From the Chicago Reader (October 1, 2000). MUBI has offered this film in the past. — J.R.

Scripted and directed by Ko I-Chen — a member of the Taiwanese new wave best known as an actor outside of Taiwan, particularly for his role in Edward Yang’s Taipei Story — this exciting 1997 feature, Lan yue, consists of five 20-minute reels designed to be shown in any order, so that 120 versions of the film are possible. (Ko wrote all five scripts simultaneously, on different colored sheets of paper.) In most respects this is a conventional, even commercial narrative feature, which makes for what I like most about it — it demands the viewer’s creative participation at the same time that it pretends to satisfy all the usual expectations. All five reels feature more or less the same characters and settings — including a young woman, a writer, a film producer, and a restaurant owner, all of whom live in Taipei and belong to the same circle — but in each reel the woman is involved with one of two men. One can construct a continuous narrative by positing some reels as flashbacks, as flash-forwards, or as events that transpire in a parallel universe. Read more

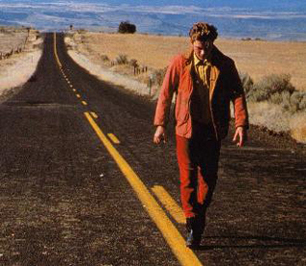

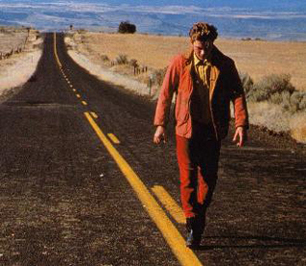

Gus Van Sant’s 1990 feature, his best prior to Elephant, is a simultaneously heartbreaking and exhilarating road movie about two male hustlers (River Phoenix and Keanu Reeves) in the Pacific northwest. Phoenix, a narcoleptic from a broken home, is essentially looking for a family, while Reeves, whose father is mayor of Portland, is mainly fleeing his. The style is so eclectic that it may take some getting used to, but Van Sant, working from his own story for the first time, brings such lyrical focus to his characters and his poetry that almost everything works. Even the parts that show some strain — like the film’s extended hommage to Orson Welles’s Chimes at Midnight — are exciting for their sheer audacity. Phoenix was never better, and Reeves does his best with a part that’s largely Shakespeare’s Hal as filtered through Welles. 102 min. (JR)

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 1, 1997). — J.R.

This 1996 film by Mohsen Makhmalbaf is one of his most seminal and accessiblea reconstruction of a pivotal incident during his teens that landed him in prison for several years during the shah’s regime. A fundamentalist and activist at the time, Makhmalbaf stabbed a policeman; as a consequence he was shot and arrested. Two decades later, while auditioning people to appear in his film Salaam Cinema, he encountered the same policeman, now unemployed, and the two wound up collaborating on this film about the incident involving them, trying (with separate cameras) to reconcile their versions of what happened. Though no doubt prompted in part by Abbas Kiarostami’s Close-Up (1990), this is a fascinating humanist experiment and investigation in its own right, full of warmth and humor as well as mystery. The original Persian title, incidentally, translates as Bread and Flower. In Farsi with subtitles. 78 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, December 1974 (Vol. 41, No. 491). — J.R.

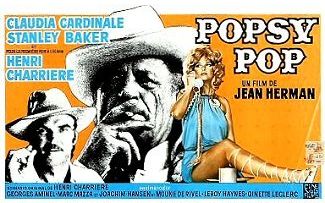

Popsy Pop (The 21 Carat Snatch)

France/Italy, 1970

Director: Jean Herman

Guiana. Plateau, Venezuela. In a ramshackle ‘boom town’, occupied by the natives who work the local diamond mine, the glamorous Popsy Pop arrives –ostensibly to divert the workers with her sexy cabaret act, but actually in order to distract Silva, the mine-company inspector, from a two-million-dollar diamond heist planned for the night of her arrival. Masterminded by Marcou, an ageing criminal who loves Popsy Pop, and carried out with the help of his henchmen Tormenta, Blanchette and Freddy -– who pilots the getaway helicopter — the robbery proceeds as planned: Silva is knocked unconscious in the singer’s dressing room and the diamonds are taken from the company office. But Popsv Pop and Freddy betray the rest of the gang by leaving without them. The angry workers kill Blanchette and Tormenta, but Silva persuades them to spare Marcou in the interests of recovering the diamonds — and offers the latter a cut of the reward in addition to a chance to avenge Popsy Pop’s double-cross. She has meanwhile taken a plane to Santa Domingo with Freddy, and places the diamonds in a safe deposit box, hiding the key in a jar of cold cream. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 11, 1998). — J.R.

