From Monthly Film Bulletin, January 1976. — J.R.

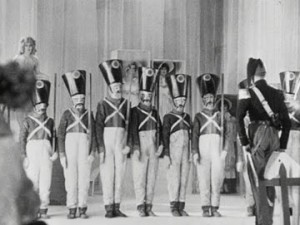

Prividenie, Kotoroe ne Vozvrashchaetsya

(The Ghost that Never Returns)

U.S.S.R., 1929

Director: Abram Room

In an unidentified South American country, José Real is serving a life sentence for having led an oilfield workers’ strike ten years earlier. After another prisoner breaks away from guards to tell him that the prison governor has a letter from his wife, and then leaps to his death, Real leads a revolt among the prisoners. The governor orders that they be sprayed with hoses; the revolt subsides, and Real is locked into a narrow cupboard. Conferring with the chief of the secret service, the governor recalls the regulation whereby a prisoner who has served ten years is entitled to one day’s liberty and decides to grant this to Real, with the understanding that he will be killed at the day’s end for trying to ‘escape’. After being shown his wife’s letter and hearing from a newly arrived prisoner that a new strike is planned at Hillside Well, Real agrees to go. Five days later – after news of his imminent arrival has reached his family, their neighbors and the oilfield workers — he sets out, warned that no one who has taken this leave has ever made it back alive. Read more

From Film Society Review (Vol. 4, No. 5, January 1969) — the first magazine, apart from school and college publications, where I ever published film criticism, for a total of three issues. This was my third and final piece for them. — J.R.

Jon Rosenbaum

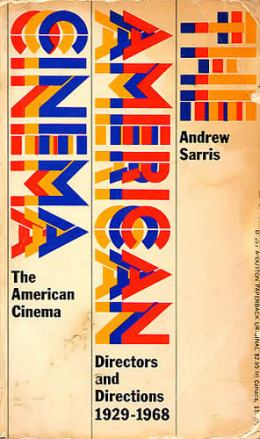

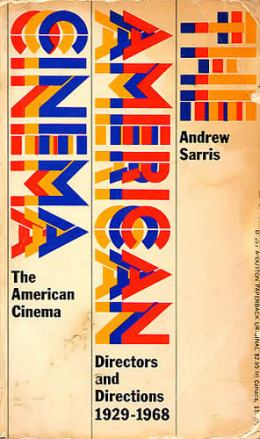

THE AMERICAN CINEMA: DIRECTORS AND DIRECTIONS 1929-1968, by Andrew Sarris, New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1968. 383 pp. $7.95, $2.95 (paperback).

