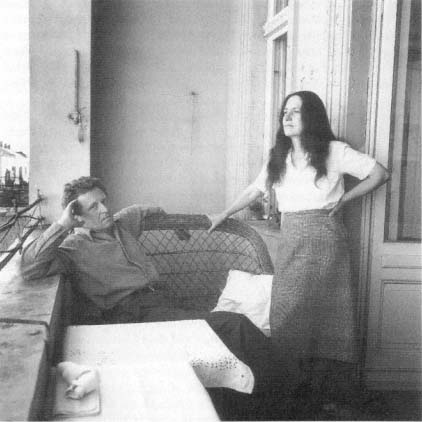

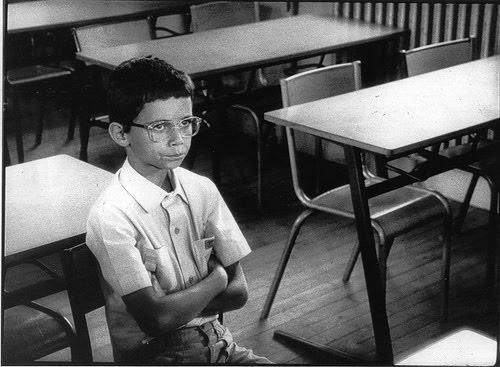

Prior to the more recently held retrospectives in the U.S. devoted to Jean-Marie Straub and the late Danièle Huillet, the only previous such retrospective was held on November 2-14, 1982, at New York’s Public Theater. I curated this event, which also included a selection of films by others made by Jean-Marie and Danièle to show with their own. For the occasion, I also edited a 20-page, tabloid-sized catalogue, long out of print, and what follows are (1) the full program as planned and (2) my introduction. Regarding (1), I recall now that there was one last-minute addition, their recently completed short film En rachâchant (see second photograph below), as well as some last-minute omissions or substitutions that are noted in the text below. Regarding (2), I should emphasize that a lot has changed and developed over the past three decades, both in myself and in Straub-Huillet’s work –- in both cases, I’d like to think, for the better. It’s cheering to note that no less than three very substantial books have appeared devoted to their work, two in English — their Writings (as translated and edited by Sally Shafto, published in New York by Sequence Press), and an excellent critical collection edited by Ted Fendt for the Austrian Filmmuseum — and a mammoth collection in French, Internationale Straubienne, published jointly by Editions de l’Oeil and the Centre Pompidou (to accompany their own retrospective). — J.R.

The Cinema of Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet

November 2-14, 1982

Nov. 2: MACHORKA-MUFF (1963)

NICHT VERSÖHNT (NOT RECONCILED, 1965)

plus ANTONIO DAS MORTES (Glauber Rocha, 1969)

Nov. 3: CHRONIK DER ANNA MAGDALENA BACH

(CHRONICLE OF ANNA MAGDALENA BACH, 1968)

EINLEITUNG ZU ARNOLD SCHÖNBERGS BEGLEITMUSIK ZU EINER LICHTSPIELSZENE (INTRODUCTION TO ARNOLD SCHÖNBERG’S “ACCOMPANIMENT TO A CINEMATOGRAPHIC SCENE,”‘ 1972)

plus VREDENS DAG (DAY OF WRATH, Carl Dreyer, 1943)

Nov. 4: OTHON (1969)

”TOUTE REVOLUTION EST UN COUP DE DÉS” (EVERY REVOLUTION IS A THROW OF THE DICE, 1977)

plus A KING IN NEW YORK (Charles Chaplin, 1957)

Nov. 5: GESCHICHTSUNTERRICHT (HISTORY LESSONS, 1972)

DER BRAUTIGAM, DIE KOMODIANTIN UND DER ZÜHALTER (THE BRIDEGROOM, THE COMEDIENNE, AND THE PIMP, 1968)

plus A CORNER lN WHEAT (D.W. Griffith, 1909)

LAS HURDES (LAND WITHOUT BREAD, Luis Buñuel, 1932)

CIVIL WAR (John Ford, 1962)

Nov. 6 & 7: MOSES UND ARON (MOSES AND AARON, 1975)

plus ALEXANDER NEVSKY (Sergei Eisenstein, 1938) (matinees)

BLIND HUSBANDS (Erich von Stroheim, 1918) (evenings)

Nov. 9: FORTINI-CANI (I CANI DEL SINAI/THE DOGS OF SINAI, 1976)

plus THIS LAND IS MINE (Jean Renoir,1943)

Nov. 10: DALLA NUBE RESISTENZA (FROM THE CLOUD TO THE RESISTANCE, 1978)

TROP TÔT, TROP TARD (TOO EARLY, TOO LATE, 1981)

Nov. 11: FORTINI-CANI

FROM THE CLOUD TO THE RESISTANCE

Nov. 12:FORTINI-CANI

TOO EARLY, TOO LATE

Nov. 13 & 14: FROM THE CLOUD TO THE RESISTANCE

ZANGIKU MONOGATARI (THE STORY OF THE LAST

CHRYSANTHEMUMS, Kenji Mizoguchi, 1939)

UNE AVENTURE DE BILLY LE KID (A GIRL IS A GUN) (Luc Moullet, 1970)

***

Introduction: Once it was Fire

D.W. Griffith at the end of his life: “What modern movies lack is the wind in the trees.”

Rosa Luxembourg: ‘The fate of insects is not less important than the revolution.”

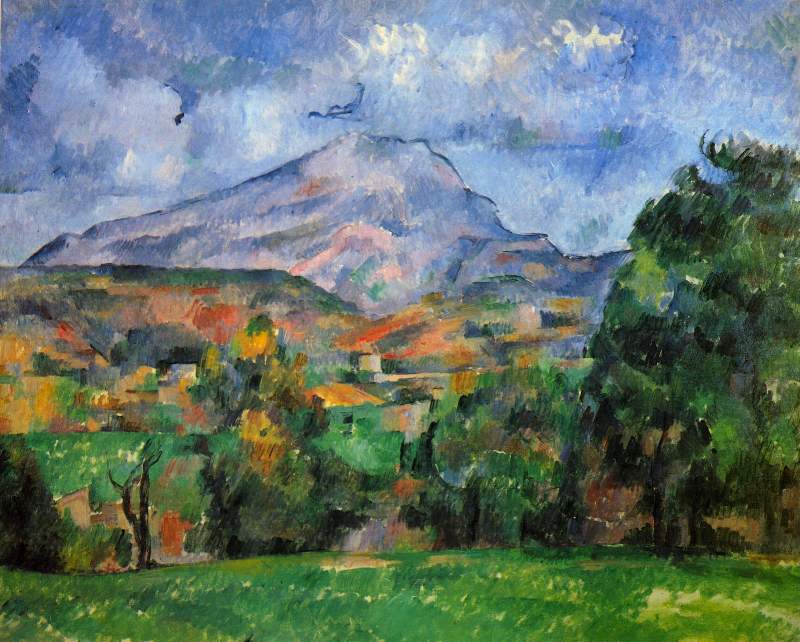

Cézanne, who painted Mont St.-Victoire again and again: “Look at this mountain, once it was fire.”

(Quotations cited by Jean-Marie Straub before screening of Too Early, Too Late at the Collective for Living Cinema in New York City,April 30, 1982)

***

Although this booklet exists chiefly in order to assist the films of Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet -– more precisely, to assist, accompany, and amplify a season consisting of all theirfilms to date and a selection of films by others thatthey consider exemplary to their own practice — it also aims deliberately at being obstinate, angry and difficult in certain ways: unreconciled. For starters, it won’t do to try to convince people that Straub-Huillet films can be as easy to take as gumdrops. One has to acknowledge the problematic side of their work and then do something about it — curse, rage, marvel, give up, renegotiate, avoid, confront.

It’s been said that Straub and Huillet sit around in Parisian cafes trying to dream up ways of forcing audiences to flee from theaters. Actually, such a statement bears some relationship to the truth. Asked at the Edinburgh Film Festival why the log sequences inside a car being driven through Rome in History Lessons were included, Straub replied (I quote from memory), in order to empty the theater, because people who are not able to look at the street will never be able to understand class struggle. (He added that being able to look at the street was not necessarily easy, that it had taken him some time to learn himself .)