The Eel

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Shohei Imamura

Written by Motofumi Tomikawa, Daisuke Tengan, and Imamura

With Koji Yakusho, Misa Shimizu, Fujio Tsuneta, Mitsuko Baisho, Akira Emoto, and Sho Aikawa.

I’ve seen only five of Shohei Imamura’s 19 features, most of them so many years apart that it’s hard to see many stylistic or thematic connections. Yet there’s no doubt in my mind that his 18th, The Eel (1997) — which shared last year’s Palme d’Or with Taste of Cherry and opens this week at the Music Box — is the most interesting new movie around: funny, lyrical, provocative, imaginative, and consistently entertaining. That it happens to be Japanese is incidental to its interest, though I suppose a lot of people won’t go to see it because it isn’t in English. (I suspect the problem isn’t so much xenophobia as habit; most Americans have never seen a subtitled movie and probably regard the prospect of seeing one as work.)

It’s been a truism for quite some time that the Japanese cinema is in terrible shape, financially and aesthetically (particularly now that Akira Kurosawa has died) — though it’s not clear to what extent one should believe the overseas commentators who sift through the available evidence. Read more

This comes from my Spring 2010 DVD column in Cinema Scope. — J.R.

Hipsters/Stilyagi. I include the Russian as well as the English title of this big-budget, post-modernist 2008 Russian musical about teenagers, directed by Valery Todorovsky, because as far as I know, the Russian DVD, sans subtitles, is the only version available, at least on Amazon. This movie was the opening night attraction at the Tromsø International Film Festival in the northernmost reaches of Norway, which was celebrating its 20th anniversary in January, and I must confess that I didn’t expect to enjoy it nearly as much as I did, especially because it could be described with fair accuracy as the Russian equivalent of Rob Marshall at his cheesiest, set in 1950s Moscow, and is full of preposterous plot developments. But then again, shame on me, I also enjoyed watching Daniel Day-Lewis in Nine, even after loathing every minute of Chicago, so maybe you shouldn’t trust me. All I can say is that I sufficiently enjoyed Hipsters, partly for its curiosity value and partly for its sheer pizzazz — without ever imagining that it had anything to do with Russian history or the history of the musical, Russian or otherwise — to order the unsubtitled version of it from Amazon. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (December 1, 1990). Twilight Time has recently released this on Blu-Ray. — J.R.

Glasnost or no glasnost, the cold war still rages here for CIA officials, who manage to ensnare a British publisher and jazz musician (Sean Connery) in a plot to intercept a book by a distinguished Soviet scientist (Klaus Maria Brandauer); the scientist has spilled the beans about the Soviet defense program, and his book editor (Michelle Pfeiffer) becomes an unwitting pawn in the spy network. Part of what makes this a top-notch thriller (as well as a touching love story) is the literacy and intelligence of the dialogue, adapted by playwright Tom Stoppard from John Le Carre’s novel; another part is the taut professionalism of director Fred Schepisi, who knows precisely when to cut away to eavesdropping spies or fleeting flashbacks in order to add flavor or tension. But the film has many other virtues as well: the most thoroughgoing and effective use of Moscow and Leningrad locations ever in an American film, a good score by Jerry Goldsmith (with Branford Marsalis dubbing Connery’s soprano sax solos), first-rate performances from the leads (Pfeiffer is especially fine), and a well-trained secondary cast including Roy Scheider, James Fox, John Mahoney, Michael Kitchen, J.T. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (December 1, 1990). — J.R.

A beautiful and disturbing 1965 feature by Agnes Varda about family happiness, full of lingering and creepy ambiguities. A happily married carpenter (Jean-Claude Drouot) with a beautiful wife (Claire Drouot) and two small children (Sandrine and Oliver Drouot) falls in love with a beautiful postal clerk (Marie-France Boyer), who becomes his mistress. After the wife dies for mysterious reasons (whether by accident or suicide isn’t clear), his idyllic family life continues with the postal clerk. Provocative and lovely to look at, this is one of Varda’s best and most interesting features (along with Cleo From 5 to 7 and Vagabond). (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (December 21, 1990). — J.R.