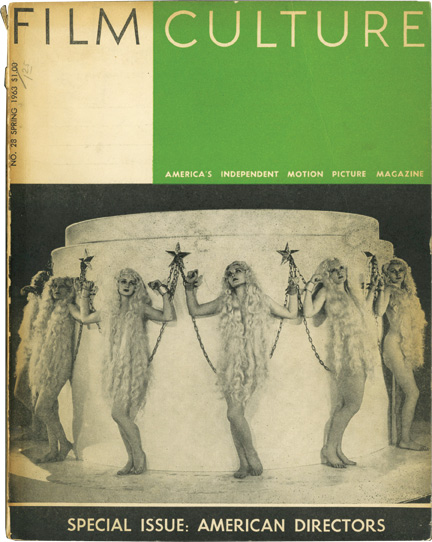

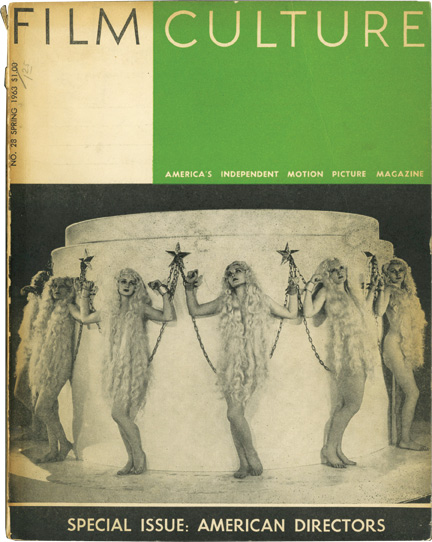

Ever since it came out, I have been stubbornly holding on to the Spring 1963 issue of FILM CULTURE, which features a 68-page extravaganza by Andrew Sarris entitled THE AMERICAN CINEMA. ‘Extravaganza’, is not, I think, an overblown word to use here: the program includes detailed descriptions, evaluations and filmographies of over 100 film directors, with a supplementary list of more than 150 “Other Directors” and a “Directorial Chronology” of American films from l9l5 to 1962. At the time, the very fact that one man had seen enough movies to reach this kind of astronomical overview was staggering enough. Just as challenging — and in its own way, unnerving — were the nine categories under which the first hundred-odd directors were pigeon-holed: “Pantheon Directors,” “Second Line,” “Third Line,” “Esoterica,” “Beyond the Fringe,” “Fallen ldols,” ”Likable But Elusive,” “Minor Disappointments” and “Oddities and One Shots” — an almost metaphysical ordering of the American movie universe that looked so painstaking it was painful — and rather threatening, I believe, even to some of the most veteran of moviegoers. Read more

From American Film (February 1979). This article was specifically conceived as a sort of sequel/companion-piece to “Aspects of the Avant-Garde: Three Innovators,” an article published in American Film almost half a year earlier. This plan was undermined in various ways by the editors, who gave it a title derived from a middle-class French comedy of the period (“Jean-Luc, Chantal, Danièle, Jean-Marie, and the Others”) that caused Akerman herself to reproach me for the piece (assuming that I’d dreamed up that title myself). I no longer recall what my original title was, but I’ve tweaked this piece in a few other minor ways to make it a little less unbearable to me. (By and large, most of my articles written for American Film qualified at least partially as hackwork done to pay my rent.) — J.R.

If American avant-garde films are often chancy to come by, even the most exciting European examples are apt to be regarded in this country as only distant legends. To cite one characteristic but scarcely isolated phenomenon: The welcome once given by the New York Film Festival to the works of Jean-Luc Godard and the team of Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet hasn’t been extended to any of their recent films, and none of the movies of Chantal Akerman has have ever been shown here. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, April 1975 (Vol. 42, No. 496). — J.R.

Petite Marchande d’Allumettes, La

(The Little Match Girl)

France, 1928

Directors: Jean Renoir, Jean Tedesco

Cert-U. dist–Contemporary. p–Jean Renoir, Jean Tedesco . asst. d–

Claude H eymann. Simone Hamiguet. Sc–Jean Renoir. Based on the

storv bv Hans Christian Andersen. ph–Jean Bachelet. a.d—Eric Aës.

m -excerpts from works by –Schubert, Strauss, Wagner, Mendelssohn.

m. d–Manuel Rosenthal, Michael Grant. Lp—Catherine Hessling (Karen,

the Little Match Girl), Jean Storm (Young Man/Soldier), Manuel Raby

[Rabinovitch] (Policeman/Death), Amy Wells (Dancing Doll). 1,030 ft.

29 mins. (16mm; also available in 35 mm.). English titles.

Karen leaves her humble-cottage to sell match boxes under a heavy

Snowfall. She gazes wistfully at a handsome young man emerging

from a restaurant, then looks through a frosted pane at the people

eating inside until boys throw snowballs at her. As she gathers up her

spilled boxes a policeman arrives, and together hey look at a display

of dolls and other toys in a shop window. After lighting matches in

an effort to warm herself, she falls asleep and dreams that she enters

the toy shop — having become the same size as the dolls –- and sets

them all in motion. Read more

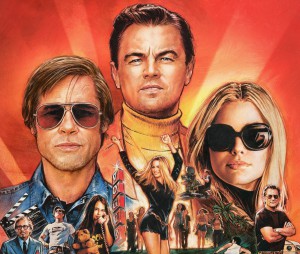

The Spanish monthly film magazine that I write for, Caiman Cuadernos de Cine, invited me in the summer of 2019 to expand on my latest column for them as well as a few Facebook posts about Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. Here is the result. — J.R.

Has 9/11 or the war on terror had any impact on you personally or creatively?

9/11 didn’t affect me, because there’s, like, a Hong Kong movie that came out called Purple Storm and it’s fantastic, a great action movie. And they work in a whole big thing in the plot that they blow up a giant skyscraper. It was done before 9/11, but the shot almost is a semi-duplicate shot of 9/11. I actually enjoyed inviting people over to watch the movie and not telling them about it. I shocked the shit out of them. But, again, I was almost thrilled by that naughty aspect of it. It made it all the more exciting.

