What dispiriting news, to learn of Raúl Ruiz’s death at age 70 upon waking today [in August 2011], just after receiving the Portuguese DVD box set of his extraordinary Mysteries of Lisbon yesterday and watching the first half of it last night. I knew, of course, that his health had been very poor, so this wasn’t entirely a shock. But it’s clearly a major loss. (A curious coincidence: Raúl lived the same number of years as the filmmaker he admired the most, Orson Welles.)

We had been friends for a time, then drew apart — mainly, I suspect, because he became a little fed up with my inability to speak and understand French more fluently. But I’m very grateful for the many hours we were able to spend together, including one opportunity I had to appreciate what an excellent cook he was. (For an excellent memoir about him, as well as one of the best appreciations of Ruiz that I know — even though I disagree with its premise that Klimt qualifies as a biopic [at least in its original, longer, and better version], and Raúl himself disagreed with the premise that Three Lives and Only One Death was one of his best films — check out Adrian Martin’s “A Ghost at Noon” at http://www.filmcritic.com.au/essays/ruiz.html.)

Read more

From the Summer 2019 issue of Cinema Scope. — J.R.

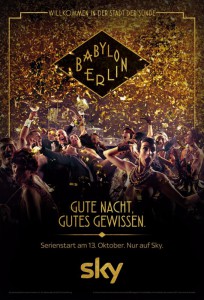

Readers of Movie Mutations, the 2003 collection I co-edited with Adrian Martin, will know that the Jungian notion of global synchronicity has long been a preoccupation of mine. One striking recent manifestation of this phenomenon came to light when I read, around the same time, Mark Peranson’s editor’s note about Documentary Now! in the last issue of this magazine, and a ramble from David Thomson about binge-watching TV in the April Sight & Sound, both of which compelled me to finally take out a trial subscription to Netflix and spend the better part of a weekend binge-watching Series One and Two of Babylon Berlin (12 hours) and the even more absorbing Russian Doll(four hours) via streaming — just before receiving a four-disc PAL DVD box set of the former from Acorn Media International on Monday. All of which suggests that Mark, D.T., Acorn, and I have mysteriously been on roughly the same market wavelengths regardless of our illusions of free choice.

There’s a real danger that streaming may eventually make the name of this column anachronistic, so for the time being please allow me to include that viewing option, as I’ve already done with Blu-rays. Read more

From Cineaste 22, no. 3, 1996; reprinted with further comments in Discovering Orson Welles. — J.R.

Biographies of Orson Welles reviewed in this article:

Orson Welles: The Road to Xanadu, by Simon Callow (New York: Viking, 1995). 640 pp.

Rosebud: The Story of Orson Welles, by David Thomson (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1996). 461 pp.

Orson Welles, revised and expanded edition, by Joseph McBride (New York: Da Capo, 1996). 243 pp.

Two prevailing and diametrically opposed attitudes seem to dictate the way most people currently think about Orson Welles. One attitude, predominantly American, sees his life and career chiefly in terms of failure and regards the key question to be why he never lived up to his promise — “his promise” almost invariably being tied up with the achievement of Citizen Kane. Broadly speaking, this position can be compared to that of the investigative reporter Thompson’s editor in Citizen Kane, bent on finding a single formula for explaining a man’s life. The other attitude — less monolithic and less tied to any particular nationality, or to the expectations aroused by any single work — views his life and career more sympathetically as well as inquisitively; this position corresponds more closely to Thompson’s near the end of kane when he says, “I don’t think any word can explain a man’s life.” Read more

Published under a different title in the online Barnes and Noble Review (May 18, 2010). — J.R.

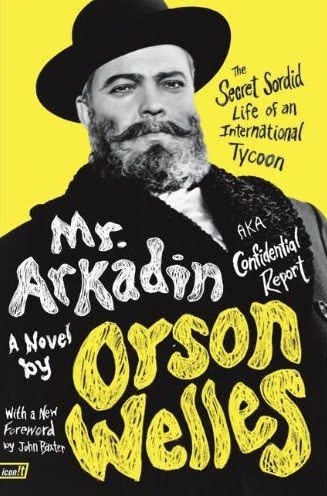

John Baxter’s new Foreword to the 1956 novelization of Orson Welles’s Mr. Arkadin, aptly called “No Pilot Known,” correctly discloses on its penultimate page that the novel was actually written in French by one Maurice Bessy, who adapted Welles’s original screenplay. This fact is verified by the recent recovery in France of the correspondence between Welles and Arkadin’s producer, Louis Dolivet. But none of this has prevented the novel’s latest edition, like all the previous ones, from trumpeting the name of Orson Welles as sole author on its cover.