Francis Coppola’s tragic and worthy (if uneven) conclusion to his Godfather trilogy, which he wrote in collaboration with Mario Puzo, represents a certain moral improvement over its predecessors by refusing to celebrate and condemn violence and duplicity in the same breath, or at least to the same degree. For 161 minutes, Michael Corleone (Al Pacino at his best) seeks absolution for his past sins, and although a cardinal grants it at one point (in a powerful confession scene), the film itself refuses to. While some of the allegorical implications persist (crime equals capitalism, Mafia equals family, both equal America), the decline of America in a world market where both European money and the Vatican are made to seem as corrupt as the Corleones leads to an overall change of focus; it ultimately lands this film in a metaphysical realm where the very plot seems formalized into semiabstract rituals. The inflated sense of self-importance in part two — epitomized by the playing of Nino Rota’s ubiquitous waltz theme on a church organ during a communion — is somewhat muted here, although a virtuoso set-piece climax finally strains credulity when too many important events dovetail in a single sequence. Read more

This interview, conducted by phone, appeared in my favorite French weekly magazine, Les Inrockuptibles, in a special double issue devoted largely to American cinema (6-19 août 1997, no. 114); I have this text only in French. — J.R.

Enfant de la balle du Sud profond, passionnant théoricien autodidacte, critique original qui préfère Jerry Lewis à Woody Allen, Jonathan Rosenbaum fait le lien cinéphile entre les Etats-Unis et le reste du monde : comment le cinéma mondial touche ou ne touche pas le public américain, comment le cinéma américain est ou n’est pas une émanation du système capitaliste.

De l’Alabama profond aux Straub : on pourrait résumer ainsi le parcours cinéphilique extraordinaire de Jonathan Rosenbaum. Né en 43 et élevé à Florence, petite ville de l’Alabama, Rosenbaum est ce qu’on peut appeler un ciné-fils, dans l’acception la plus prosaïque du mot de Serge Daney : son père et son grand-père géraient un petit circuit de salles à Florence et alentour. Rosenbaum est donc tombé dedans quand il était petit, voyant des films quotidiennement depuis l’âge de 6 ans, essentiellement le tout-venant de la production commerciale hollywoodienne. Une période qu’il a brillamment chroniquée dans sa biographie Moving places. Read more

From the Chicago Reader, November 1, 1992.

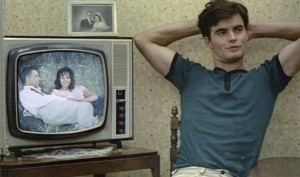

This brilliant hour-long video transferred to film (1992) by independent filmmaker Mark Rappaport (The Scenic Route) is in effect a subversive piece of film criticism that departs from the fictional conceit of Hudson himself (represented through clips from his films and by actor Eric Farr) speaking from beyond the grave about his homosexuality and what this did or didn’t have to do with his countless heterosexual screen roles. Part of what emerges, to hilarious effect, is the extraordinary amount of male cruising and number of barbed allusions to Hudson’s gayness that his movies of the 50s and 60s contain; what also emerges is the sexual ideology of the period. Though much of this essential work is extremely funny, it is also very much about death in relation to movies. 63 min.

Read more

From the February 12, 1998 Chicago Reader.

Robert Duvall is the writer, director, executive producer, and star of this commanding 1997 portrait of a southern Pentecostal preacher, but far from being any sort of one-man show, this feature is powerful mainly for what it has to say about a community and a way of life. Duvall’s character is a troubled and troubling scoundrel who critically assaults a younger preacher (Todd Allen) who’s taken his wife (Farrah Fawcett), then hightails it from Texas to Louisiana in flight from the law to start a new congregation. He remains a morally ambiguous figure throughout, but in defiance of the usual Elmer Gantry stereotype, the film never questions the sincerity of his religious beliefs. The fact that he’s inspired by black preachers and preaches to integrated (but mainly black) congregations only adds to the complicated response we’re invited to have, though Duvall’s direction of a mix of professional and nonprofessional actors, especially in the extended church sessions, is never less than masterful. His gifts for storytelling are more uneven but, under the circumstances, less relevant. A fresh and open-minded look at a major strain in American life that’s rarely depicted with any lucidity, this is an invigorating achievement. Read more

Commissioned by Caboose Press for a forthcoming volume on Godard and posted here prematurely. — J.R.