This might be regarded dismissively as intransigence pure and simple, like many of Straub and Huillet’s provocative statements. But further reflection may suggest that it is the commercial cinema and its own way of observing and perceiving –- a process that precisely prevents us from looking at the street in any way except falsely, in search of certain things that block our awareness of other things — that is intransigent, perverse and oppressive, and all the more so for being so easy to consume. (“Ninety percent of films are based on contempt for the people who go to see them,” Straub has said.)

***

Undeniably the most European figures in that branch of the neo-Marxist avant-garde that was educated at the Paris Cinémathèque — a group that also includes Godard, Rivette and Moullet — Straub-Huillet are the least chewable, the angriest (“Look at this mountain, once it was fire’’), the most mulish and intractable, and in some respects the most purely beautiful and political in their sounds and images. (What’s most European about them is their assumption that formal beauty and moralityare intimately related; for most American neo-Marxists, they’re entirely different ballgames.) Nothing stylish (Godard), existential (Rivette) or comic (Moullet) ever seems to threaten their iron determination to change the world every time they position a camera and microphone.

Straub-Huillet literally “have no place” in the impoverished consumer and service oriented American film culture that currently dominates the scene; scarcely any place, even, in the timid pages of supposedly enlightened avant-garde magazines like Millennium Film Journal or Film Culture or October (1), which tend to thrive on local talent, unthreatening iconoclasts, and relative conservatives like Frampton or Fassbinder. No film by Straub-Huillet has opened commercially in the U.S. or even played at the New York Film Festival since 1975. (A curious anomaly, since the first eight of their films up through Moses and Aaron — reviewed by Richard Eder in the New York Times as Aaron and Moses — have shown there.)

The various academic and/or marketing categories designed for classifying, grouping, cataloging, studying and consuming films are confounded by the troublesome, cumbersome, ambiguous relations of Straub-Huillet’s films to nationality, genre and authorship. Their conflation and/or confusion of aesthetics with politics and vice versa place too many critics on the spot, forcing certain contradictions to the surface which otherwise might remain peacefully dormant in the theories (acknowledged or otherwise) as well as the practices of such critics. A Kael, Sarris or Denby could not even begin to cope with any of these films on their own terms without cracking apart at the seams — which is already a promising sign. The power and beauty in these films are not the kind that they (or we) can comfortably live with, because they essentially tell us to change our life -– which “movies” aren’t supposed to do, except metaphorically. The trouble with Straub-Huillet: they mean business.

***

A strange two-headed beast, this Straub-Huillet. Notwithstanding all the familiar sexist arguments that reduce this couple to a husband and an assistant, the degree to which every aspect of their work is predicated on a division and sharing of duties cannot be simply rationalized into a solitary genius figure. (This is a problem encountered even by Tony Rayns here, in his otherwise excellent review of Every Revolution is a Throw of the Dice.) Consider, for instance, the degree to which Huillet handles all the business -– a factor in production no less essential than many other aspects.

So what does one call them, how does one write about them, what does one do with them? Like Laura (Riding) Jackson, they tend to confound indexes and standard package labels, not to mention reviews, book spines and marquees. The format of The New Yorker’s very metaphysical, nonmaterialist “Goings on About Town” is not likely to have a good time with them.

On the other hand, certain publications (such as Cahiers du Cinema, Filmkritik, Screen, Wedge and this booklet) tend to coddle and protect Straub-Huillet, reinforcing the same ghetto strategy from within. The most familiar act of piety towards them, by now something of an international mania, is to print one of their scripts — which practically everyone does, and practically no else reads. Certainly these can be useful as work tools -– although the original texts used in each film almost invariably turn out to be more relevant and interesting. (2) The point to be made here is that (a) the printing of these scripts has frequently come to replace the necessary critical work, and (b) the fact that their films are so difficult to grapple with critically is partially what makes them so exciting; they really are doing something new. It should also be noted that some criticism of distinction about their work is already available in English — I’m thinking principally of the four essays in Martin Walsh’s The Brechtian Aspect of Radical Cinema and Jean-André Fieschi’s lyrical outburst in Richard Roud’s Cinema: A Critical Dictionary.

***

It may be possible to argue that anger assumes much the same role in Straub-Huillet’s work that carnality-spirituality assumes in Dreyer’s and Bresson’s. For them, it sometimes Seems that anger and resistance can even become a form of mysticism — or, at the very least, a discipline that constitutes a sheer act of faith. They believe in the world, one is tempted to say; which isn’t true of most of us. (See Straub’s comments, both at the beginning of this lntroduction and in section #3 of “Straub and Huillet on Filmmakers They Like. . .”, about the wind and Griffith. Look at this mountain of cinema, he seems to be saying; once it was fire. Or, as Godard quotes Lubitsch in his recent short Letter to Freddy Buache: “lf you know how to shoot mountains, water and greenery you can also shoot people.”)

***

What drew me initially to their work, I must confess, is the particular stamp of their youthful cinephilia strictly as another one-time frequenter of the Cinémathèque Française and passionate fan of La Nuit du Carrefour and Scarface, Lang and Chaplin and Mizoguchi. For better and for worse, a particular tradition, which I have tried to outline in the selection of texts called “Straub and Huillet on Filmmakers They Like and Related Matters” — which may help to explain why I’ve omitted most of their negative comments about films and filmmakers they dislike.(For further material, the reader should consult the bibliography of interviews, scripts and other statements and texts by Straub-Huillet on the back cover of the March 1976 Monthly Film Bulletin, vol. 43, no. 506.)

Echoes of this tradition can be seen in the work of such contemporaries as Eustache, Rivette and Moullet. Examples abound: the direct evocations of Murnau in The Mother and the Whore, of Pandora and the Flying Dutchman in Mes Petits Amoureuses; the Hitchcockian doubling and inspirations of Hollywood cartoons and musicals in Celine and Julie Go Boating; or the special resonance given to the title of Moullet’s Les Contrebandières (The Smugglers) by the fact that the French title of Lang’s Moonfleet is Les Contrebandières de Moonfleet.

“Language is theft,” Moullet aptly pointed out to Roland Barthes in Pesaro in 1966,in reference to the language of Hollywood and its decadent derivatives. (See “A la Recherche du Luc Moullet: 25 Propositions” in the November-December 1977 Film Comment for further details about the least known of all the filmmakers in this season — and a figure whom one of my more starstruck colleagues once accused me of inventing.) This is only to say that the relations of Godard, Rivette, Eustache, Moullet and Straub-Huillet to commercial filmmaking are invariably dialectical, unlike the slobbering tributes, cribs and variations of Bogdanovich, Carpenter and De Palma (whom, even at their best, are never bringing critical perspectives to what they pilfer — merely simplifying them into formal diagrams).

The profound distrust and fear of the world that “the movies” bequeath to us in their alienated soundtracks and falsified images (see Moullet’s “Film is Only a Reflection of the Class Struggle,” below) is a tradition that Straub-Huillet’s films are designed directly to oppose, even though significant parts of that tradition are also being honored by them in this season — exceptional instances where the work of a Ford, a Renoir, a Hawks or a Lang can transcend these material limitations.

“No aspect of artistic creation is without a political basis for Straub and Huillet,” David Ehrenstein wrote recently (October 1, 1982) in the Los Angeles Reader. The list of films that they admire for this particular season is eccentric (3), yet anything but arbitrary. I can’t claim to know the reasons for the selection in every case. At a meeting with Straub and Huillet last spring, one of them (I forget which one) inadvertently cleared up my curiosity about the inclusion of Erich von Stroheim’s Blind Husbands (over, say, Stroheim’s Foolish Wives or Greed) with the simple remark that it was the only film of Stroheim’s in which Stroheim himself had control over the final editing. An obvious point, perhaps, in retrospect, but how many of us are so politically focused that the same reason for the selection might have occurred to us?

lndeed, all the choices of films by Straub and Huillet in this season can be called political choices, although some may be quasi-mystical as well. (See, for instance, the remarks about Lang’s Der Tiger von Eschnapur and Das indische Grabmal in section #6 of “Straub and Huillet on Filmmakers They Like. . .”) This doesn’t necessarily make their decisions simple-minded either. There are no “of courses” in this season that I can think of: the relation of Straub-Huillet to The Big Sky, for instance, is not immediately obvious. As with their own films, some form of work is required.

What remains essential to the controversy of their work is not their grasp of either politics or art — their sophistication about both is evident in much of what they say — but the precise point(s) at which their art and their politics intersect.

