From Monthly Film Bulletin, December 1976 (Vol. 43, No. 515). — J.R.

One Second in Montreal

Canada, 1969

Director: Michael Snow

Dist–London Filmmakers’ Co-op/Cinegate. p.c /p/ph/ed–Michael Snow. 612 ft. (at 16 f.p.s.) 26 mins.; (at 24 f .p.s.) 17 mins.

A series of thirty-odd black and white still photographs – all showing park sites for a projected monument in Montreal covered with blankets of snow — are rephotographed and shown in succession; the duration of each photograph on the screen progressively increases during the first section of the film, and progressively decreases during the second, which ends with a ‘flash’ repeat of the initial title card. A simple experiment in what might be described as the phenomenology of duration in relation to the viewer’s attention and grasp of detail, One Second in Montreal apparently owes its title to the fact that the combined exposure time of the original photographs adds up to only one second.

Praised somewhat hyperbolically as a “cinematic construction which plays upon the seriality of film images” (Annette Michelson) and a “snow film so silent you can hear the snow fall” (Jonas Mekas), the film is an ‘open’ work in the sense that it can be projected at either 16 or 24 frames per second. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 8 , 1993). — J.R.

Let’s start with the bad news, which also happens to be the good news. With the erosion of state funding virtually everywhere and the concomitant streamlining of many film festivals toward certifiable hits — basically what an audience already knows, or worse, what it thinks it knows — there isn’t a great deal of difference anymore between the lineups of most large international festivals, including Cannes, Berlin, Venice, Toronto, and even Chicago. By and large, the critics at Toronto last month, myself included, who thought it was an unusually good festival were those who hadn’t made it to the previous three big festivals.

Some films don’t make every list, of course. Luc Moullet, probably the most gifted comic filmmaker working in France, almost never seems to attract international interest, and I was disappointed to discover that his delightful Parpaillon, which I saw in Rotterdam, was passed over by Toronto, Chicago, and New York. The same goes for Robert Kramer’s Starting Place, which I saw in Locarno — a beautifully edited and moving personal documentary about contemporary Vietnam. I’m also sorry that Hou Hsiao-hsien’s The Puppetmaster and an intriguing American independent effort called Suture, both of which I saw in Toronto, are missing from the Chicago roster. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (August 1, 1987). — J.R.

Kevin Costner, suffering as nobly here as in The Untouchables, plays a naval officer hired by the secretary of defense (Gene Hackman), whose mistress he has been unwittingly sharing. While credited as an adaptation of Kenneth Fearing’s novel The Big Clock (which was already made into a movie in 1948, directed by John Farrow), this taut thriller adds so many twists of its own it might be more appropriately cross-referenced with The Manchurian Candidate, even though it isn’t nearly as daffy or as mercurial. Cornball Dolby effects aside, it’s the kind of intricately plotted suspense film with juicy secondary parts (Sean Young, Will Patton, George Dzundza, Iman, Howard Duff) that used to be churned out in the 1940s; Roger Donaldson, the New Zealand director of Smash Palace, The Bounty, and Marie, delivers coproducer Robert Garland’s efficient script with more bombast than brilliance, but at least it keeps you in your seat (1987). (JR)

Read more

Read more

An unexpected gift arrives in the mail: a subtitled preview of Peter von Bagh’s fabulous and rather Markeresque documentary (2008)—a lovely city symphony which is also a history of Helsinki (and incidentally, Finland, Finnish cinema, and Finnish pop music) recounted with film clips and paintings by three voices (two male, one of them von Bagh’s, and one female—each one reciting what seems to be a slightly different style of poetic and essayistic discourse). There are no chapter divisions on this DVD, and the continuity is more often geographical than chronological, although there’s also a lot of leaping about spatially as well as temporally. At separate stages we’re introduced to the best-ever Finnish camera movement and the best Finnish musical, are invited to browse diverse neighborhoods and eras (and to ponder contrasts in populations and divorce rates), and are finally forced to admit that a surprising amount of very striking film footage has emerged from this country and city.

Peter von Bagh—prolific film critic, film historian, and professor, onetime director of the Finnish Film Archive and current artistic director of two unique film festivals, the Midnight Sun Film Festival (held in Sodankylä, above the Arctic Circle, during what amounts to one very long day in the summer, when there’s no night) and Il Cinema Ritrovato (held soon afterwards, in Bologna)—is the man who convinced me to purchase my first multiregional VCR in the early 80s. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 16, 1987). Mamet’s first feature and still his best.– J.R.

Hitchcock lives! David Mamet’s first time out as a director is a thriller about compulsive behavior and con games, done with a sureness of touch and taste that shows a better understanding of Hitchcockian obsessions than the complete works of Brian De Palma. The viewer has to adjust to Mamet’s theatrical reflexes, which impart a certain strangeness to both the performances and the staging — such as confidential conversations held within earshot of characters who don’t hear them, because the conventions of theater space are employed rather than the usual conventions of filmic space. But once past this barrier, one is easily seduced by Mamet’s storytelling gifts, which deliver a shapely script (developed with Jonathan Katz), full of its own con games and compulsions, with an adroit grasp of emphasis and pacing. Lindsay Crouse (Mamet’s wife) plays a successful upper-crust psychiatrist and author whose feelings of frustration in treating her criminally involved patients goad her into a walk on the wild side, beginning with the eponymous gambling den, with Joe Mantegna as her guide. Apart from uniformly fine performances — with Mike Nussbaum, Lilia Skala, and J.T. Read more

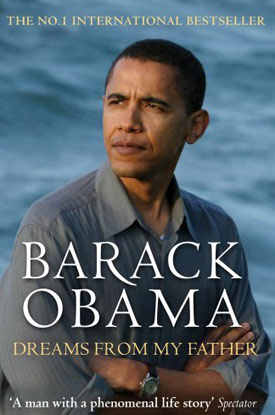

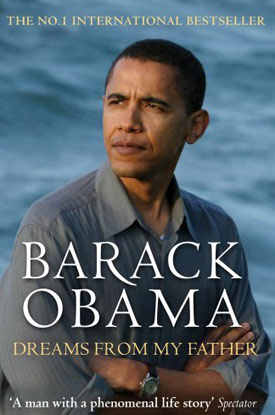

DREAMS FROM MY FATHER: A STORY OF RACE AND INHERITANCE by Barack Obama (New York: Three Rivers Press) 1995, 480 pp.

This book, which I’m still reading (I’m in its final section, about Kenya), is considerably more powerful, both as writing and as autobiography, than Obama’s follow-up book, The Audacity of Hope: Thoughts on Reclaiming the American Dream. For me the most striking episode so far occurs in New York, and, significantly enough, it occurs at the movies. (Most of the gist of this episode can be found on pp. 123-125, towards the end of the first of the book’s three main sections, “Origins”.)

During a visit from Obama’s (white) mother, she finds an ad for a downtown revival of Black Orpheus in the Village Voice, which she describes as the first foreign film she ever saw, when she was 16 and in Chicago and “thought it was the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen.” She and Obama and his sister Maya go to the revival house in a cab (the cab is a typically telling novelistic detail), and halfway through the picture Obama finds himself seething at what he finds racist and paternalistic in this white, French depiction of black and brown Brazilians in the Rio favelas during Carnival — which he describes as “the reverse image of Conrad’s dark savages” [in Heart of Darkness]. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 1, 1988). — J.R.

Treated as a debacle upon release, partially as payback for producer-star Warren Beatty’s high-handed treatment of the press, this Elaine May comedy was the most underappreciated commercial movie of 1987. It isn’t quite as good as May’s previous features, but it’s still a very funny work by one of this country’s greatest comic talents. Beatty and Dustin Hoffman, both cast against type, play inept songwriters who score a club date in North Africa and accidentally get caught up in various international intrigues. Misleadingly pegged as an imitation Road to Morocco, the film is better read as a light comic variation on May’s masterpiece Mikey and Nicky as well as a prescient send-up of blundering American idiocy in the Middle East. Among the highlights: Charles Grodin’s impersonation of a CIA operative, a blind camel, Isabelle Adjani, Jack Weston, Vittorio Storaro’s cinematography, and a delightful series of deliberately awful songs, most of them by Paul Williams. 107 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

Early in 2009, I received a phone call from Béla Tarr, asking me if I could write a page about Sátántangó (1994) for a Hungarian newspaper to celebrate its 15th anniversary. Here’s what I sent him. —J.R.

Sátántangó at 15

Congratulations to Sátántangó on its 15th anniversary. Now that it’s a teenager, I’m happy that English-speaking fans can finally, at long last, look forward to an English translation of László Krasznahorkai’s novel. As a member of PEN, I was invited last year to suggest literary works for English translation. After I proposed Sátántangó and they published my response, I received a note from Barbara Epler of New Directions: “We are waiting on the delivery of its translation by the great George Szirtes, eagerly waiting, and will publish it as soon as we can. (We already have his translations of László’s The Melancholy of Resistance and War & War.)” So once it appears, I’ll no longer have to depend on the French translation by Joëlle Dufeuilly (2000) published by Gallimard, which I’ve owned for many years.

The film finally became available here last year on DVD from Facets Video, helping to demonstrate how much cinema as a “language” is more easily translatable than literature. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 24, 1993). — J.R.

LAST ACTION HERO

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by John McTiernan

Written by Shane Black, David Arnott, Zak Penn, and Adam Leff

With Arnold Schwarzenegger, Austin O’Brien, Charles Dance, Anthony Quinn, Tom Noonan, Mercedes Ruehl, F. Murray Abraham, and Robert Prosky.

The word is out: Last Action Hero is an unmitigated disaster. The sound of studio panic was plainly audible in a report in the June 17 New York Times that Columbia Pictures threatened to sever all communications with the Los Angeles Times if it didn’t guarantee it would “never again run a story written or reported by Jeff Wells about (or even mentioning) this studio, its executives, or its movies.” Wells’s crime was a June 6 article in the Los Angeles Times reporting that a test-marketing preview of Last Action Hero held in Pasadena about two weeks earlier had been disappointing. The article contained “categorical denials” from several studio executives that such a screening had ever taken place, but clearly this wasn’t enough for the industry people. As Wells told the New York Times, “You’re talking about a studio in a major meltdown mode. These guys are blitzing out here.”

I read this story only hours before seeing another “disappointing” preview of Last Action Hero in Chicago, after several weeks of hearing rumors that the picture was a “mess” and in deep, deep trouble. Read more

I wouldn’t call this a masterpiece, but it’s certainly honorable and original. I suspect that a major reason why Ari Folman’s animated nightmare has been picking up some sizable awards–best picture by the National Society of Film Critics, best foreign-language film at the Golden Globes–is that it does something that the mainstream U.S. news media more or less refuses to do. It allows the American public to express its disgust and horror for what’s currently happening in Gaza. In a similar way, albeit far more indirectly, roughly two year ago, Clint Eastwood’s Letters from Iwo Jima allowed many of us to cope a little better with some of our rage and sorrow about the occupation of Iraq. And as I noted at the time in my capsule review for that film, Waltz with Bashir also suggests that distinguishing between meaningful and senseless wars may be a civilian luxury. [1/12/09] Read more

From Cineaste, Vol. XXXIII, No. 4, 2008. -– J.R.

1) Has Internet criticism made a significant contribution to film culture? Does it tend to supplement print criticism or can it actually carve out critical terrain that is distinctive from traditional print criticism? Which Internet critics and bloggers do you read on a regular basis?

1) a. Significant and profound. Because the changes it has wrought are ongoing and unfolding, it’s still hard to have a comprehensive fix on them.

