From Sight and Sound (Autumn 1972). I like the recent second edition of this a lot more — enough to have given it a blurb that’s used in the ads, and not only because Schrader cites me in his new introduction about “slow films”. — J.R.

TRANSCENDENTAL STYLE IN FILM: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer

By Paul Schrader

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS, $10.00

Modesty and caution are not exactly what one expects to find in a book with this title, on these three directors; but ironically, one of the chief limitations of this comparative study is that these qualities often seem to predominate over everything else. The first ‘step’ of transcendental style,for instance, is defined as follows: ‘The everyday: a, meticulous representation of the dull, banal commonplaces of everyday living’ or what [Amédée] Ayfre quotes Jean Bazaine as calling “le quotidien”.’ Not quite a double redundancy, but close enough to make one wonder why this passage and so many comparable ones suggest a critic walking on eggshells.

Although it is nowhere identified as such, Schrader’s extended essay has much of the look, shape and sound of a doctoral dissertation [2013 note: I believe that this was in fact a Masters’ thesis]. 194 footnotes are appended to 169 pages of text, and each step of the argument proceeds like a slow-motion exercise in which every inch of terrain must be defined and tested before it can be touched upon. For starters, the definitions of ‘transcendental’ and ‘style’ take up nearly two pages apiece.

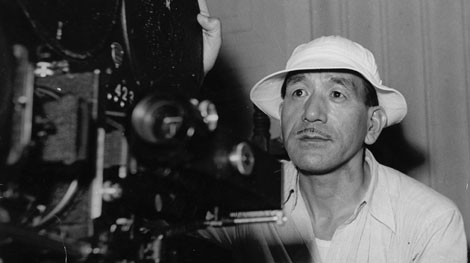

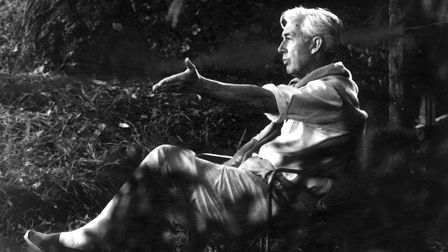

To a certain extent, such circumspection is admirable. Schrader rightly points out in his introduction that ‘transcendental’ is an imprecise, much-abused term in film criticism, and the precise definition he gives it here makes the concept functional rather than loosely evocative. The central theme derives from an epigram by Gerardus van der Leeuw: ‘Religion and art are parallel lines which intersect only at infinity, and meet in God.’ Relating the separate styles of Ozu and Bresson to a common spiritual process, Schrader works overtime in making this assumption appear tenable. His conclusion: that ‘the family-office cycle of Ozu’s later films and the prison cycle of Bresson’s middle films’ construct a similar style to express the Transcendent’, while Dreyer’s films exhibit this style only partially, in interaction with the conflicting influences of Kammerspiel and expressionism. With varying degrees of plausibility, Ozu is related to the Zen arts of painting, gardening and haiku; Bresson to Jansenist theology, Byzantine portraiture and the aesthetics of Scholasticism; Dreyer to Gothic architecture.

If the Dreyer chapter comes off best, this may be because the director is accorded an impure status (along with Rossellini, Antonioni, Michael Snow and Budd Boetticher, among others, who are segregated to passing references), and thus registers as recognisably human. Here and in a recent article on another impure subject (‘Notes on Film Noir’, FILM COMMENT, Spring 1972), Schrader shows himself particularly adept at charting complex relationships without diminishing the singularity of separate films.

Confronting Ozu and Bresson, he comes rather close to converting them into matching icons in a high-priced auction. (‘No artist or style has cornered the transcendental market,’ he remarks at one point, in an unfortunate attempt to lighten his academic prose.) Discussing each director, he relies excessively on pre-existing models provided by other critics: Donald Richie dominates the Ozu section, while the observations on Bresson are frequently nothing more than extended glosses and refinements of Ayfre, Bazin and Sontag. If his underlying thesis seems to limit the range of both directors, this may be partially due to the fact that too much of the visible work comes from the library; evidence from the screen is almost made to seem secondary.

As Schrader makes clear in his conclusion, his ‘intention is not to pretend any “new” aesthetics, but rather to situate [his] concept of filmic “transcendental style” within some previous theories.’ But the net effect of this synthesis is to turn Bresson and Ozu into postulates, often reducing their films to simple cause-and-effect mechanisms. In Ozu, ‘a shot of snow-capped mountains inserted after a discussion by several parents plainly suggests the unity to which they aspire, but the same shot inserted after a parent-child quarrel suggests that the traditional unity may have little meaning within the post-war family structure.’

Bresson’s use of techniques from Byzantine art is said to ‘produce certain desired, tried-and-true audience reactions’ — as if he were following mail-order recipes – and we are told that he ‘shoots his scenes from one unvarying height…at the chest level of a standing person,’ a fact contradicted by at least half a dozen stills reproduced in the book. Despite such difficulties, we are persuaded that Ozu and Bresson have many stylistic traits in common; yet by the time we’ve finished this heavy entertainment, we may well suspect that the differences between these master directors might be even more important.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM