Monthly Archives: March 2022

GHOST STORY (1975 review)

From Monthly Film Bulletin, July 1975 (vol. 42, no. 498). –- J.R.

Ghost Story

Great Britain, 1974

Director: Stephen Weeks

England; 1930. Talbot and Duller, former schoolmates of

McFayden, are summoned by the latter to a country house

supposedly belonging to a friend of his father for a weekend

of grouse hunting. Ragged and isolated by the other two for

his callow enthusiasm, Talbot is puzzled to find a warm

teacup and an odd-looking doll in his bedroom. In the

morning, he witnesses a scene in the parlor enacted by

people living forty years ago: Robert Quickworth signing

his sister Sophy over to Dr. Borden’s insane asylum, despite

the protests of her maid. At first Talbot assumes this to be

an elaborate practical joke, but after seeing people who

resemble these characters in the village pub and

dreaming or half-dreaming further episodes — in which

the doll leads him to Borden’s asylum -– he becomes

increasingly obsessed with the intrigue. Meanwhile

Duller, who has come to the house to seek ghosts with

‘scientific’ equipment, is disgruntled when all his

experiments fail and he insists on leaving. McFayden

confesses to Talbot that he has recently inherited the

house and invited him and Duller there to ‘test’ it

for ghosts, mentioning a cousin of his father’s who

went mad there. Read more

Hot Blood

From the March 15, 2002 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

While not really a success, Nicholas Ray’s 1956 film about urban Gypsies, made between two of his near-masterpieces (Rebel Without a Cause and Bigger Than Life), has its share of interesting moments and vibrant energies, many of them tied to Ray’s abiding interest in the folkloric. In some respects this color ‘Scope feature comes closer than any of his other movies to the musical that Ray always dreamed of making: there’s a defiant dance on the street performed by Cornel Wilde, a dynamic whip dance between Wilde and Jane Russell that’s even more kinetic, and a Gypsy chorus that figures in other parts. Definitely one of the more intriguing and neglected of Ray’s second-degree efforts. 85 min. A 35-millimeter ‘Scope print will be shown. Gene Siskel Film Center, 164 N. State, Sunday, March 17, 6:00, 312-846-2800.

Eleven Treasures of Jazz Performance on DVD

Commissioned and published by DVD Beaver in 2007. In 2015, Ehsan Khoshbakht and I put together a sidebar for Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna, Italy, “Jazz Goes to the Movies,” and then a reconfigured version of this a few months later at the Festival on Wheels in Ankara, Turkey, which led both of us to revisit many of these titles and releases. — J.R.

Broadly speaking, there are two kinds of jazz films — documentary records of particular jazz performances and narrative films that incorporate jazz in some fashion, in their soundtrack scores and/or in their stories. But in some cases, identifying which films belong in which category is simply a matter of personal taste. Consider, for instance, Black and Tan and St. Louis Blues, two landmark jazz shorts directed in 1929 by Dudley Murphy —- a fascinating figure who straddled the avant-garde and the mainstream, having both collaborated with Fernand Léger on Ballet mécanique and Paul Robeson on The Emperor Jones and directed several Hollywood pictures, and who’s been receiving some belated recognition lately thanks to Susan B. Delson’s excellent biography, Dudley Murphy: Hollywood’s Wild Card (University of Minnesota Press, 2006). I would argue that Black and Tan, which stars Duke Ellington, is important chiefly as a narrative film, whereas St. Read more

Home movie of homelessness (Review of REMINISCENCES OF A JOURNEY TO LITHUANIA)

One of my first published reviews, which appeared in the November 2, 1972 issue of The Village Voice, this was commissioned by Andrew Sarris, bless him. I was always grateful for this opportunity to write about a film that I love, and that I continue to cherish. — J.R.

Jonas Mekas’s Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania, a film dedicated “to all the displaced people in the world,” has itself become the object of some displacement. Screened jointly with Adolfas Mekas and Pola Chapelle’s Going Home at the New York Film Festival, defined in the program as a non-narrative film and by its author as a home movie, it has become a casual victim of “convenient” programing and somewhat deceptive labels. Whatever “non-narrative” and “home movie” mean — and I think the latter describes Going Home pretty accurately — they are less than helpful in describing the achievement of what must be called Jonas Mekas’s testament. If they must be understood, let it be understood that Reminiscences is a home movie about homelessness, a non-narrative film with one of the most beautifully constructed and articulated narrative lines in autobiographical cinema.

Going Home, a rambling collection of travel photos and family poses, resembles the jazzy surfaces of Hallelujah the Hills, joke titles and all, and registers not unlike a boastful list of possessions (the secret metaphysic behind every family album): this is my garden, my Moscow, my family, my Lithuania. Read more

CHUNHYANG: Im Kwon-taek’s Shotgun Marriage

Written for the Busan International Film Festival’s Korean Film retrospective catalogue, Fly High, Run Far: The Making of Korean Master IM Kwon-taek, Fall 2013. — J.R.

Preface

I can’t pretend to be familiar with Korean history in general and traditional Korean music in particular. But rather than attempt to disguise my ignorance with a handful of facts gleaned from superficial research, I prefer to approach Chunhyang (2000, 136 min.) in broader, more generalized, and less historical terms as a film confronting issues of representation relating to live performance as well as cinema, and the survival of relatively ancient forms of music and performance in the present.These are the issues that have drawn me to Chunhyang in the first place, despite an overall ignorance about Korean culture that extends to most of its cinema — including even most of the oeuvre of its most celebrated auteur, Im Kwon-taek.

I hope that this admission of my lack of knowledge and innocence can be regarded as a form of clarification and honesty rather than as an expression of arrogance. My theoretical assumption is that the most common form of journalistic bluff regarding such matters — conveying an unearned and unwarranted stance of authority, typically justified through a series of lazy intellectual shortcuts and/or appropriations (such as, for example, describing pansori as some Korean variant of the American blues) — is ultimately more imperialistic in effect than any honest admission of cultural ignorance. Read more

My Dozen Favorite Non-Region-1 Box Sets

From DVD Beaver (posted June 2008). Some of these listings may be out of date — and in the case of Godard’s Histoire(s), superseded by subsequent American and/or Blu-Ray editions. — J.R.

Coming up with my favorite box sets from abroad is a far cry from compiling a list of my favorite films on DVD, foreign or otherwise, even if some of my favorite films are represented here. The problem is, as Mick Jagger puts it, you can’t always get what you want. To start with an extreme example, my favorite Hou Hsiao-hsien film is most likely The Puppetmaster (1993), but my least favorite of all the DVDs of Hou films in my collection happens to be the Winstar edition of that film. It’s so substandard —- not even letterboxed, and packaged so clumsily — that I’m embarrassed to find myself quoted on the back of the box, especially with the quotation mangled into tortured grammar.

I’ve aimed for a certain geographical spread as well as some generic balance: popular comedies, art films, experimental films, and one serial; DVDs from Belgium, France, Hong Kong, Italy, Japan, and the United Kingdom. Admittedly, roughly half of my selections come from France, and a quarter of them, to my surprise, comes from a single label, Gaumont —- maybe because this blockbuster company seems to specialize in blockbuster box sets. Read more

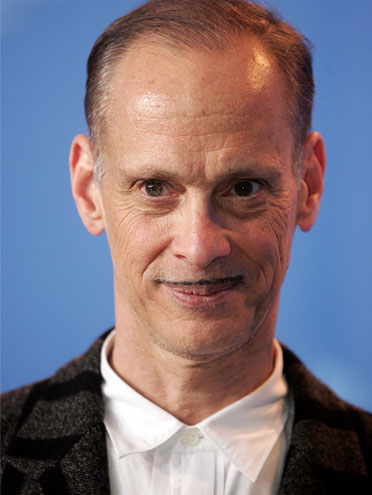

Excremental Visionary (on John Waters’ SHOCK VALUE)

From The Soho News (September 22, 1981). — J.R.

Shock Value: A Tasteful Book about Bad Taste By John Waters Delta, $9.95

If conventional means wedded to conventions, then John Waters, amiable sleaze director of Pink Flamingos, Female Trouble, and Polyester. is as conventional as you or I, maybe even more so. The not-so-surprising thing about Shock Value, a “tasteful” (meaning cautious) memoir about his special brand of bad taste, is that it proves him to be literary, too — at least in a minor Mark Twain vein. Pithy aphorisms rub shoulders with sly asides and wry homilies. Here are a few jewels among gritty jewels:

All people look better under arrest.

***

I never watch television because it’s an ugly piece of furniture, gives off a hideous light, and, besides, I’m against free entertainment.

***

Since the character [in Female Trouble] turns from teenage delinquent to mugger, prostitute, unwed mother, child abuser, fashion model, nightclub entertainer, murderess, and jailbird, I felt at last Divine had a role she could sink her teeth into.

***

Sometimes I just sit on the street and wait for something awful to happen.

***

The more obscure a town I visit, the greater appeal it has for me, since I figure there’s an audience for anything in New York, but if you can get a following in, say, Mobile, Alabama, you really must be doing something right. Read more

Ten Overlooked Fantasy Films on DVD (and 2 more that should be)

Posted by DVD Beaver in October 2007; I’ve updated many of the links. — J.R.

As with science fiction, the focus of my previous article in this series, the definition of what constitutes a fantasy film is to some extent arbitrary. Not every account of The Tiger of Eschnapur would situate it within the realm of fantasy, though I’d argue that a sequence involving a spider’s web that’s woven in the entrance to a cave, and perhaps other details as well, warrant such a description. The some goes for Confessions of an Opium Eater and its sudden shifts into slow-motion; these are nominally justified as opium-induced perceptions, but when the hero suddenly falls from a building and does several rapid cartwheels in midair, it’s impossible to tell at which point the logic of dreams takes over. In other respects, accepting Eyes Wide Shut as a fantasy is more a matter of interpretation than a matter of pointing at any obvious genre elements. And of course the realm of horror, which overlaps with fantasy without necessarily becoming fantasy (as in the cases of The Seventh Victim, Psycho, and Peeping Tom, for instance), accounts for at least four of my selections—Vampyr, Night of the Demon, The Masque of the Red Death, and Martin. Read more

Mise en Scène as Miracle in Dreyer’s ORDET

Like my essay on Dreyer’s Day of Wrath, this essay was written for an Australian DVD, which came out in 2008 on the Madman label. (One can order these and many other DVDs, incidentally, from Madman’s site.) My thanks to Alexander Strang for giving me permission to reprint this. (It’s also reprinted in my most recent collection, Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia. —J.R.

Mise en Scène as Miracle in Dreyer’s Ordet

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Ordet (The Word, 1955) was the first film by Carl Dreyer I ever saw. And the first time I saw it, at age 18, it infuriated me, possibly more than any other film has, before or since. Be forewarned that spoilers are forthcoming if you want to know why.

The setting and circumstances were unusual. I saw a 16-millimeter print at a radical, integrated, co-ed camp for activists in Monteagle, Tennessee — partially staffed by Freedom Riders, during the late summer of 1961, when we were all singing “We Shall Overcome” repeatedly every day. So the fact that Ordet has a lot to do with what looked like a primitive form of Christianity — combined with the particular inflections brought by the black church to the Civil Rights Movement, including one of its appropriated hymns — had a great deal to do with my rage. Read more

Fresh Clues to an Old Mystery [THE BIG SLEEP]

From the Chicago Reader, June 20, 1997. — J.R.

The Big Sleep

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Howard Hawks

Written by William Faulkner, Leigh Brackett, and Jules Furthman

With Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, John Ridgely, Martha Vickers, Dorothy Malone, Pat Clark, Regis Toomey, Charles Waldron, Sonia Darrin, and Elisha Cook Jr.

For all its reputation as a classic, and despite the greatness of Howard Hawks as a filmmaker, The Big Sleep has never quite belonged in the front rank of his work — at least not to the same degree as Scarface, Twentieth Century, Only Angels Have Wings, To Have and Have Not, Red River, The Big Sky, Monkey Business, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, and Rio Bravo, to cite my own list of favorites. Unlike To Have and Have Not (1944) — Hawks’s previous collaboration with Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, writers Jules Furthman and William Faulkner, cinematographer Sid Hickox, and composer Max Steiner — it qualifies as neither a personal manifesto on social and sexual behavior nor an abstract meditation on jivey style and braggadocio set within a confined space, though it periodically reminds one that exercises of this kind are what Hawks did best. Read more

