Posted on the web site Wellesnet. I’ve added a few illustrations of my own to the original, conducted by Lawrence French.

Having worked as a consultant on the completion of The Other Side of the Wind, I’m no longer sure that all my comments about the film found below would still hold. — J.R.

Jonathan Rosenbaum has long been an astute critic on the cinema of Orson Welles, frequently writing about Welles’ films. He served as the consultant for the re-edited version of TOUCH OF EVIL, and edited THIS IS ORSON WELLES, the seminal book of Welles interviews, conducted by Peter Bogdanovich.

The following interview has been combined from two separate conversations. The first took place in the fall of 1998, after the release of the re-edited version of TOUCH OF EVIL, and focused on the problems inherent in changing TOUCH OF EVIL to what Welles requested in a memo written 41 years earlier. The second interview occurred in January, 2003, and covers Welles’ two

LAWRENCE FRENCH: Does the film museum in Munich now have most of the unfinished Welles films? Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 1, 1994). — J.R.

One of the delightful things about Rose Troche’s stylish, low-budget, filmed-in-Chicago black-and-white lesbian comedy is that its characters all register as real people, even when bits of the dialogue are stiff or some of the lip sync is off; this isn’t a movie about lesbians, it’s a movie about these lesbians, and we’re likely to think of them afterward as if they were people we knew. As in the better American underground movies of the 60s, which this sometimes resembles, the youthfulness and the footloose free spirit — evident in everything from the performances and Ann T. Rossetti’s shooting style to Brendan Dolan and Jennifer Sharpe’s jazz score and the breezy rhythmic stretches bridging narrative sequences — keep things bouncing along like a clear spring day. (And though the characters themselves vary in age, there’s a clear note of shared adolescent braggadocio in the way that sex and romance here become real only after they’re talked about and described.) Written as well as produced by Troche in collaboration with Guinevere Turner, the younger of the two romantic leads (the other is V.S. Brodie), this movie dives into fantasy and stylized internal monologues with the same aplomb it brings to the buildup to a hot date. Read more

Written for The Unquiet American: Transgressive Comedies from the U.S., a catalogue/ collection put together to accompany a film series at the Austrian Filmmuseum and the Viennale in Autumn 2009. — J.R.