This should come as no surprise. How can a publisher expect to sell the uncredited English translation of a French novelization of an unfinished film, especially if the novel was written by a forgotten film critic? For starters, it has to assume, contrary to Welles, that the film is (or was) finished. This is also why the Criterion box set, released in 2006, insists on calling itself The Complete Mr. Arkadin, even though Welles wasn’t able to complete any single version of it.

The task of rationalizing Welles’s idiosyncratic working methods and fractured film career in consumerist, marketplace terms has invariably led to many obfuscations. Read more

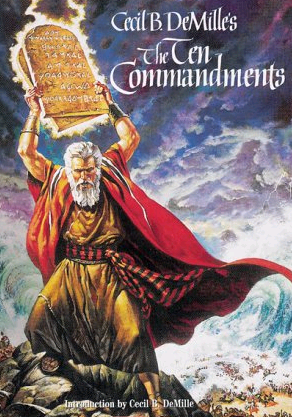

This appeared in the April 6, 1990 issue of the Chicago Reader. Although my favorite Cecil B. De Mille film is the talkie version of Dynamite (1929) — I still haven’t seen the silent version, released around the same time — The Ten Commandments (1956) is probably the film of his that I’m most familiar with, along with the somewhat underrated Samson and Delilah (1949).

Part of what’s so remarkable about the scandalously underrated and neglected Dynamite [see still, above] is how real and serious it contrives to make the marital pairing of a coal miner (Charles Bickford) and a spoiled city heiress (Kay Johnson), even though brought about through preposterous plot contrivances, and how, in spite of De Mille’s conservative social and political biases, it assigns equal amounts of dignity and vulnerability to both classes. It’s also one of the most suspenseful and charged melodramas to have ever come out of Hollywood. — J.R.

The Power of Belief

THE TEN COMMANDMENTS

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Cecil B. De Mille

Written by Aeneas Mackenzie, Jessie L. Lasky Jr., Jack Gariss, and Frederic M. Frank

With Charlton Heston, Yul Brynner, Anne Baxter, Edward G. Robinson, Yvonne De Carlo, Debra Paget, John Derek, Cedric Hardwicke, and Vincent Price. Read more

I’m sorry that the Chicago Reader in its current issue chooses not to acknowledge that it’s anything special or worthy of more than cursory notice, but Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day is probably the greatest Taiwanese film ever made, and it doesn’t turn up here often. Doc Films is showing it at 7 pm. Here’s my original capsule review, only slightly updated:

Bearing in mind Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy, this astonishing 230-minute epic (1991) by Edward Yang (1947-2007), set over one Taipei school year in the early 60s, would fully warrant the subtitle “A Taiwanese Tragedy.” A powerful statement from Yang’s generation about what it means to be Taiwanese, superior even to his later masterpiece (and final film) Yi Yi (2000), it has a novelistic richness of character, setting, and milieu unmatched by any other 90s film (a richness only partially apparent in its three-hour version). What Yang does with objects — a flashlight, a radio, a tape recorder, a Japanese sword — resonates more deeply than what most directors do with characters, because along with an uncommon understanding of and sympathy for teenagers Yang has an exquisite eye for the troubled universe they inhabit. This is a film about alienated identities in a country undergoing a profound existential crisis — a Rebel Without a Cause with much of the same nocturnal lyricism and cosmic despair. Read more

From the September 13, 1996 issue of the Chicago Reader. This film was probably the most popular of the dozen features I showed to MA students in my World Cinema Workshop at Film.Factory in Sarajevo (September 15-19, 2014). — J.R.

The Asthenic Syndrome

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Kira Muratova

Written by Sergei Popov, Alexander Chernych, and Muratova

With Popov, Olga Antonova, Natalya Busko, Galina Sachurdaewa, Alexandra Ovenskaya, and Natalya Rallewa.

Every time I am asked what the film is about, I reply, quite honestly, “It’s about everything.” — Kira Muratova, 1990

Seven years have passed since I first saw Kira Muratova’s awesome The Asthenic Syndrome at the Toronto film festival, and while waiting for it to find its way to Chicago I’ve had plenty of time to speculate about why a movie of such importance should be so hard for us to see. Insofar as movies function as newspapers, this one has more to say about the state of the world in the past decade than any other new film I’ve seen during the same period, though what it has to say isn’t pretty. So maybe the reason it’s entitled to only one local screening — at the Film Center this Sunday — is the movie business’s perception that it must offer only pretty pictures. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 21, 1997). It’s worth noting that Japanese doesn’t distinguish between singular and plural, so that the film is also known as The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum, which is an equally accurate translation. — J. R.

Though not the best known of Kenji Mizoguchi’s period masterpieces, this 1939 feature is conceivably the greatest. (For me the only other contender is Sansho the Bailiff.) The plot, which oddly resembles that of There’s No Business Like Show Business, concerns the rebellious son of a theatrical family devoted to Kabuki who leaves home for many years, perfects his art, aided by a working-class woman who loves him, and eventually returns. Apart from the highly charged and adroitly edited Kabuki sequences, the film is mainly constructed in extremely long takes, and an intricate rhyme structure between two time periods is developed by matching camera angles in the same locations. Never before or since (apart from The 47 Ronin) has Mizoguchi’s refusal to use close-ups been more telling, and the theme of female sacrifice that informs most of his major works is given a singular resonance and complexity here. Demonstrating an uncanny mastery of framing and camera movement, the film also has a complexity of characterization that’s shown with sublime economy. Read more

From Cinema Scope #46 (Spring 2011). — J.R.

Underneath the Persian credits, over heavy metal music, the camera roams around inside a colour photograph, grazing over pointillist surfaces and male faces — finally pulling back to reveal the Islamic Revolution Guard Corps in 1983, getting ready to drive their motorcycles over a huge replica of the American flag on the pavement in front of them. Cut to black and the film’s title, The Hunter.

Cut to a highway tunnel, then to a rifle being loaded in the woods, then to the same title hero (played by the writer-director, Rafi Pitts) holding the rifle in front of a raging campfire at night. Cut to an overhead shot of a busy Tehran freeway — then to a sinister carwash that seems to be located in the general vicinity of Hell, smoky fumes rising from the spray. And finally to the hero being told by a potential employer that as a convict he doesn’t qualify for a day job, he has to take the night shift. But as we discover a little later, his wife Sara already has a day job, meaning that when he takes the night watchman job, he’ll have little time to spend with her and their six-year-old daughter. Read more

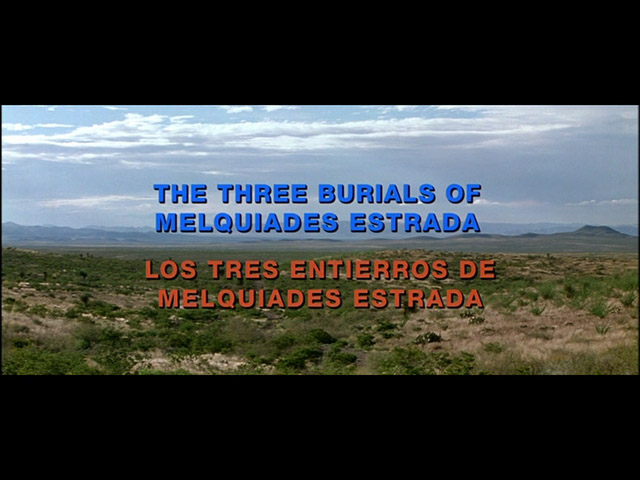

This appeared in the Chicago Reader‘s February 3, 2006 issue. Tommy Lee Jones’ subsequent feature, The Homesman, confirms the talent, originality, and boldness of Jones as a director, even if it may also come across at certain junctures as less lucid than its predecessor. — J.R.

The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Tommy Lee Jones

Written bu Guillermo Arriaga

With Jones, Barry Pepper, Julio Cesar Cedillo, Dwight Yoakam, January Jones, and Melissa Leo

At last year’s Cannes film festival, The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada walked off with the prizes for best actor (Tommy Lee Jones) and best screenplay (Guillermo Arriaga). It’s often hard to disentangle story, acting, and direction when they’re working together as well as they are here, but I would have honored Jones for his direction. That prize went to Michael Haneke for Caché, his eighth theatrical feature. This is Jones’s first, though he directed (and cowrote and starred in) a made-for-TV western, the 1995 The Good Old Boys.

Both Haneke’s and Jones’s films are political. The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada, a western, protests the abusive treatment of Mexican immigrants in west Texas, and Caché, an anxiety-ridden crime thriller, protests the abusive treatment of Algerians in France. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 1, 1991). — J.R.

Terrence McNally’s two-character play Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune is about an embittered coffee shop waitress, the victim of rape by her father, who reluctantly succumbs to the advances of a much younger short-order cook fresh out of prison. Leave it to producer-director Garry Marshall, who brought us Pretty Woman, to Hollywoodize this grim scenario to the point of incoherence (with a script by McNally himself), casting Michelle Pfeiffer as the waitress and Al Pacino as the (now older) short-order cook, and substituting wife-beating for incestuous rape. To their credit, the filmmakers do a fair job of depicting the workings of a Manhattan coffee shop (despite some unnecessary cruelty involving one of the other waitresses), but not even the usually resourceful leads can overcome the missing or muddled motivations when it comes to the romance. Marshall only makes things worse by socking us with protracted, meaningful close-ups and punchy Marvin Hamlisch music meant to paper over the gaps. With Hector Elizondo (quite effective) and Kate Nelligan (painfully miscast) (1991). (JR) Read more

Cinema. Film Study. What a pity that the left hand rarely knows what the right hand is doing, and vice versa.