Demonlover

This is radically different from Olivier Assayas’s two previous features (Late August, Early September and Les destinees), but it suggests a continuation of his Irma Vep (1996) in its narrative ambiguity and its feeling for contemporary conspiracy. The main difference is that Assayas seems more deliberate now in tapping his unconscious, making the aura of mystery somewhat more willful. This begins as a sleek paranoid thriller about a multinational conglomerate, dominated by women (Connie Nielsen, Chloe Sevigny, Gina Gershon), that traffics in 3-D manga porn, and though the backdrop shifts from Tokyo to Paris to rural Texas, the film ultimately slides into a netherworld where it’s impossible to distinguish fact from fantasy. It’s gripping and provocative, making effective use of actor Charles Berling and the music of Sonic Youth, though I wish it were a little less indebted to David Cronenberg’s Videodrome. In English and subtitled French. 128 min. Landmark’s Century Centre.

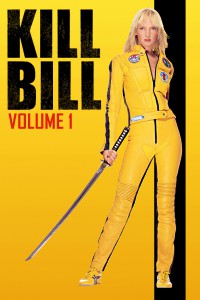

Kill Bill Vol. 1

From the Chicago Reader (October 10, 2003). — J.R.

Quentin Tarantino’s lively and show-offy 2003 tribute to the Asian martial-arts flicks, bloody anime, and spaghetti westerns he soaked up as a teenager is even more gory and adolescent than its models, which explains both the fun and the unpleasantness of this globe-trotting romp. It’s split into two parts, and I assume the idea of volumes reflects the mind-set of a former video-store clerk who thinks in terms of shelf life. This is essentially 111 minutes of mayhem, with hyperbolic revenge plots and phallic Amazonian women behaving like nine-year-old boys; the dialogue, less spiky than usual, uses bitch as often as his earlier films used nigger, and most of the stereotypes are now Asian rather than black. If Jim Jarmusch’s Ghost Dog was a response of sorts to Tarantino, then Tarantino returns the compliment here with RZA’s music and the mixture of Japanese and Italian genre elements. With Uma Thurman, Lucy Liu, Sonny Chiba, Daryl Hannah, Julie Dreyfuss, and Chiaki Kuriyama. R. (JR)

Power Surge

Chicago International Film Festival coverage, from the Chicago Reader (October 10, 2003). — J.R.

Among the films screened at the Toronto film festival last month that will turn up here eventually was Jim Jarmusch’s Coffee & Cigarettes, which taught me something about the complex ethics of celebrity — including the resentment fame can foster in noncelebrities and the defensiveness this resentment can provoke in turn. It also showed me how a cycle of comic black-and-white shorts can become a thematically and formally coherent feature. Other festival films were equally edifying, in their own ways. Ann Marie Fleming’s The Magical Life of Long Tack Sam — a playful, speculative documentary about Fleming’s once-famous great-grandfather, a Chinese stage magician who toured around the world — tells the story of his life by telling the history of the 20th century.

In The Saddest Music in the World Guy Maddin applies his hallucinatory, pretalkie visual style to a characteristically deranged script, which has hilarious things to say about how the colonialist chutzpah of big business in the U.S. looks to a cowering Canadian artist. Errol Morris’s documentary about Robert McNamara, The Fog of War, suggests, among other things, that in terms of power relations Morris is ultimately as subservient to McNamara as McNamara once was to Lyndon Johnson. Read more

See the World

From the Chicago Reader (October 3, 2003). — J.R.

A friend of a friend recently visited an uncle who’d just come back from fighting in Iraq. He conceded that the invasion hadn’t reduced the threat of terrorism or uncovered any weapons of mass destruction or exposed any links between September 11 and Saddam Hussein. “Just the same,” he said, “September 11 happened almost two years ago — and somebody’s got to pay.”

I was reminded of his words a couple days later at the Toronto film festival, when I saw Gus Van Sant’s Elephant — a fiction film about the 1999 killings at Columbine High School. No one has been able to adequately explain that massacre, and Van Sant doesn’t even try. Yet one of the teenagers’ motives may well have been “somebody’s got to pay.”

Elephant is Van Sant’s first decent film in years, but it made Variety‘s Todd McCarthy so indignant when it premiered at Cannes this past spring that his anger may have been the biggest news at that festival. This is less peculiar than it sounds, since the Cannes festival is held mainly for the press — unlike the Chicago festival, which is held for the public, or the Toronto festival, which is held for the press, the industry, and the public — and that creates an overheated critical climate where all the competing films are commonly declared either wonderful or terrible. Read more