But on some level you must have been caught up in the reality of 9/11.

I was scared, like everybody else. “OK, what is this new world we’re going to be living in? Is it going to be fucking Belfast here?” And I didn’t want to fucking fly nowhere. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 29, 1999). — J.R.

Gloria

Rating * Has redeeming facet

Directed by Sidney Lumet

Written by Steven Antin

With Sharon Stone, Jean-Luke Figueroa, Jeremy Northam, Cathy Moriarty, Mike Starr, Bonnie Bedelia, and George C. Scott.

I don’t much relish remakes, especially of movies I like — I’ve avoided seeing the new Payback, a retooling of John Boorman’s Point Blank (1967) — but the idea of Sidney Lumet remaking John Cassavetes’s Gloria (1980) with Sharon Stone seemed to offer possibilities. After all, Cassavetes wrote the script for MGM thinking someone else would direct it; he wound up directing it himself for Columbia only because his wife, Gena Rowlands, was the star and the studio asked him to. “Look, I’m not very bright,” he insisted in an interview. “I wrote a very fast-moving, thoughtless piece about gangsters. And I don’t even know any gangsters. Gloria has a wonderful actress and a very nice kid [John Adames] who’s neither sympathetic nor unsympathetic. He’s just a kid. He reminds me of me — constantly in shock, reacting to this unfathomable environment.” Later he added that when he began shooting Gloria, “I was bored because I knew the answer to the picture the minute we began….All Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 5, 1990). — J.R.

Michelangelo Antonioni’s first feature in color (1964) remains a watermark for using colors creatively, expressionistically, and beautifully; to get the precise hues he wanted, Antonioni had entire fields painted. A newly struck and restored print of the film makes clear why audiences were so excited a quarter of a century ago by his innovations, which include not only expressive uses of color for moods and subtle thematic coding but striking uses of editing as well. This film comes at the tail end of his most fertile period, immediately after his remarkable trilogy consisting of L’avventura, La notte, and L’eclisse; Red Desert may not be quite as good as the first and last of these, but the ecological concerns of this film look a lot more prescient today than they did at the time. Monica Vitti plays an extreme neurotic married to industrialist Richard Harris, and Antonioni does eerie, memorable work with the industrial shapes and colors that surround her, which are shown alternately as threatening and beautiful; she walks through a science fiction lunar landscape spotted with structures that are both disorienting and full of possibilities. Like any self-respecting Antonioni heroine, she’s looking for love and meaning — more specifically, for ways of adjusting to new forms of life — and mainly finding sex. Read more

[IN DREAMS BEGIN RESPONSIBILITIES: A JONATHAN ROSENBAUM READER]

This is an early, abbreviated draft of an introduction to a proposed collection of mine that has subsequently found a publisher (Hat & Beard Press [Los Angeles]/Invisible Republic [Chicago]). I posted this early draft to use in a workshop that I was conducting at Kino klub Split (June 17-22) in Croatia, based on certain concepts proposed in this book. –- J.R.

So complex is reality, and so fragmentary and simplified is history, that an

omniscient observer could write an

indefinite, almost infinite, number of

biographies of a man, each emphasizing

different facts; we would have to read

many of them before we realized that

the protagonist was the same.

Jorge Luis Borges, 1943

I get a great laugh from artists who

ridicule the critics as parasites and

artists manqués —- such a horrible joke.

I can't imagine a more perfect art form,

a more perfect career than criticism. I

can't imagine anything more valuable to

do, and I’ve always felt that way.

Manny Farber, 1977

First, a few ground rules. Because most of us live in a culture where our marketers also tend to be our preferred epistemologists, editors, and censors, I want to override their usual restrictions that govern collections of this kind by drawing upon my literary criticism and my music criticism (mostly of jazz) as well as the film criticism that I’m usually known for, meanwhile charting some of the potential and actual interactivity between these arts in order to define some of the attributes of my own particular niche-market, at least as I’m defining and addressing it here. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 16, 2004). — J.R.