François Truffaut

‘Un Trousseau de fausses clés’, Cahiers du Cinéma 39 (October 1954): 45–52.

I have often wondered why my favourite piece of film criticism by François Truffaut — ‘Un trousseau de fausses clés’, the final essay devoted to Alfred Hitchcock that appears in Cahiers du Cinéma No. 39, in October 1954, the first special issue of that magazine devoted to Hitchcock. — has never been included in any of Truffaut’s books. The likeliest reason is that Truffaut begins his article by responding to André Bazin’s essay in the same issue — pointedly called ‘Hitchcock contre Hitchcock’, maintaining that Hitchcock tended to tell his interviewers whatever they wanted to hear — by conceding that Hitchcock was something of a liar. Given Truffaut’s cordial relations with Hitchcock that ultimately led to his book-length interview with him, reprinting an essay that began with and then pondered the implications of such an assertion was something to be avoided.

Even so, the absence of this seminal essay from Truffaut’s ‘official’ critical oeuvre has been unfortunate, especially because it has obscured its importance as a major influence on Truffaut’s critical colleagues—most notably on Éric Rohmer and Claude Chabrol, in their pioneering 1957 book on Hitchcock, which alludes twice to this essay (without, however, providing a specific reference to it) and recapitulates much of its central analysis; on Jean-Luc Godard, in his own most ambitious and exhaustive critical analysis of a film, ‘Le Cinéma et son double’ (Cahiers du Cinéma issue no. Read more

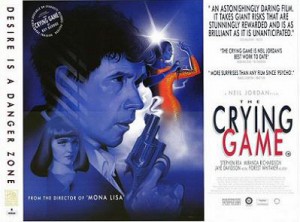

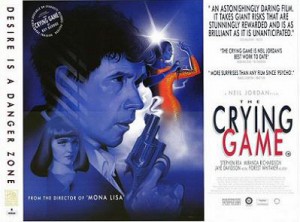

From the Chicago Reader (December 18. 1992). I was reminded of this capsule by Thom Andersen’s references to it when he reviewed The Crying Game at length for the Reader, in an essay reprinted in his excellent recent collection, Slow Writing. — J.R.

An adroit piece of story telling from Irish writer-director Neil Jordan (Mona Lisa, The Miracle) that is ultimately less challenging to conventional notions about race and sexuality than it may at first seem. Like other Jordan features, this one centers on an impossible love relationship, and the covert agenda of the plot is to keep it impossible by any means necessary. The theories of literary critic Leslie Fiedler about the concealed and unconsummated lust of the white male for the nonwhite male in such American classics as Huckleberry Finn and Moby Dick seem oddly relevant to certain aspects of this tale about an IRA volunteer (Stephen Rea) who assists in the kidnapping of a black British soldier (Forest Whitaker) and subsequently becomes involved with his mulatto lover (Jaye Davidson) in London; the plot, held in place by a parable about a scorpion and a frog that’s filched from Orson Welles’s Mr Arkadin, features a startling twist about halfway through; among the cleverly concealed safety nets that hold this movie’s conceits in place is an implied misogyny that only becomes evident once the story is nearly over. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 28, 1997). — J.R.

A pared-down crime thriller set mainly in Reno, this first feature by writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson is impressive for its lean and unblemished storytelling, but even more so for its performances. Especially good is Philip Baker Hall, a familiar character actor best known for his impersonation of Richard Nixon in Secret Honor; he’s never had a chance to shine on-screen as he does here. In his role as a smooth professional gambler who befriends a younger man (John C. Reilly), Hall gives a solidity and moral weight to his performance that evokes Spencer Tracy, even though he plays it with enough nuance to keep the character volatile and unpredictable. Samuel L. Jackson and Gwyneth Paltrow, both of whom have meaty parts, are nearly as impressive, and when Hall and Jackson get a good long scene together the sparks really fly. Pipers Alley. — Jonathan Rosenbaum

Read more

Read more