As an example of the impact that Straub-Huillet have made on the work of a wholly American artist, consider the testimony of Martha Rosler, interviewed by Jane Weinstock in October #17:

ROSLER: . . . I think my video has been influenced by the Straub-Huillet films. . . . At least I felt a strong sympathy when I saw them, but I don’t think I use film as they do. I’m not sure when I saw their work, but I’d be willing to admit either influence or similarity.

WEINSTOCK: In what aspect?

ROSLER: The aggressively self-conscious camera-work; the insistence that every movement counts; the way shots are edited together; a distanciation in acting; a cool, formalized relation to subjectivity — I always think of Gustav Leonhardt playing the harpsichord in the Bach film.

WEINSTOCK: What about your texts? They seem very dissimilar to those of Straub and Huillet.

ROSLER: Really? Including History Lessons?

WEINSTOCK: Yes. They use a preexistent text, one of Brecht’s.

ROSLER: Yet because of the firm’s meditative setting, it floats free of the narrative and becomes a philosophical text.

***

A couple of personal biases:

(1) Straub-Huillet. strike me as major filmmakers, but I certainly can’t pretend to accept their work without qualm or difficulty. Even after repeated viewings, the Bach firm seems to suffer from a certain academic exactness (of performance, of framing, of conception) that its many beauties fail to overwhelm for me. Some of the same problems may hound the more interesting lntroduction to Arnold Schoenberg’s Accompaniment to a Cinematographic Scene.

(2) Apart from Michael Snow’s La Région Centrale, I don’t know any more interesting films about landscapes than the last three Straub-Huillet features: Fortini-Cani, From the Cloud to the Resistance and Too Early, Too Late. But their relationship to history is antithetical to Snow’s in most respects, especially insofar as every site for them becomes the token (remnant, witness, symbol, pretext) of a political struggle. (Aside from the nationalistic, Canadian context of Snow’s structural epic, the landscape there is wholly other — undefined by any human presence, apart from the shadow of a computer-operated camera.)

An extraordinary facet of Too Early, Too Late: that it is the first Straub-Huillet film without characters, yet feels more populated than any of the others (chiefly in the second part). Hence the locations register as something more than tourist spots, as something much denser — places one has actually been, soaked with human presence.

***

One of the major political lessons of Straub-Huillet: that the anger of art and individuals can be just as implacable as the collective weight and inertia of institutions. Give me a moment as beautifully angry as the violent chop of water at the beginning of the pan in the last shot of Too Early, Too Late, and I think I can believe in the human will again, and in the force of nature too.

***

“A film that one shoots is always in the present”: Straub’s statement of an important agreement with Jacques Rivette about history (in section #19 of “Straub and Huillet on Filmmakers They Like. . .”) points to a significant aspect of all the texts in this publication — that they are all dated in very concrete ways. Thus the time of the first appearance of each is important to note. Luc Moullet’s article, published in Cahiers du Cinema in 1967, bristles with references to French rock and films of that period, as well as the French and American economies of the mid-Sixties. Gilberto Perez’s superb, lengthy study of Straub-Huillet — the real centerpiece of this collection, and the best account of their work in English that I know — was published over eleven years later in Artforum, at a point in their work when they were still only beginning their concentration on (mainly) rural landscapes which has dominated their subsequent features.

Tony Rayns’ synopsis and review of Every Revolution is a Throw of the Dice was written for the British Film Institute’s Monthly Film Bulletin in 1979, and follows that publication’s particular format in its division between an informational summary of a film’s contents and an interpretation/evaluation of those contents. Bruce Jenkins’ “Adaptation and ldeology: Two Films by Straub and Huillet” is adapted only slightly from a lecture given by the author in Buffalo at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in April 1981, as part of a four-part film-and-lecture series on contemporary European cinema. (To the best of my knowledge, these were the first American screenings of these films.)

My own “Transcendental Cuisine,” which is also about From the Cloud to the Resistance, written for (but not published by) Soho News in 1981, is perhaps the most mired in ‘local’ history of all the texts reproduced here, with specific references to both a column by Andrew Sarris that appeared in the Village Voice the previous week and a college course I was teaching at the time (as well as a 1962 essay by Manny Farber, “White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art”) although Serge Daney’s very beautiful and lighthearted “Cinemeteorology,” published in the Paris newspaper Liberation last February, begins with a reference to Blow Out, which opened in Paris the same week as Trop Tot, Trop Tard (Too Early, Too Late). Even the filmography, which is adapted and slightly expanded from one published in Paris around the same time — in conjunction with a retrospective at Studio 43 which inspired the present season — is limited and defined in part by information available to me in the summer and fall of 1982. (4)

