From Sight and Sound (Autumn 1974). — J.R.

The first and perhaps the final question to be asked about Peter Bogdanovich’s adaptation of Henry James’ novella is simply why he chose to embark on it. A revealing interview with the director by Jan Dawson which appeared in Sight and Sound last winter affirms that he is anything but a Jamesophile (‘The social aspects of it don’t really concern me’), and one would imagine that taking up an admittedly minor — if commercially celebrated — work by the grey eminence would at least be dictated by an interest in the tale as ‘raw material’, an expedient for arriving at his own creation. But the confounding thing about his Daisy Miller is that it comes across as neither fish nor fowl: too indifferent to Jamesian nuance to qualify as appreciation, too faithful (in terms of the overall plotting and dialogue in Frederic Raphael ‘s script) to gain credence as an attack on the original — and yet too amorphous and uncertain in its own terms to register as an independent and autonomous work.

One suspects that the attractions of the project were the mythic elements: American innocence and charm in confrontation with European decadence. In James’ terms, the contrast is centrally defined by the viewpoint of Winterbourne, a Europeanized American who, by his own rueful admission, has ‘lived too long in foreign parts’, and who oscillates uneasily between the more snobbish sense of propriety of his aunt Mrs. Costello and the haughty Mrs. Walker (both Americans) and his infatuation with the flirtatious appeal of Daisy, who spends her own time abroad in defiance of the local social mores, before tragically dying of Roman fever incurred by her insistence on visiting the Colosseum by moonlight. The comic paradox of Daisy’s collision with ‘European society’ is that all the central characters are Americans (excepting only the pathetic Giovanelli, an Italian bumpkin whose appearances with Daisy cause most of the scandals); and the tensions mainly seem to derive from their varying degrees of self-consciousness about their European surroundings, with Vevey and Rome serving as the crucial backdrops.

The social customs which Daisy flouts are defined by James’ milieu circa 1878, and the mere reproduction of them in a contemporary work obviously leads to difficulties that must be circumvented either by irony or the precise decision to treat the original as a period piece. Bogdanovich’s approach falls somewhere in between these solutions, treating Winterbourne’s vacillations — and Mrs. Walker’s climactic snubbing of Daisy at a social gathering — as though they were as ambiguous and abnormal as the heroine’s own behavior, and rendering the relationship between Winterbourne and Daisy almost exclusively as a failed love story.

Clearly what the film requires in order to skirt this thin ice is a solid sense of history; what is mainly offered in its place is a sense of movie history, and pretty familiar survey material at that. However much Targets and The Last Picture Show, Bogdanovich’s first two films, may have relied on the work of other directors, one generally felt that these were being used as stylistic guidelines, nor as life preservers. Working for the first time without the talents of PoIly Platt as production designer, in a period and on a continent where he has to depend more on intuition than experience, Bogdanovich appears to have sought the examples of his mentors more strenuously than before.

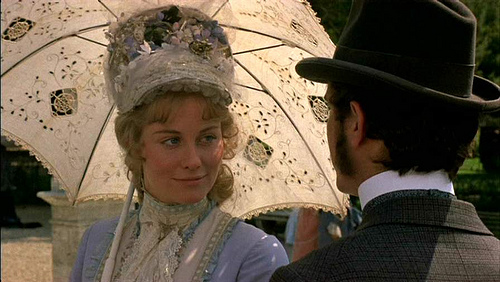

The results are sad indeed: what seems intended as an evocation of The Magnificent Ambersons comes much closer to the disjointedness of The Trial, but without the exuberance or the experimental inventiveness that animated Welles’ own miscalculation. Stationing a plaintive sounding harmonica player in the vicinity of Daisy and Winterbourne’s castle visit at Chillon — and then reprising his tune over the final credits — comes across as a case of misapplied Ford to telegraph a mood of nostalgia. And having Cybill Shepherd as Daisy race through her opening dialogue like some amalgamation of a Hawks heroine and a field-track runner merely bypasses the material instead of confronting it. (Matters are not helped much by Cybill Shepherd’s inflections: persuasive as a Texas tease in The Last Picture Show and more than adequate, under Elaine May’s expert direction, as a Minnesota wish-fulfillment in The Heartbreak Kid, she is scarcely believable at all when she impersonates Daisy in an accent a good thousand miles south of Schenectady.)

Most of the trouble throughout amounts either to reductiveness of this sort or over-calculation. The potentially hilarious lines of Randolph — Daisy’s philistine younger brother whose various outrages are often heightened versions of her own — are usually derailed by the decision to direct him as a conventional Hollywood brat. ‘I never saw anything so pretty,’ Daisy remarks of the Colosseum in the original; substituting ‘quaint’ for ‘pretty’ tends to make her innocence seem more moronic than charming.

Ever an intrinsically good idea, like the last shot — the camera drawing away from Winterbourne (Barry Brown) at Daisy’s funeral while we hear the subsequent dialogue between him and his aunt – is marred by a freeze-frame and a whitening out of the image, simplicity quickly losing out to overkill. Original locations traversed with Lubitsch-like discretion or glimpsed from Wellesian low-angle shots (to suggest fatality) are unfortunately not enough; and as the film progresses one becomes increasingly grateful for the quiet authority of Mildred Natwick’s Mrs. Costello, suggesting more of James’ world in single lines than the remainder of the film in all its exertions.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM