gangster movies), also play a significant role. (The female betrayals to the police in both Fassbinder films seem directly traceable to Breathless.)

Love is Colder Than Death is dedicated to Claude Chabrol and Eric Rohmer (the two most politically and formally conservative of the French New Wave directors), Jean-Marie Straub (from whom Fassbinder borrowed a lengthy shot in The Bridegroom, The Comedienne, and the Pimp showing street prostitutes in Munich, to which he added guitar music), and “Linio and Concho” (the names of two characters in Damiano Damiani’s 1967 A Bullet for the General, an Italian western with Mexican gunrunners).

The Bridegroom, the Comedienne, and the Pimp, a singular short film made up of many seemingly disjointed segments but only 12 shots, uses such sources as poetry by Saint John of the Cross, passages from Bach’s Ascension Oratorio, and a performance of Ferdinand Bruckner’s 1926 play Pains of Youth, which Straub reduced to only 11 minutes, recording it in a single take from a fixed camera. (Fassbinder stars as a pimp; he turns up again at the very end of the film, when his character is shot dead by the heroine.). This version of the play was also performed live at Munich’s Action-teater, on a program with Fassbinder’s first play, which became the source of his second feature, Katzelmacher (in which Fassbinder also stars). A radical concentration and organization of the Bruckner play clearly had a lasting effect on Fassbinder’s work. When the Action-Theater was disbanded in May 1968 — reportedly after one of its founders, jealous of Fassbinder’s growing influence in the group, trashed the premises — it was immediately reformed under Fassbinder’s full control and renamed the Anti-Theater. By most accounts, including Fassbinder’s, his first nine features up through Beware of a Holy Whore were Anti-Theater productions — in much the same way that Orson Welles’s early stage and radio work and films were all Mercury productions – and the stage set seen in Straub’s short is also visibly used in Love is Colder Than Death.

Gods of the Plague, far less theatrical in its staging than Love is Colder Than Death, with striking uses of deep focus and tilted camera angles, is a noticeable improvement in many respects. The fact that the budget of DEM 180,000 was roughly twice as much as what he had for his two previous features can be felt as well as heard and seen: even Hanna as a character has clearly moved up the economic ladder. And Harry Baer as a much more attractive Franz Walsch than Fassbinder was himself, comparable to Lou Castel playing Fassbinder in Beware of the Holy Whore, is another kind of upgrade that affects everything else.

Although the film references tend to be far more overt (Franz, released from prison, finds Johanna in a feathery dress, lip-syncing a Marlene Dietrich song for her male customers in a ritzy nightclub known as the Lola Montez, and a still of Dietrich in Josef von Sternberg’s The Devil is a Woman decorates her dressing room), the plot has fewer gratuitous murders and registers much less like a ponderous and diffident stylistic exercise. As Michael Koresky aptly observed, Love is Colder Than Death never allowed us to identify with or care about any of its characters, gangsters or victims: “They are like mannequins, posed in static tableaux, often in stark, white rooms.” This time we’re given more opportunities to react to them less clinically.

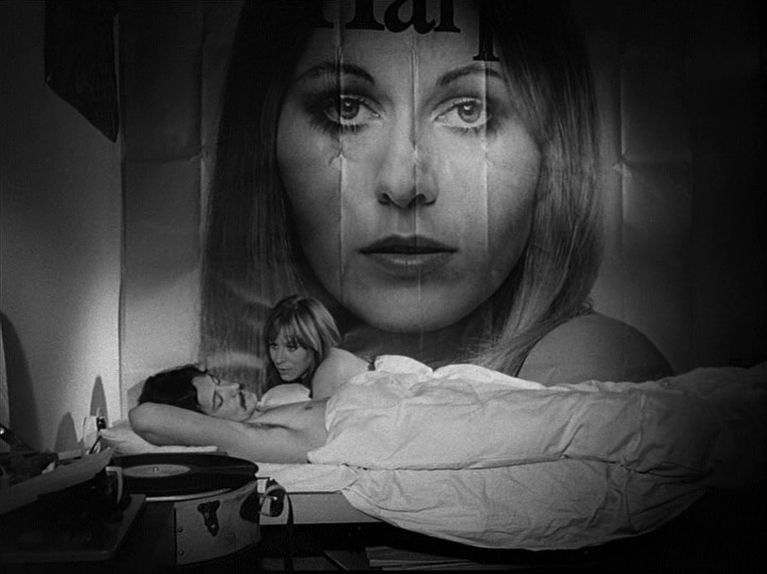

Koresky’s notes on the sequel/remake seem equally appropriate: “Gods of the Plague is a beautiful, even tender, film. There is a newfound adventurousness to Fassbinder’s visuals, including tracking shots and zooms; an elegant employment of multiple planes within frames; and an expressive use of mirrors and set design. All of this fluidity, however, is in the service of another study in inertia; Gods of the Plague ultimately illustrates the futility of romance and the inevitability and ignominy of death.” Ending with a bloodbath in a supermarket only makes the ignominy more apparent.

Johanna’s first encounter with Franz is seen in her dressing-room mirror, and their drive to a classy restaurant shows a mastery of high-contrast noir lighting that suggests emulation rather than crude imitation. Fassbinder insisted in his interviews about not having wanted to parody his model — an impression possibly left by some of his faltering techniques, such as the over-recording of many of the sound effects in Love is Colder Than Death (e.g., page-turning and footsteps). But Schygulla has noted that the key lesson she learned from Fassbinder’s practice and example was that ignorance and an inability to do certain things made it possible to learn how to accomplish other things. Fassbinder’s singular cinema was clearly one of them.