Thanks to the generosity of Girish Shambu, I’m the happy owner of a copy of Timothy Barnard’s retranslated, reselected, and annotated edition of André Bazin’s What is Cinema?, recently published in a handsome hardcover by www.caboosebooks.com, based in Montreal, with Varvara Stepanova’s 1922 woodcut of Charlie Chaplin, Sharlo Takes a Bow, gracing the cover.

First, here is the selection: “Ontology of the Photographic Image,” “The Myth of Total Cinema,” “On Jean Painlevé” (a short fragment that Barnard has translated for the first time), “An Introduction to the Charlie Chaplin Persona,” “Monsieur Hulot and Time,” “William Wyler, the Jansenist of Mise en Scène,” “Editing Prohibited,” “The Evolution of Film Language,” “For an Impure Cinema: In Defense of Adaptation,” “Diary of a Country Priest and the Robert Bresson Style,” “Theatre and Film (1),” “Theatre and Film (2),” and “Cinematic Realism and the Italian School of the Liberation”.

Regrettably, the 354-page book, with a ten-page Publisher’s Foreword, the aforementioned 13 essays by Bazin, 61 pages of helpful annotation, a combined 19-page Glossary of Films and Film Title Index, and a six-page Index of Names, is unavailable to most people outside of Canada, and for legal reasons, including copyright laws, you can’t even order this from Canadian Amazon. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 26, 2001). — J.R.

Waking Life

****

Directed and written by Richard Linklater.

The cinema is an antiuniverse where reality is born out of a sum of unrealities. –Jean Epstein

I must have come across this statement by Epstein, a French theorist and filmmaker (1897-1953), in the late 60s or early 70s, but I no longer remember where. I’ve scanned his writings on several occasions since, but I haven’t found the quote. Sometimes I wonder if I read or heard about it in a dream — making it one of the unrealities Epstein is referring to.

Wherever the quote comes from, it applies beautifully to the animated feature by Richard Linklater that premiered at Sundance early this year and is currently playing at the Music Box. The movie is a string of paradoxes and reflections about what’s real and what’s not, about when you’re dreaming and when you’re awake, and the unusual way it’s put together seems calculated to complicate all of the issues it raises rather than resolve any of them. Over 25 days Linklater, one of his coproducers, and a sound person shot a first version of everything we see in this movie with two relatively low-tech digital video cameras in and around Austin and in San Antonio and New York — basically taping a lot of people talking and walking, as well as listening and sitting. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 2, 2000).

On October 5, 2014, I had the pleasure of introducing The Sandwich Man at the Museum of the Moving Image’s exhaustive Hou retrospective in Astoria. My late friend Gilberto Perez came to the screening and we had dinner afterwards; it was the last time I ever saw him. — J.R.

Films by Hou Hsiao-hsien

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful about what we pretend to be. — Kurt Vonnegut Jr., Mother Night

How significant is it that neither of the two greatest working narrative filmmakers is fluent in English? Not very. But it might be logical. After all, most of the people in the world, including those in Iran and Taiwan, don’t speak English, even though that places them, in American eyes, in the margins, outside even the on-line global culture.

If being in the margins means being in the majority, it stands to reason that Abbas Kiarostami and Hou Hsiao-hsien, as chroniclers of what’s happening on the planet at the moment, should both be poet laureates of the sticks — though they don’t have much in common beyond a taste for filming in long shot, pioneering direct sound recording in their national cinemas (in both cases to honor the speech patterns of nonprofessional actors), and a general sense of philosophical detachment. Read more

The further adventures of Marty McFly (Michael J. Fox) and Doc Emmett Brown (Christopher Lloyd) take them from 1985 to 2015 and back, and then back to 1955 after a mishap in the future involving the villain (Thomas F. Wilson) creates a universe parallel to the one they left. The problem with all the time-travel high jinks, involving multiple versions of the major characters (a gimmick that Robert Heinlein handled much better in stories like By His Bootstraps and All You Zombies), is that in order to make the plot even semiintelligible, writer Bob Gale and director-cowriter Robert Zemeckis have to turn all these characters into strident geeks and make the frenetic action strictly formulaic. (Significantly, the principal romantic interest, Elisabeth Shue, is knocked unconscious early on so she won’t interfere with the little-boy games, and Fox briefly playing his own sister in drag only adds to the rampant misogyny.) There’s a bit of fun in the 2015 section (although this notion of the future is more nostalgic and Disneyfied than genuinely speculative), but the shrill simplicities that follow become increasingly mechanical. By the end, you may feel that you’ve just sat through a feature-length commercial for both part one (which has to be seen to make this sequel comprehensible) and part three (a trailer for it literally ends part two), along with a host of other consumables (from Pepsi to other Spielberg productions), and have been turned into a first-class geek along with the charactersan airhead consumer designed to wolf these products down. Read more