1) b. It can and does do both. By broadening the playing field in terms of players, methodologies, audiences, social formations, and outlets, it certainly expands the options. The interactivity of almost immediate feedback, the strengths and limitations of being able to post almost as quickly as one can think (or type), the relative ease of making screen grabs — these and many other aspects of Internet discourse are bringing about changes in content as well as in style and form, shape and size.

1) c. Here’s just a sample: To varying degrees (some much more regularly than others), I like to read Acquarello, David Bordwell, Zach Campbell, Fred Camper, Roger Ebert, Flavia de la Fuente, Filipe Furtado, Michael E. Read more

This appeared in the November 15, 1991 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

VIDEOS BY SADIE BENNING

“I would like to call this new age of cinema the age of the caméra-stylo [camera-pen],” Alexandre Astruc wrote prophetically in 1948 in the journal Écran français. “This metaphor has a very precise sense. By it I mean that the cinema will gradually break free from the tyranny of what is visual, from the image for its own sake, from the immediate and concrete demands of the narrative, to become a means of writing just as flexible and as subtle as written language . . .

“It must be understood that up to now the cinema has been nothing more than a show. This is due to the basic fact that all films are projected in an auditorium. But with the development of 16-millimeter and television, the day is not far off when everyone will possess a projector, will go to the local bookstore and hire films written on any subject, of any form, from literary criticism and novels to mathematics, history, and general science. From that moment on, it will no longer be possible to speak of the cinema. Read more

Posted on the web site Wellesnet. I’ve added a few illustrations of my own to the original, conducted by Lawrence French.

Having worked as a consultant on the completion of The Other Side of the Wind, I’m no longer sure that all my comments about the film found below would still hold. — J.R.

Jonathan Rosenbaum has long been an astute critic on the cinema of Orson Welles, frequently writing about Welles’ films. He served as the consultant for the re-edited version of TOUCH OF EVIL, and edited THIS IS ORSON WELLES, the seminal book of Welles interviews, conducted by Peter Bogdanovich.

The following interview has been combined from two separate conversations. The first took place in the fall of 1998, after the release of the re-edited version of TOUCH OF EVIL, and focused on the problems inherent in changing TOUCH OF EVIL to what Welles requested in a memo written 41 years earlier. The second interview occurred in January, 2003, and covers Welles’ two

LAWRENCE FRENCH: Does the film museum in Munich now have most of the unfinished Welles films? Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 1, 1994). — J.R.

One of the delightful things about Rose Troche’s stylish, low-budget, filmed-in-Chicago black-and-white lesbian comedy is that its characters all register as real people, even when bits of the dialogue are stiff or some of the lip sync is off; this isn’t a movie about lesbians, it’s a movie about these lesbians, and we’re likely to think of them afterward as if they were people we knew. As in the better American underground movies of the 60s, which this sometimes resembles, the youthfulness and the footloose free spirit — evident in everything from the performances and Ann T. Rossetti’s shooting style to Brendan Dolan and Jennifer Sharpe’s jazz score and the breezy rhythmic stretches bridging narrative sequences — keep things bouncing along like a clear spring day. (And though the characters themselves vary in age, there’s a clear note of shared adolescent braggadocio in the way that sex and romance here become real only after they’re talked about and described.) Written as well as produced by Troche in collaboration with Guinevere Turner, the younger of the two romantic leads (the other is V.S. Brodie), this movie dives into fantasy and stylized internal monologues with the same aplomb it brings to the buildup to a hot date. Read more

