Written for Criterion‘s DVD and Blu-Ray of The Immortal Story, released in 2016. — J.R.

Where the story-teller is loyal, eternally and unswervingly loyal to the story, there, in the end, silence will speak. Where the story has been betrayed, silence is but emptiness. But we, the faithful, when we have spoken our last word, will hear the voice of silence…

— Grandmother in Isak Dinesen’s “The Blank Page” (Last Tales)

Virginie had a taste for patterns; one of the things for which she despised the English was that to her mind they had no pattern in their lives. She frowned a little, but let Elishama go on. “Only,” he went on, “sometimes the lines of a pattern will run the other way of what you expect. As in a looking-glass.”

“As in a looking-glass,” she repeated slowly.

“Yes,” he said. “But for all that it is still a pattern.”

— Dinesen’s “The Immortal Story” (Anecdotes of Destiny)

Aside from William Shakespeare, no writer excited Orson Welles’ imagination more than Isak Dinesen (1885-1962) — a Danish baroness who wrote mainly in English — especially when it came to the films he wanted to make. Even though she was born thirty years ahead of him, they shared a capacity to stand outside and beyond their own eras. Both were cosmopolitan 20th century aristocrats with nostalgic yearnings for the 19th century who loved to critique the same romanticism that enveloped them — and florid, masterful storytellers with a developed taste for paradox, irony, and a kind of artifice that unabashedly calls attention to itself. Perhaps no less relevant, both were also tireless polishers of their own art whose apparent simplicity and directness, especially when it comes to the architectonics of “The Immortal Story,” conceal a great deal of subtle craft and nuance.

Welles once even made a pilgrimage to Copenhagen to meet Dinesen, but after a sleepless night he backed away from the prospect and flew back home: “I’d been in love with Isak Dinesen since I’d opened her first book. Tania was somebody I didn’t know. What could a casual visitor presume to offer except his stammered thanks? The visitor would be a bore, and the lover was too humble and too proud for that. I had only to keep silent and our affair would last — on the most intimate terms — for as long as I had eyes to read print.” (“Tania” was Dinesen’s nickname to intimates, and one wonders whether Welles might have named Marlene Dietrich’s aging, world-weary prostitute after her in Touch of Evil.)

Although “The Immortal Story” –– included in Dinesen’s final story collection, Anecdotes of Destiny (1958), and her personal favorite in that volume — was the only one of her tales that yielded a completed film from Welles, at least half a dozen others attracted his attention as a screen adaptor at one time or another. As early as 1953, he planned to include an adaptation of “The Old Chevalier” from her first book, Seven Gothic Tales (1934), in a sketch film for Alexander Korda called Paris By Night, whose other episodes would all be written by himself; and as late as 1985, on the very night that he died, he was planning to shoot part of an another sketch film, Orson Welles Solo, that would have also included his recounting of the same story. His original plan for The Immortal Story was to make it part of an anthology of Dinesen stories — either a TV series or a sketch feature — along with “The Heroine” (from Winter’s Tales, 1942), which he started to shoot with Oja Kodar in Budapest while he was still editing The Immortal Story (and then had to abandon a day later when the promised budget evaporated), “The Deluge from Norderney” (from Seven Gothic Tales), and “A Country Tale” (from Last Tales, 1957). And finally, the most treasured and personal of all his late projects, also starring Kodar, was The Dreamers, worked on between 1978 and 1985, and based on both the story of that title (in Seven Gothic Tales) and its belated sequel, “Echoes” (in Last Tales). (Several excerpts from the half-hour or so of Welles’ sumptuous test footage are visible in a documentary on Criterion’s edition of F for Fake.)

