Here are three of the 40-odd short pieces I wrote for Chris Fujiwara’s excellent, 800-page volume Defining Moments in Movies (London: Cassell, 2007). Each one of these entries devoted to “scenes” has something to do with imaginatively combining animation with live-action. — J.R.

***

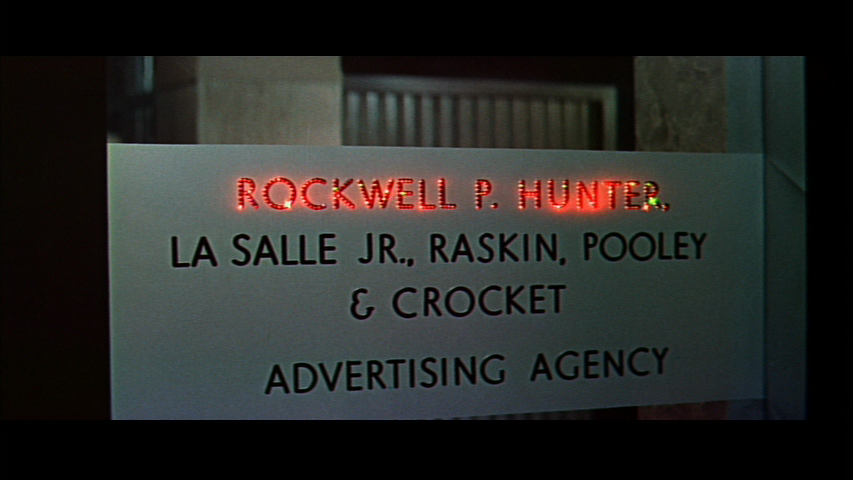

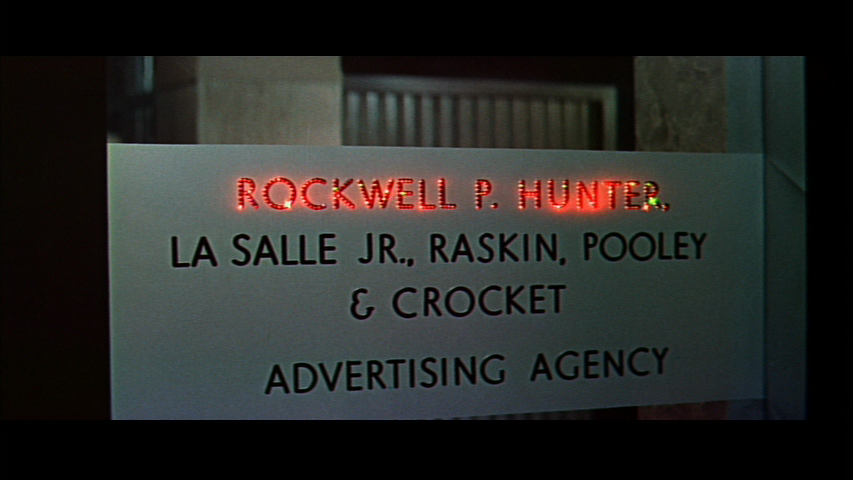

1957 / Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? –– Rock Hunter dances through his empty office at night to an offscreen chorus (“Mr. Successful, You’ve Got it Made”).

U.S. Director: Frank Tashlin. Cast: Tony Randall.

Why It’s Key: In a key satire of the 50s, a Hollywood dream overtly springs to life inside a Hollywood dream.

Madison Avenue adman Rockwell P. Hunter (Tony Randall) signs movie star Rita Marlowe (Jayne Mansfield) to endorse Stay-Put lipstick, thereby making his company a fortune and eventually turning him into first a first a vice president at the ad agency with a key to the executive washroom, then the new president. Before long, even though his alienated fiancée has broken off with him in disgust, he’s clearly “got it made” —- a phrase that he and this movie keep repeating so many times, in so many different ways, like a desperate mantra, that it begins to sound increasingly sinister. Perhaps the most pertinent gloss on this is offered to him by the company’s former president (John Williams), who has meanwhile happily left advertising for horticulture and offers his gloss as a kind of warning: “Success will fit you like a shroud.” Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 27, 2004). — J.R.