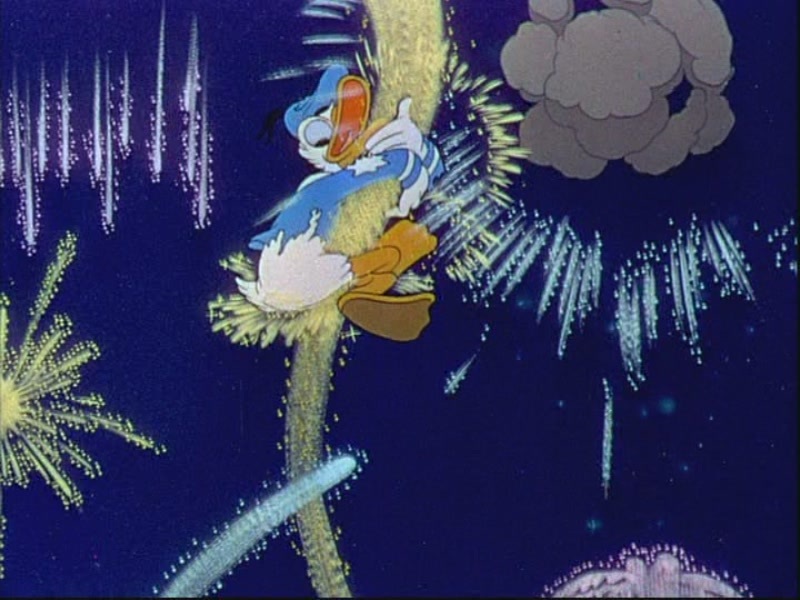

After Orson Welles tried to implement Nelson Rockefeller’s

Good Neighbor policy with South America

in an unfinished episodic film, It’s All True (1942),

scandalizing both RKO and Latin American dignitaries

by focusing on poor and nonwhite characters,

Walt Disney dutifully offered a more conventionally

touristic and clearly segregated view of the

Continent, and succeeded spectacularly with the

same studio and many of the same dignitaries (as well

as with general audiences in both the U.S. and South

America) by offering this kitschy and visually extravagant

episodic, 70-minute film (1945), his first feature

to combine animation with live action. The title

pals are the infantile Donald Duck playing an American

tourist and the somewhat older Brazilian parrot

Joe Carioca and Mexican rooster Panchito, the latter

two playing Donald’s principal tour guides. The film

begins somewhat conventionally with tales about

Pablo, a South Pole penguin longing for warmer surroundings

who sails up the coast of Chile and Peru,

and a Uruguay boy gaucho who enters a flying donkey

in a race. Read more

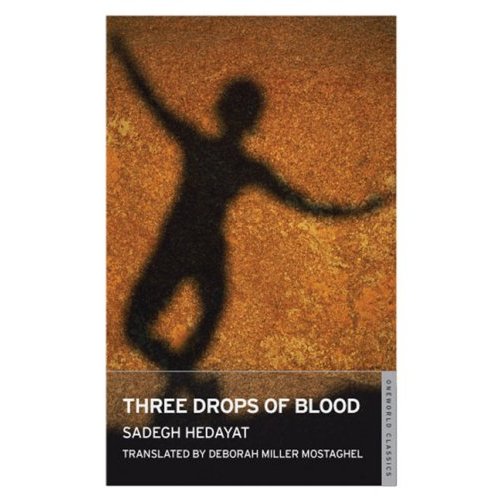

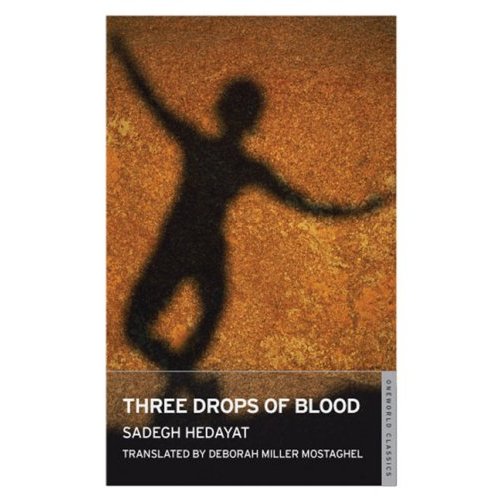

I find it curious that the great Iranian prose writer Sadeq Hedayat (1903-1951) should remind me so much of Edgar Allan Poe, because their backgrounds couldn’t be more dissimilar. Poe (1809-1849) was poor his entire life and Hedayat came from a very wealthy and privileged background; Poe lived in several American cities but never left the U.S. whereas Hedayat lived for extended periods in Belgium, France, and India as well as Iran.

Before the recent publication of Three Drops of Blood, a collection of Hedayat stories, I’d read only his novella The Blind Owl (1936), one of the most terrifying and unsettling horror stories I know, as well as a few of his other stories in French. It seems that most of his work is (or at least has been) available in French, but until the appearance of this slim anthology, The Blind Owl–freely if brilliantly adapted by Raul Ruiz in one of his craziest features, La Chouette Aveugle (1987)–has been virtually the only thing of his available in English. (12/25 postscript: Adrian Martin has just informed me that one can access many Hedayat stories in English translation, including The Blind Owl, for free here. Read more

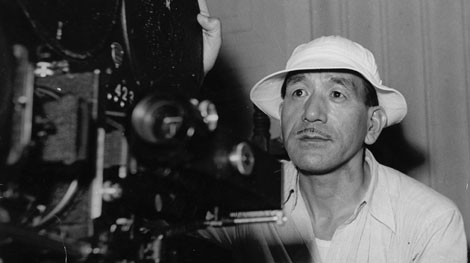

From Sight and Sound (Autumn 1972). I like the recent second edition of this a lot more — enough to have given it a blurb that’s used in the ads, and not only because Schrader cites me in his new introduction about “slow films”. — J.R.

TRANSCENDENTAL STYLE IN FILM: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer

By Paul Schrader

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS, $10.00

Modesty and caution are not exactly what one expects to find in a book with this title, on these three directors; but ironically, one of the chief limitations of this comparative study is that these qualities often seem to predominate over everything else. The first ‘step’ of transcendental style,for instance, is defined as follows: ‘The everyday: a, meticulous representation of the dull, banal commonplaces of everyday living’ or what [Amédée] Ayfre quotes Jean Bazaine as calling “le quotidien”.’ Not quite a double redundancy, but close enough to make one wonder why this passage and so many comparable ones suggest a critic walking on eggshells.

Although it is nowhere identified as such, Schrader’s extended essay has much of the look, shape and sound of a doctoral dissertation [2013 note: I believe that this was in fact a Masters’ thesis]. 194 footnotes are appended to 169 pages of text, and each step of the argument proceeds like a slow-motion exercise in which every inch of terrain must be defined and tested before it can be touched upon. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 1, 1997). — J.R.

This creepy Woody Allen musical (1996) has got to be the best argument ever against becoming a millionaire. It unwittingly reveals so many dark facets of the filmmaker’s cloistered mind that one emerges from it as from a crypt, despite the undeniable poignance of some of the musical numbers (the best of which hark back to Guys and Dolls in displaying the vulnerability of the amateur performers). This isn’t only a matter of how Allen regards the poor, nonwhite, sick, elderly, and incarcerated segments of our society, how he feels about the ethics of privacy, or what he imagines his rich upper-east-side neighbors are like. In this characterless world of Manhattan-Venice-Paris, where love consists only of self-validation and political convictions of any kind are attributable to either hypocrisy or a brain condition, the me-first nihilism of Allen’s frightened worldview is finally given full exposure, and it’s a grisly thing to behold. With Goldie Hawn, Alan Alda, Drew Barrymore, Lukas Haas, Julia Roberts, Tim Roth, and Natalie Portman. R, 101 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

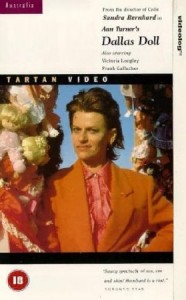

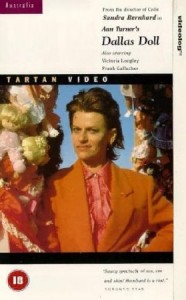

From the November 7, 1997 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

This 1994 feature is much too goofy to qualify as an absolute success, but it’s so unpredictable, irreverent, and provocative that you may not care. Australian writer-director Ann Turner has a lot on her mind, and it’s unlikely you’ll be able to plot out many of her quirky moves in advance. Imagine Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Teorema (with Sandra Bernhard in the Terence Stamp part, seducing most of a bourgeois Australian family and enough other country-club notables to wind up as mayor) crossed with Repo Man and you’ll get some notion of the cascading audacity. This is a satire about foreign invasion in which America (in the form of Bernhard, a spiritual “golf guru”), then Japan, and finally extraterrestrials in a spaceship all turn up to claim the land down under as their own. Along the way Turner gives us delightfully incoherent dream sequences, bouts of strip miniature golf, some hilarious lampooning of the new-age mentality, and one of my favorite performances by a dog. Incidentally, Bernhard despises this movie and trashes it whenever she gets a chance, but I liked it as well as or better than many of her routines. Read more