***

Even for a director expected to do the unexpected, The Immortal Story was for many a disconcerting departure for Welles when it premiered theatrically in 1968, in terms of both its seemingly unadorned simplicity and the fact that it was his first released film in color, financed by French television. Although Welles shifted the story’s locale from Canton to Macao and compressed or relocated a few of its narrative details, it generally adheres to the original with rigorous fidelity, including its eerie and singsong repetitions of the same embedded story about a sailor and certain spoken phrases, as well as its meditative, almost ceremonial pacing, which suggests at times a hypnotic trance. (There are only a few rapid cuts — such as when a fancy meal is served, and again when several candles are blown out — reminding one that this is the same Welles who had made Chimes at Midnight just before, and would go on to start The Other Side of the Wind and to make F for Fake afterwards.)

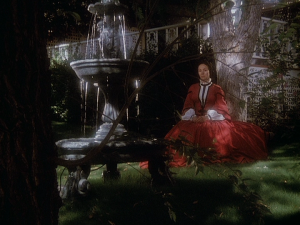

A wealthy, cold-hearted, 70-year-old merchant named Mr. Clay (Welles) contrives to recreate a legendary and fanciful story he once heard from a sailor, enlisting his accountant, Elishama Levinsky (Roger Coggio), to set the machinery in motion by hiring a local courtesan to play a part. She proves to be the daughter, Virginie (Jeanne Moreau), of a merchant Clay drove to suicide years earlier and whose former house he now occupies; the sailor for the story — a Danish teenager named Paul (Norman Eshley) — is chosen at random and summoned on the street by Levinsky and Clay. The various ways in which Clay’s scheme both succeeds and fails over the course of that night constitute the remainder of the tale.

Both the story itself and the tale-within-the-tale are recounted with the sort of elemental purity we associate with myths and fairy tales, and because all four of the characters are solipsistic loners in different ways and mirrors figure often in the settings, repetitions, echoes, and other rhyme effects involving both words and images recur throughout. It is quintessentially a tale about the lures and perils of storytelling itself — that is, the lures and perils of its processes — and about the power plays among its various participants (tellers, listeners, facilitators, and characters), which helps to account for its personal resonance for both Welles and Dinesen. The fact that Dinesen literally dictated this story, like many of her others, to her longtime secretary (and Danish translator, and eventual literary executor) Clara Svendsen must have enhanced her own sense of the interactivity in the yarn-spinning, reflected in Welles’ off-screen narration in the opening stretches of the film’s English version — and even in his willingness, as in the opening of his The Magnificent Ambersons, to let gossiping neighbors take up part of the narrating slack, just as Levinsky later completes the telling of the familiar tale that is started by Mr. Clay.

Given the film’s apparent sparseness, it’s surprising to learn from Jean-Pierre Berthomé and François Thomas’ Orson Welles at Work that it was shot in both France and Spain, using at least three separate Spanish medieval villages to stand in for Macao. For his cinematographer, after four unsatisfactory days with the old-school studio technician Walter Wottitz, Welles turned to a relative novice, Willy Kurant, who had just recently shot features by Agnès Varda and Jean-Luc Godard, using lighter equipment and hand-held camerawork and thus bringing a certain New Wave twist to the film’s overall classicism. (He would later shoot The Deep for Welles.) And even though the shooting lasted only around six weeks, the editing — done at Jean-Pierre Melville’s Paris studio — stretched over the better part of a year. This yielded both an English-language version for eventual theatrical release and a shorter French-language version (with Philippe Noiret dubbing Mr. Clay) for French television, and as Berthomé and Thomas point out, “Although only about twelve minutes in the two versions use different takes, they vary in many other ways, like two competing cuts between which it is impossible to choose.” Clearly making the film for TV played a role in Welles adopting a more minimalist visual and aural palette than was customary for him, as also happened with his 1958 pilot for American TV The Fountain of Youth. In keeping with this simplicity, and with Dinesen’s notion of a blank page as a silence that speaks, a form of Zen-like wisdom, it seems entirely appropriate that The Immortal Story should end with both the unheard song of a seashell and a complete whitening out of the image.

Coincidentally, it was thanks to French television — specifically, a program about Erik Satie that Welles saw roughly halfway through his editing — that Welles decided to use several of the composer’s sadly reflective solo piano pieces for the film’s score, an inspired choice that, as The New Yorker’s Alex Ross has pointed out, “soon became clichéd” because of its frequent use by other filmmakers, but “was quite new in 1968.”

***

According to Dinesen biographer Judith Thurman, this story had a particular personal meaning for its author, having been written after the traumatic dissolution of her intense (albeit chaste) relationship to the Danish poet Thorkild Bjørnvig, for whom she’d served for seven years as muse, literary coach/adviser, and soul mate. Thurman notes that “It was one of the three Dinesen tales concerned with the cosmic meddler, one who, innocent or deluded about his omnipotence, tries to usurp the role of the gods in another person’s life, to introduce his own plans for its development and outcome, to graft his own desire onto its fate-in-progress.” The first of these tales — which for Thurman “anticipated with an uncanny coincidence of detail” Dinesen’s friendship with Bjørnvig — was “The Poet,” written in the early 1930s and the last of the Seven Gothic Tales, immediately following “The Dreamers.” And the third was “Echoes,” her sequel to “The Dreamers,” which for Thurman “was the epitaph of that friendship.” Hence “The Immortal Story,” the centerpiece of this trio, can be read as her complex reflections about her own “cosmic meddling” in the life and destiny of Bjørnvig.

Given Welles’ appropriation of both “The Immortal Story” and “Echoes” (not to mention the latter’s prequel, “The Dreamers”) into his own oeuvre, it is difficult not to find personal investments of his own in this highly allegorical material. “The Dreamers” recounts the story of a famous opera singer named Pellegrina who, after losing her singing voice, resolves to disappear from her life and lead many other, different lives; “Echoes” charts one of those lives, when she tries to mentor a boy in a remote country village with a beautiful voice who reminds her of her former self, and he winds up denouncing her as a witch.

The fact that Welles shot many of the interiors of The Immortal Story in his own villa near Madrid, including much of Clay’s house, and all of the material for The Dreamers in his own house and backyard in Hollywood, seems to support his personal relation to these stories, even though practical concerns also must have played a part in these decisions. Welles’ own long-term relationship with Oja Kodar — who served as his muse, but whom he also mentored — undoubtedly also played a part, even when it came to The Immortal Story. When I first met her in 1986, a few months after Welles’ death, she told me that the first work she ever did on one of his films was dubbing Virginie’s “lovemaking sighs” during her night with Paul. (In fact, it seems she was alluding to the character’s gasp at the moment of orgasm, when she relives the loss of her virginity with an English captain by experiencing an earthquake — an abrupt punctuation to a soundtrack otherwise dominated here by the delicate and intricate orchestration of the chirping of crickets. And clearly part of what “The Dreamers” meant for him related to his identification with Pellegrina (and, by extension, with Kodar) as well as her own best friend and facilitator, a wealthy Dutchman named Marcus Cocoza (whom he played himself), like the character Levinsky, a Jew; and in “Echoes,” one suspects he identified in different ways with both Pellegrina and her young pupil.

So it isn’t really a stretch to say that in The Immortal Story, Welles identifies with all the major characters — Clay, Elishama, Paul, and Virginie (the last two of whom comprise a clear literary allusion to Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre’s celebrated 1788 novel Paul et Virginie, one of the key romances read by Flaubert’s Emma Bovary roughly half a century later). Indeed, the fact that both he and Dinesen identify with all four, in equal measures, is central to the story’s primal power.

This cross-identification points to something else these two larger-than-life artists shared, a certain fluidity regarding gender when it came to projecting themselves in others. Dinesen was often called a diva, and Welles was sometimes regarded as a dandy, but clearly it doesn’t do justice to either of their respective temperaments and self-images to limit them to such stereotypes. It would be far more accurate to say that both of them were divas and dandies, at the same time and at every moment.