From The Soho News (September 22, 1981). — J.R.

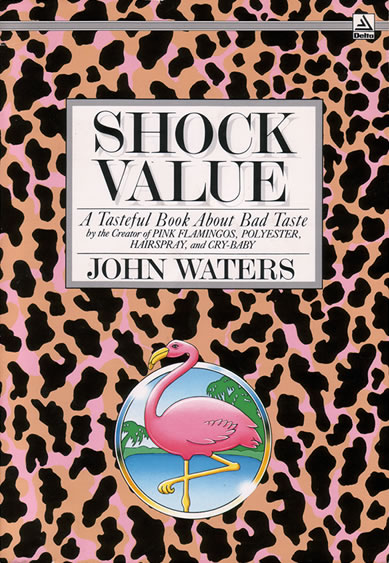

Shock Value: A Tasteful Book about Bad Taste By John Waters Delta, $9.95

If conventional means wedded to conventions, then John Waters, amiable sleaze director of Pink Flamingos, Female Trouble, and Polyester. is as conventional as you or I, maybe even more so. The not-so-surprising thing about Shock Value, a “tasteful” (meaning cautious) memoir about his special brand of bad taste, is that it proves him to be literary, too — at least in a minor Mark Twain vein. Pithy aphorisms rub shoulders with sly asides and wry homilies. Here are a few jewels among gritty jewels:

All people look better under arrest.

***

I never watch television because it’s an ugly piece of furniture, gives off a hideous light, and, besides, I’m against free entertainment.

***

Since the character [in Female Trouble] turns from teenage delinquent to mugger, prostitute, unwed mother, child abuser, fashion model, nightclub entertainer, murderess, and jailbird, I felt at last Divine had a role she could sink her teeth into.

***

Sometimes I just sit on the street and wait for something awful to happen.

***

The more obscure a town I visit, the greater appeal it has for me, since I figure there’s an audience for anything in New York, but if you can get a following in, say, Mobile, Alabama, you really must be doing something right.

***

Since [the Hanafi Muslim sect] had given the ultimate bad movie reviews by killing people to protest the showing of Mohammad, Messenger of God, one could only tremble at the thought of what they might have pulled had they seen, say, The Deep.

***

I think it’s healthy to see your parents often (sort of a tune-up), but I think it’s neurotic to actually hang around with them.

A Grove Press freak around the same time that he was getting expelled from NYU for a pot bust, Waters has a flaky imagination that is often furnished by the conceits of Genet and Burroughs. The former is undoubtedly responsible for both the moniker of Divine (his principal star, a larger-than-life drag queen — described as a she or he according to context) and the equally passionate “crime is beauty” poetics of Waters’ masterpiece and concerto for Divine, Female Trouble. It was Genet, after all, who once defined art as the capacity to make you eat shit and like it — which is just what Divine visibly does with dog crap in the celebrated and climactic showstopper of Pink Flamingos. William S. Burroughs, on the other hand, who offers a blurb on the back of Shock Value, can easily be detected in a passage like the following, which describes a Baltimore dusk-to-dawn kung-fu grindhouse so scuzzy and violent that even Waters stays away: I’ve always imagined huge crowds inside, some shooting up, others guzzling from brown paper bags. Hopped-up ushers patrol with nightsticks instead of flashlights and break up popcorn-snatchings, switchblade fights, and gang bangs. The audience pelts the screen with leftovers from the day’s robberies and breaks into karate fights whenever Bruce Lee appears on the screen. Driven to hysteria by all the gore, they take audience participation to new heights by stabbing and shooting one another, all in the name of entertainment.

Unlike Genet or Burroughs,Waters can’t really be considered a tough customer. There is nothing at all in Shock Value about his sex life and sexual preferences, for instance, or the charming ten-minute exploitation spin-off he shot in 1970 called The Diane Linklater Story. But you can learn all you want to about how the uglier shock effects in his low-budget movies are achieved. As it happens, the shit-eating in Pink Flamingos is real, while the shit-stain on Divine’s underpants when (through the miracle of the medium) he fucks himself in Female Trouble is fake. Yet one suspects that if the reverse were true, no essential facet of Waters’ aesthetics would be violated. Regarding vomit, he freely admits that after prolonged efforts to get Divine to barf for real in his movies, he finally had to simulate the desired act with a can of creamed corn, some catsup, and a little water. (Can we possibly find it in our hearts to forgive him?) After commenting rather eruditely on the importance of vomit in Swedish films of the 60s, he roundly condemns “films such as An Unmarried Woman for including vomit scenes that are patently unauthentic.”