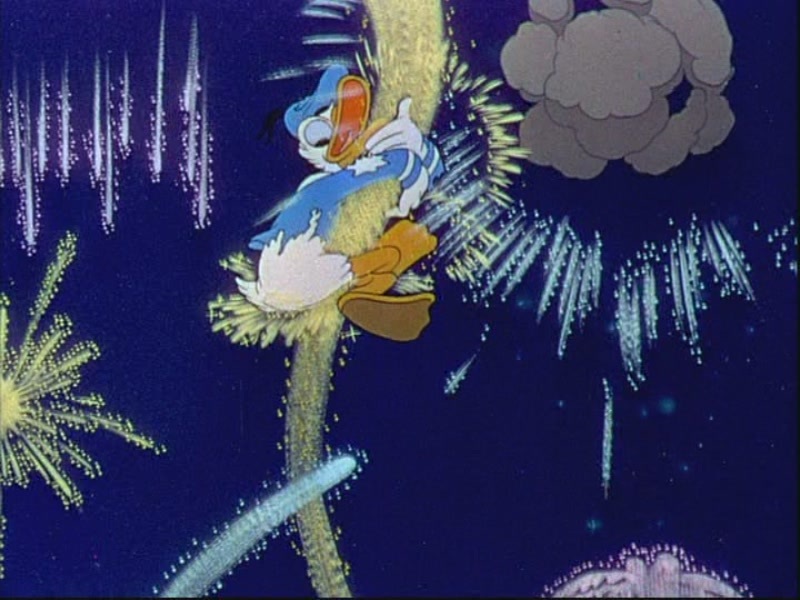

Written for The Unquiet American: Transgressive Comedies from the U.S., a catalogue/ collection put together to accompany a film series at the Austrian Filmmuseum and the Viennale in Autumn 2009. — J.R.

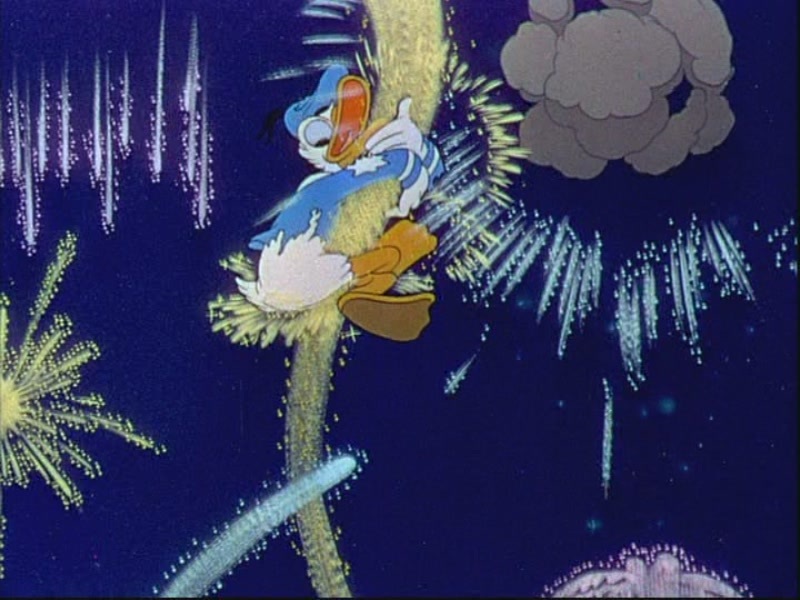

After Orson Welles tried to implement Nelson Rockefeller’s

Good Neighbor policy with South America

in an unfinished episodic film, It’s All True (1942),

scandalizing both RKO and Latin American dignitaries

by focusing on poor and nonwhite characters,

Walt Disney dutifully offered a more conventionally

touristic and clearly segregated view of the

Continent, and succeeded spectacularly with the

same studio and many of the same dignitaries (as well

as with general audiences in both the U.S. and South

America) by offering this kitschy and visually extravagant

episodic, 70-minute film (1945), his first feature

to combine animation with live action. The title

pals are the infantile Donald Duck playing an American

tourist and the somewhat older Brazilian parrot

Joe Carioca and Mexican rooster Panchito, the latter

two playing Donald’s principal tour guides. The film

begins somewhat conventionally with tales about

Pablo, a South Pole penguin longing for warmer surroundings

who sails up the coast of Chile and Peru,

and a Uruguay boy gaucho who enters a flying donkey

in a race. Read more