A newly appointed homicide detective in San Francisco (Ashley Judd) tracks a serial killer whose victims are all men she has slept with. Director Philip Kaufman, who usually writes his own scripts, works with a cliche-ridden screenplay by Sarah Thorp, and his personal touches mainly seem to consist of selecting fashionable North Beach bars as locations. His usual flair for erotic detail largely deserts him here, and this thriller seems most interested in lingering over battered and bloodied male faces. Samuel L. Jackson and Andy Garcia costar. R, 97 min.

Read more

Read more

From the November 4, 2005 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

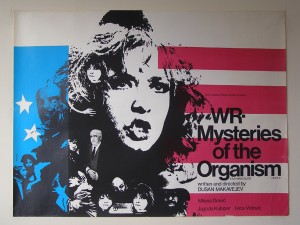

We may forget that the most radical rethinking of Marx and Freud found in European cinema of the late 60s and early 70s came from the east rather than the west. Indeed, it’s hard to think of a headier mix of fiction and nonfiction, or sex and politics, than this brilliant 1971 Yugoslav feature by Dusan Makavejev, which juxtaposes a bold Serbian narrative shot in 35-millimeter with funky New York street theater and documentary shot in 16. The WR is controversial sexual theorist Wilhelm Reich and the mysteries involve Joseph Stalin as an erotic figure in propaganda movies, Tuli Kupferberg of the Fugs killing for peace as he runs around New York City with a phony gun, and drag queen Jackie Curtis and plaster caster Nancy Godfrey pursuing their own versions of sexual freedom. In English and subtitled Serbo-Croatian. NC-17, 85 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 2, 2004). This wonderful documentary, incidentally, is now available on the Criterion DVD of Pickpocket. One of its most fascinating paradoxes for me is that Mangolte, a friend, isn’t a religious person, but this documentary strikes me as profoundly spiritual; Lasalle’s home is even treated as a sacred shrine. — J.R.

Les modèles de “Pickpocket”

***

Directed and written by Babette Mangolte

With Pierre Leymarie, Marika Green, and Martin Lasalle.

Not until he was in his late 90s did Robert Bresson get the recognition he deserved. He died in 1999 at the age of 98, living long enough to see his work affirmed by a retrospective the Toronto Cinematheque’s James Quandt organized that traveled around the world to full houses.

For years mainstream critics regarded Bresson as esoteric, pretentious, even something of a joke. “The chief fault is that the hero is a vacancy, not a character,” wrote Stanley Kauffmann in one of the more sympathetic reviews of Bresson’s 1959 Pickpocket, a free adaptation of Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment. “Martin Lasalle, who plays the part, has a bony, sensitive face, but no deader pan has crossed the screen since Buster Keaton. The besetting fallacy of modern French films and novels is the belief that nullity equals malaise and/or profundity.” Read more

From the May 14, 2004 Chicago Reader. P.S. I once went to hear Cecil Taylor at a San Francisco club in the 1980s with Nathaniel Mackey (as well as Trinh T. Minh-ha and the late Bell Hooks).- J. R.

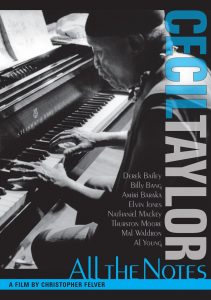

Any musician of Cecil Taylor’s caliber deserves sustained attention, but the jazz great doesn’t get it in this rambling assortment of alternating sound and music bites. Taylor is a nonstop pontificator of varying interest as well as a brilliant and virtuosic avant-garde pianist, but director Christopher Felver treats his music and his remarks as equally relevant, cutting between them — or away to still photographs — as if determined not to focus too long on any one thing. On piano Taylor employs an idiosyncratic technique, sometimes using his elbows as well as his fingers, and I’d hoped the camera angles would reveal this; apart from a brief shot behind the final credits, however, Felver shows almost everything except the keyboard. At least the other talking heads have things to say, including Elvin Jones, Amiri Baraka, Nathaniel Mackey, and Al Young. 71 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From The Guardian, August 27, 2004, where this appeared under the title “Independence Day”. — J.R.