***

Despite these and other fixations, it’s pretty evident throughout that Waters cares more about people than he does about either puke or pimples. And, grotesque as it may seem, the other film director’s autobiography that Shock Value most reminds me of is Jean Renoir’s My Life and My Films — in part because of its rich and diverse enjoyment of human nature. Renoir often appreciates friends for their animal natures; Waters is thrilled by a mean, toothless hillbilly woman glaring at Perrier bottles in a supermarket, “unable to contain her rage that somebody was stupid enough to buy water.” “Look at those disgusting trees stealing my oxygen!” shreiks Mink Stole as she speeds down the highway in Desperate Living — the only major Waters movie without Divine, hence missing what F.R. Leavis would call a moral center. But look at all the other Waters regulars congregating around the edges — from the hideously made-up Susan Lowe (whose physical transformation is illustrated here in photos) to the batty and babbly Edith Massey to the 400-pound Jean Hill — and they embody a moral universe of some ferocity, one that Waters ultimately backs to the hilt.

A line from the synopsis of Female Trouble oddly evokes the tortured world of A Confederacy of Dunces: “Taffy grows into a severely maladjusted young lady, tracks down her father and kills him, and in one final act of rebellion turns Hare Krishna to get on her mother’s nerves.” Perhaps more significant is the fact that for Waters, “the most chic and glamorous” opening of the film was in the Baltimore City Hall Jail, which had previously allowed him to shoot on the premises, and that the response of the prisoners to the movie “would mean a lot more to me than the New York Times review.” “Multiple Maniacs really helped me to flush Catholicism out of my system, but I don’t think you ever can lose it completely,” begins one paragraph, which ends, “Being Catholic always makes you more theatrical.” In a way, Waters seems about as socially well-adjusted as Salvador Dali and the late Flannery O’Connor, two other excremental Catholic visionaries and gifted, gabby self-publicists with a taste for violent splash. He almost gives the whole game away when he describes shooting a scene in Female Trouble in which Divine, Cookie Mueller, and Susan Walsh cut their fingers with a razor to pledge their “sisterhood”. One of the actresses, he reports, got too carried away, cut too deeply, and passed out as soon as the take was over; but this scene was cut out of the final film because the shadow of the mike was visible. In other words, blood runs deep, but illusionism in a Waters movie runs still deeper. He’s still assuring readers in the last paragraph of the book that he only thinks terrible thoughts, he doesn’t live them — an American transcendentalist through and through.

In spite of the author’s cheerful morbidity about following and aesthetically relishing trials and violent crimes (he boasts ordering tapes of the mass suicides in Guyana through a New York Times ad, and playing them at his parties when he wants his guests to leave), he turns out to be an old-fashioned humanist, too. Significantly, in my favorite chapter, “Baltimore, Maryland — Hairdo Capital of the World,” which clarifies his vision of the world as much as anything does, he allots roughly equal space to Mrs. Mac, the Rat Lady — a black woman who goes out every day in her Ratmobile to hunt down and exterminate slum rodents — and William Donald Schaeffer, the mayor, both of whom he clearly reveres. He’s never more American — at least in the home-grown, naïve sense — than when he claims to be apolitical. At the Berlin Film Festival, he tells us, the “buffs are unbelievably serious and went crazy when I told them my films aren’t political. ‘Yes they ARE!!’ they screamed, and I backed off a little; I guess you can read anything you want into a screenplay.” Nonsense. The anarchist delirium of Pink Flamingos and Female Trouble — more relevant to life, I would think, than to art — is as wide as Waters’ aesthetic range as a filmmaker is narrow. As a writer, though, he belongs strictly to the mainstream. The truth of the matter is that Waters is a fellow who picks up the same sort of maladjusted strays that a Reaganite would quickly consign to the incinerator — a moralist with some wit who not only protects and nurtures these strays but also organizes them (see Desperate Living), respects them, and trains them, allows them to grow teeth, and enables them to fight back. John Waters not political? Give me a break.

— The Soho News, September 22, 1981