Now that I’ve seen three of the most recent half-dozen features of Jon Jost — Coming to Terms (2013, Butte, Montana), Blue Strait (2014, Port Angeles, Washington), and They Had it Coming: True Gentry County Stories (2015, Stanberry, Missouri), in that order — I find myself, unlike certain others (including Jost himself), preferring the third to the second and the second to the first. The reason why is that the basic theme of Jost’s narrative films for quite some time has been the tragic story of American men, some of them patriarchal, others simply burnt-out cases, losing their all-American souls — a theme that to my mind he already gave near-perfect expression to in his 1977 Last Chants for a Slow Dance (dead end) and which he has been spinning out periodically in diverse variations ever since. But to judge from the developments between these three recent features, this may be a story that Jost may finally be turning away from — for the sake of non-narrative meditations (especially in much of Blue Strait) and the stories of others (as in They Had it Coming), others whom in some cases may not even have discernible souls to lose. And for me, these are positive developments for a prodigious independent artist whose productivity is so difficult to chart that his eight separate blogs and two separate web sites make it even harder to track in its various forms and dispersals. (Significantly, the only serious flaw for me in Blue Strait, which charts the breakup of a gay couple, is a sequence that suggests the subsequent suicide of one of the men—a conclusion that has come to seem almost obligatory in Jostland, and which I’m happy to report that Jost himself is thinking about removing.)

I don’t mean to suggest by this that the characters delivering monologues in They Had it Coming — cowritten by Blake Eckard, one of the actors — or the small-town American landscapes that Jost frames so well are dehumanized and soulless, only that they’re too ordinary, familiar, and even archetypal to wear their hearts or souls on their sleeves, and that they come closer to belonging to what Manny Farber has called termite art than to the relative bluster of white elephant art. Even the negativity of the first of the characters, a quietly mordant woman, has a resonance that we immediately recognize as part of our contemporary zeitgeist: “There’s almost nothing that I hate more than a happy person tryin’ to get me on that train — making you as happy as they are. No thank you.”

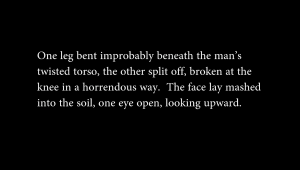

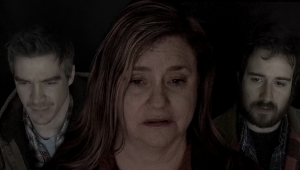

Similarly, the various stories, even at their most mindlessly repetitive and cadenced, seem to circle endlessly around the facts and matter-of-factness of death. What I like especially about They Had it Coming is the literary quality of this gab, which makes me think of such monologue collections as Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River Anthology (1915), William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying (1930), and William March’s Company K (1933), all three of which are equally concerned with death. Perhaps significantly, the only monologue in the film that takes an actual literary form, by appearing in printed intertitles (and which eventually becomes “dramatized” and illustrated, much later in the film), is about how to dispose of a corpse in the woods and what it looks like:

Jost himself is a kind of monologuist as well as a landscape artist, so one might say that the monologue form seems to liberate him — even when it comes to tripling his verbal monologues and tripling what one might call his visual/ landscape “monologues” within separate shots. [3/10/2018]