It’s an enduring and endearing paradox of Jim Jarmusch’s art as a writer-director that even though it may initially come across as a triumph of style over content, it arguably turns out to be a victory of content over style. The humanism of this mannerist winds up counting for more than all his stylistic tics, thus implying that his manner may simply be the shortest distance between two points.

Maybe it’s the ultimate paradox of minimalism: the less your work does and is, the more these things matter. In Jarmusch’s case, this partially means that the very notions of hipness and independence that originally defined his stylish filmmaking in the 80s — with Permanent Vacation (1980), Stranger Than Paradise (1984) Down by Law (1986), and Mystery Train (1989) — started working against his public profile in the 90s, especially once being outside the mainstream started being regarded with greater suspicion.

Furthermore, around the time of Jarmusch’s Night on Earth (1992), released the same year as Reservoir Dogs, hipness and independence as values within American culture had both become somewhat muddled and coarsened in the process of becoming mainstreamed. Read more

The following article appeared in the February 23, 1990 issue of the Chicago Reader. –J.R.

ART OF MUSIC VIDEO

For people like myself who have conflicted feelings about music videos as an art form, the four-part series Art of Music Video — playing for the second time at the Film Center this weekend — offers lots of material to consider. Even so, this presentation of a hundred videos assembled by Michael Nash of the Long Beach Museum of Art involves a number of curatorial decisions that I have problems with. Before considering the videos themselves, let me list these problems; some of them are overlapping rather than consecutive, but putting them in list form will help to give some idea of how many boats this particular series is missing:

(1) Historical. Although Nash’s selection is media-specific—that is, generally limited to videos—one of his four programs, “Vanguard Re-visions,” has a subcategory called “Experimental Film: Invention and Intervention,” consisting of films made by Bruce Conner, James Herbert, and Jem Cohen between 1961 and 1989.

While I have no quarrel with the inclusion of these figures, it’s clear that this attempt to give a foreshortened art-history perspective rules out a lot more of the history of music videos and their precursors than it includes. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 22, 1992). — J.R.

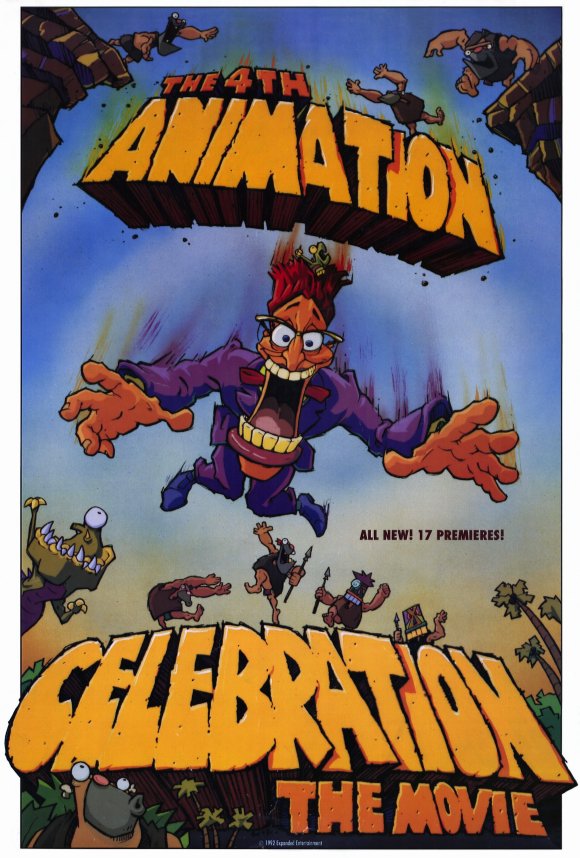

THE 4TH ANIMATION CELEBRATION: THE MOVIE

*** (A must-see)

Finding out what’s happening in the world these days is no easy matter. Turn to a newspaper and we may learn what American business wants to know — or thinks it wants to know — but not much else; check out what’s on TV and chances are that the state of the world will get less attention than the current Hollywood releases. Even when there is expanded coverage we often can’t be sure that the journalists understand what they’re reporting or that what they’re saying encompasses all that they understand.