It’s much more of an action flick than either Metropolis or Blade Runner, but there’s a provocative and visionary side to this free adaptation of Isaac Asimov’s SF classic that puts it in the same thoughtful canon. The story is set in Chicago in 2035, and the cityscape, designed by Patrick Tatopoulos, is futuristic yet Victorian around the edges. Built into the mystery plot are reflections about robots as extensions of human will that build up to a wide-ranging but unpreachy critique of everything from corporate malfeasance to the Patriot Act. Will Smith plays an old-fashioned homicide cop investigating the ostensible suicide of a scientist; Bridget Moynahan is an expert in robot psychology. Alex Proyas (The Crow, Dark City) directs a script by Jeff Vintar and Akiva Goldman that’s lively enough to justify a few hokey flourishes. R, 100 min. Burnham Plaza, Century 12 and CineArts 6, Chatham 14, Crown Village 18, Davis, Ford City, Gardens 1-6, Golf Glen, Lawndale, Lincoln Village, Norridge, North Riverside, River East 21, 62nd & Western, Village North, Webster Place. Read more

From Oui (June 1974). –- J.R.

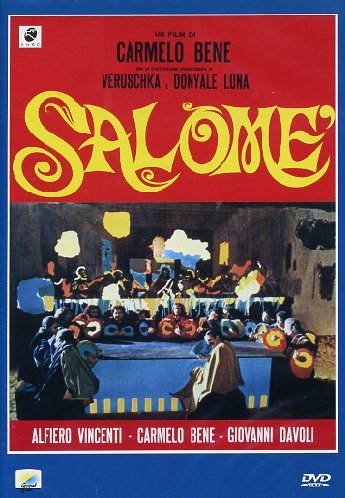

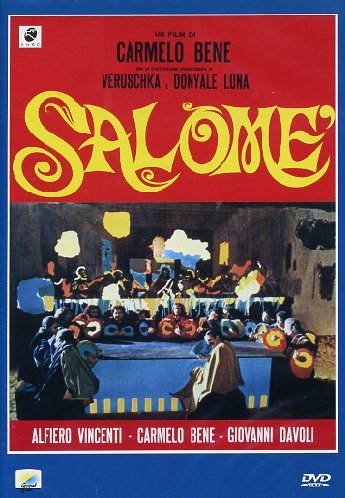

Salome. Meet Carmelo Bene, a vital figure in the Italian avant-garde

whose introduction to American moviegoers is long overdue. Salome,

freely adapted from the Oscar Wilde play, is the latest and perhaps the

most ravishing of his lavish camp spectacles. (Earlier efforts include

Our Lady of the Turcs, Don Giovanni, and One Hamlet Less.)

The title role is played by Veruschka –- the high-fashion model who

writhed under the photographer hero at the beginning of Blow-Up

–- appearing bald, nude, and zombielike as she steps out of the water,

decorated from head to foot with multicolored gems. Bene as Herod

upstages everyone with his hysterical nonstop monologues and

Woody Woodpecker laughs. Visually, it’s a riot of extravagant colors

(fluorescent costumes, Day-Glo sets) and opulent debaucheries

flashing by so quickly that everything remains in delirious flux, and

none of the fancy scenic splendors stands still long enough to be

contemplated. Try to imagine Orson Welles’ Macbeth colored in

with a Fellini paintbox, recut by Kenneth Anger, accompanied by

Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony and the Beer-Barrel Polka,

and you’ll get a fraction of a notion of Bene’s giddy madness.

Depravity, thy name is Salome. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (November 1, 1999). — J.R.

Louis Malle’s seven-part, 378-minute 1968 documentary series is one of my favorites among his works. His upper-class misanthropy and morbidity usually alienate me, but this essayistic travel diary avoids any pretense of objectivity in order to present itself as a highly personal search — narrated in excellent English by Malle himself in the version I’ve seen, but in French with subtitles in this version. In the first episode he addresses the problem of everyone he meets in India describing the country in Western terms, then goes on to reflect on how his filmmaking affects his subjects; from there he takes in everything from a water buffalo being devoured by vultures to interviews with a few European hippies about why they’re in India. With his wide-ranging but rambling approach Malle undoubtedly misses or skimps on certain topics, but his mercurial intelligence keeps this lively and fascinating. (JR) Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 23, 2004). Although I don’t want to begrudge Errol Morris his Oscar, I do wish he’d had more to say in this film about political choices with some bearing on the present. — J.R.

The Fog of War ** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Errol Morris.

In The Fog of War, Errol Morris interviews an 84-year-old Robert S. McNamara, who served as secretary of defense under presidents Kennedy and Johnson and is widely regarded as the architect of the American war in Vietnam. There’s something undeniably masterful about the film, which also includes archival footage, but that mastery is what sticks in my craw: it’s a capacity to say as little as possible while giving the impression of saying a great deal, a skill shared by McNamara and Morris. I’m not sure what we have to gain from this — the satisfaction that we’re somehow taking care of business when we’re actually fast asleep?

This sleight of hand takes many forms, including the film’s title, repeated shots of dominoes lined up on a map of southeast Asia, and the “eleven lessons from the life of Robert McNamara” dispensed in intertitles to introduce the various segments — portentous platitudes ranging from “Rationality will not save us” and “Maximize efficiency” to “Get the data” and “Be prepared to reexamine your reasoning.” Read more

Posted on Film Comment‘s blog, November 16, 2012. — J.R.

Much as Godard’s special brand of cultural tourism quickly became a dominant influence at international film festivals half a century ago, the literal tourism of the late Chris Marker became a major reference point in many of the edgiest offerings at the Viennale, celebrating its 50th anniversary this year. Fittingly, the last to date of the festival’s annual commissioned one-minute trailers, 19 of which were just issued on a DVD, was by Marker himself — a somewhat jaundiced view of the “perfect” film viewer as sought by Méliès, Griffith, Welles, and Godard, eventually and rather sadly achieved in the sad figure of Osama bin Laden watching a Tom and Jerry cartoon on a TV set.

Marker’s more benign influence was especially evident in Jem Cohen’s magisterial Museum Hours, a luminous mix of fiction and essay set in Vienna itself, where it takes the form of a casual friendship developing between a guard at the Kunsthistorisches Art Museum (played by Bobby Sommer — a familiar and friendly Viennale presence, who has worked for many years at its guest office) and a Canadian tourist (Mary Margaret O’Hara) who arrives to visit a dying cousin and turns up at the museum. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 29, 2000). — J.R.

Whether Kenneth Branagh deserves to be regarded as the successor of Laurence Olivier — or even Franco Zeffirelli — when it comes to Shakespeare is far from settled, but this misguided version of one of the Bard’s best comedies strongly suggests he’s the successor of Ed Wood when it comes to musicals. Set in 1939, on the eve of World War II, his feeble attempt to do a 30s musical is so poorly conceived, staged, and edited that it nearly rivals Mae West’s last opus, Sextette. (Peter Bogdanovich’s reviled At Long Last Love is a masterpiece by comparison.) The only performer who emerges unscathed from the clunkiness is dancer Adrian Lester, and so many of Shakespeare’s lines are hacked away to make room for songs by Porter and Berlin that the play is enfeebled in the bargain. Others in the cast include Alessandro Nivola, Matthew Lillard, Natascha McElhone, Alicia Silverstone, Nathan Lane, Carmen Ejogo, Emily Mortimer, and Stefania Rocca. 93 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 30, 2004). — J.R.

Outfoxed: Rupert Murdoch’s War on Journalism

Directed by Robert Greenwald.

DVDs are bringing about rapid and substantial changes in the way we consume movies, and in film culture itself. A case in point is Robert Greenwald’s Outfoxed: Rupert Murdoch’s War on Journalism, which premiered July 13 on DVD and video rather than in theaters. You could have seen it at one of more than 3,000 “house party” viewings organized by MoveOn.org two Sundays ago, or you can just buy it online for $9.95 plus shipping as I did. There must be lots of others like me, because Outfoxed has been Amazon’s top-selling video title for over a week now, and the last time I looked it had 133 customer reviews.

Watching the muckraking examination of the Fox News Channel at home had its advantages: as soon as it was over, I was able to switch directly to Fox to see if it really was as awful as Greenwald’s documentary maintained. (It was.) There are also advantages to keeping a DVD like this on the shelf: you can refer back to certain points in the film for clarification. And facts aren’t all you might want to go back to: if it’s an art film, for instance, you can jump to a favorite passage — a camera movement, a facial expression, a composition, or the delivery of a line of dialogue — the same way you can open a book to revisit some favorite lines of poetry. Read more