I suppose this has always been true to some extent, and maybe it only seems worse nowadays because we no longer have newsreels. Recently some fascinating “March of Time” shorts have come out on video — newsreel “essays” produced by Time-Life and released in movie theaters by Twentieth Century-Fox in the 30s, 40s, and 50s. What seems most quaint and touching about them is how easily people (both famous and ordinary) were induced by the camera to play fictional versions of themselves that they and everyone else were persuaded to think of as real. Read more

From The Movie, Chapter 33 (1980). -– J.R.

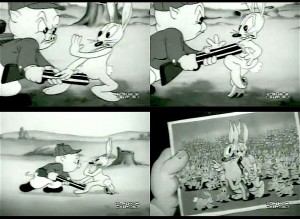

It was in 1940 that a brisk, buck-toothed city rabbit first sank teeth into carrot. briefly paused, gazed with indifferent aplomb at a lisping country rabbit-hunter with a shotgun and coolly inquired: ‘What’s up, Doc?’ This official debut of Bugs Bunny occurred at the beginning of A Wild Hare, one of nine cartoons that were supervised that year by Fred (known as ‘Tex’) Avery, a brilliant animator from Dallas who was working for Warner Brothers. The cartoon won an Academy Award nomination and the durable comedy team of Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd promptly went into business.

‘That darn wabbit!’

Bugs Bunny, first seen in Porky’s Hare Hunt (1938), had a complicated cross-bred genealogy. Remembering the ‘What’s up, Doc?’ expression from his high-school days in Texas, Avery had decided to place it in the mouth of a sharp Brooklynese rabbit who knew everything. Avery later recalled in an interview:

‘So when we hit on the rabbit we decided he was going to be a smart-aleck rabbit, but casual about it, and I think the opening line in the first one was, “Eh, what’s up, Doc?,’ And gee, it floored ’em! Read more

From the November 1, 1995 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Simultaneously quite watchable and passionless, Martin Scorsese’s three-hour dissection of power in Las Vegas (1995), set principally in the 70s, sometimes comes across like an anthology of his previous collaborations with Robert De Niro — above all GoodFellas, though here the characters are high rollers to begin with. By far the most interesting star performance is by Sharon Stone as a classy hooker destroyed by her marriage to a bookie (De Niro, in the least interesting star performance) selected by the midwest mob to run four casinos. There’s an interesting expositional side to the film, with De Niro and Joe Pesci’s characters both serving as interactive narrators, but the film never becomes very involving as drama, and the appropriation of Georges Delerue’s theme from Godard’s Contempt is the tackiest hommage since the use of Singin’ in the Rain in A Clockwork Orange. With James Woods, Don Rickles, Alan King, Kevin Pollak, and L.Q. Jones. (JR)

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 3, 2008). This was the last of my annual “ten best” pieces for the Reader. — J.R.

If I were playing by the usual rules, the contenders for my best of 2007 list would be drawn from the titles only millionaires could afford to promote. In that case, I would say 2007 was the worst year for new movies I could remember. But I’d be fudging, because I didn’t come close to seeing all the contenders.

Who did? Film Comment recently put together a list of eligible titles for its own annual poll. It’s 105 pages long, with roughly 23 films per page — more than 2,400 titles. “Major studios” released 119 films, or about one-twentieth of the total (I saw 33 of them), and 49 more came from “specialty divisions” (I saw 22 of those). “Independent distributors” were behind nearly 500 (90 of which I saw). The remaining 1,600-plus titles came out of festivals (where I saw about 50 not included in the other lists).

At least 30 of the movies I saw were so forgettable that I had to look them up in the Reader’s movie database to remind myself what they were about. Read more

From Sight and Sound (Autumn 1974). — J.R.

The first and perhaps the final question to be asked about Peter Bogdanovich’s adaptation of Henry James’ novella is simply why he chose to embark on it. A revealing interview with the director by Jan Dawson which appeared in Sight and Sound last winter affirms that he is anything but a Jamesophile (‘The social aspects of it don’t really concern me’), and one would imagine that taking up an admittedly minor — if commercially celebrated — work by the grey eminence would at least be dictated by an interest in the tale as ‘raw material’, an expedient for arriving at his own creation. But the confounding thing about his Daisy Miller is that it comes across as neither fish nor fowl: too indifferent to Jamesian nuance to qualify as appreciation, too faithful (in terms of the overall plotting and dialogue in Frederic Raphael ‘s script) to gain credence as an attack on the original — and yet too amorphous and uncertain in its own terms to register as an independent and autonomous work.

One suspects that the attractions of the project were the mythic elements: American innocence and charm in confrontation with European decadence. Read more

The following was commissioned in 1999 by Written By, the magazine of the Writers Guild, which decided not to run it because Brooks’s agent refused to let me see The Muse in advance for this article unless a “cover story” was promised. Written By, to its credit, refuses to make deals of this kind. So the magazine paid me for the article and didn’t run it, which I hope made Brooks’s agent properly proud of his efforts. — J.R.

You may recall him as the wealthy convict in Out of Sight, or, prior to that, as Cybill Shepherd’s wisecracking cohort at the campaign headquarters in Taxi Driver, as Holly Hunter’s best friend in Broadcast News, or as the neurotic Hollywood producer in I’ll Do Anything. Maybe, if you’re luckier, you’ve seen his five underrated and highly durable comedies — Real Life (1979), Modern Romance (1981), Lost in America (1985), Defending Your Life (1991), and Mother (1996) — which will be succeeded later this year by The Muse.

Albert Brooks has so far taken solo writing credit only on Defending Your Life — sharing script credit with TV comedy writer Monica Johnson on the other four (as well as on The Scout, a disappointing 1994 baseball movie he didn’t direct), and also with Harry Shearer on Real Life, the first and probably the funniest of the lot. Read more

This was written for the Writers Guild magazine Written By; it ran in their August 1997 issue and was later reprinted in my collection Essential Cinema.

My comparison of May with Erich von Stroheim, which may sound frivolous, is actually something I take very seriously. Both filmmakers are mainstream figures with the temperaments of avant-garde artists; Orson Welles’ description of Stroheim’s style as “Jewish baroque” also fits May’s quite well; and perhaps most significantly of all, both of these highly obsessional writer-director-performers create films populated almost exclusively by monsters, yet characters whom their creators clearly love. In this latter respect, May might even be considered more radical than Stroheim because one can’t cite a single villain in her four features — unlike, say, Schani the butcher (Matthew Betz) in Stroheim’s The Wedding March. Furthermore, for me, the two greatest Stroheim films, Foolish Wives and Greed, are echoed in many respects by The Heartbreak Kid and Mikey and Nicky, the two best films of May.

On the evening of June 27, 2010, in Bologna, Italy, I had the rare, unexpected, and delightful privilege of spending a couple of hours with May. It was a friendly conversation over dinner rather than any sort of interview, but she did tell me in passing a few things about her life and work that I’ve added to this piece as footnotes. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 4, 2007). — J.R.

I’d like to think Elaine May had it written into her contract that the Farrelly brothers could remake her most brilliant comedy (1972) only if they left her name out of the press materials. She’s lucky to go uncredited (Neil Simon, who wrote the original script, is less fortunate), because you can’t do character-driven comedy without characters, and this one has only grotesques who change traits from moment to moment. Given the joyless vulgarity and absence of laughs, the frenzied changes in locales and character types hardly matter. A guy who sells sporting goods (Ben Stiller) gets married, drives south with his bride (Malin Akerman) on their honeymoon, and promptly falls in love with another woman (Michelle Monaghan) while discovering he hates his wife, but the ethnic humor that gave May’s movie its charge is replaced by crass mean-spiritedness. If I were in movie hell, I’d rather see Good Luck Chuck again than return to this atrocity. R, 115 min. (JR)

Read more