A final word about the selection of texts for this booklet: the articles by Perez and myself are both included at Straub’s suggestion; Huillet suggested the Moullet article and sent me a copy of the piece by Daney; all the other editorial decisions are my own. Regarding the translations by myself and others, it should be noted that the occasional awkwardness of the language spoken (or written) by Straub and Huillet, while never consciously sought in any concerted way, was never consistently avoided either. Like the natural sounds and heavy accents heard in early sound films by Renoir such as La Nuit du Carrefour and Toni, this roughness is often only the by-product of an effort to be direct, accurate, honest and clear rather than slick or decorative.

For special and invaluable assistance in the preparation of this booklet and season I’d like to thank Fabiano Canosa (who literally made the whole thing possible), as well as Manny Farber and Patricia Patterson, Sandy Flitterman, Frederic de Goldschmidt of the cultural services of the French Embassy, Phil Mariani, Luc Moullet, Gerald O’Grady and Bruce Jenkins of Media Study/Buffalo, New Yorker Films, Joseph Papp, Gilberto Perez, Bérénice Reynaud (for help with the translations), Nancy Sher and Tony Safford of the American Film lnstitute, lngrid Scheib-Rothbart of New York’s Goethe House, Steven Soba (for advice, encouragement and help every step of the way), and Elliott Stein — not to mention Amy Taubin, whose assistance was entirely inadvertent, but who got me angry enough to want to launch this project….And, finally, Straub and Huillet themselves, who indirectly taught me how to put this anger to work.

J.R.

October 1982

1. 2012 footnote: Although the last thing I want to do here is reanimate any ancient feuds or quarrels, a couple of autobiographical notations may be of some relevance and/or interest here. (1) This retrospective was prepared during the year after I was fired from the Soho News, where my weekly film and book reviewing had formerly been my main source of income — accounting in part, I think, for some of the unusual and excessive belligerence shown here. (2) As one extreme example of the results of this belligerence, one of the editors of one of the film magazines I took a swipe at in this Introduction, who had previously shown me a lot of professional generosity and support, was so angry at this passing remark –- thinking it may have (or perhaps could have) caused a loss in that magazine’s state grant –- that seven years later, when I was scheduled to speak on his campus, he instructed or advised his students not to attend either of my lectures.

2. In the case of Moses and Aaron, it is simply not possible to appreciate certain directorial decisions unless one has read the stage directions in Schoenberg’s libretto, which Straub-Huillet simultaneously interpret and critique. For spectators who argue that this kind of work should be extraneous to The Aesthetic Experience — a cultural position that rules out T.S. Eliot and Antonioni while permitting Woody Allen and Fassbinder — a desired end product, not a process, is the point of aesthetics. Straub-Huillet’s utopian heresy: to present us with desired end-products in impossible times, times when it is impossible to cope with them, and then dare us to want to cope with them — intellectual striptease of a puritanical cast, pressed to agitational purposes.

3. Due to a shortage of programming space and/or lack of availability, four films selected by Straub and Huillet have been omitted from this season: Robert Bresson’s Journal d’un curé de campagne (Diary of a Country Priest), Howard Hawks’ The Big Sky, and Fritz Lang’s Der Tiger von Eschnapur (The Tiger of Eschnapur) and Das indische Grabmal (The Indian Tomb). For the record, their alternate choices were Lang’s Cloak and Dagger, Mizoguchi’s Miss Oyu and Street of Shame, and Moullet’s Les contrebandières (The Smugglers). In a similar season held in Paris last February, a few other selections were different: Chaplin’s City Lights, Abel Gance’s Capitain Fracasse, Mizoguchi’s Sansho Dayu, Renoir’s Une partie de campagne and Boudu sauvé des eaux.

4. Another 2012 footnote: I regret that I currently lack the means to reprint the remainder of this catalogue, but it’s worth noting that some of these texts are available elsewhere, including three of the four texts suggested for inclusion by Straub and Huillet: Perez’s seminal text was later adapted to form part of his seminal book The Material Ghost, the Serge Daney piece (in my own English translation) is posted here, and my own “Transcendental Cuisine” can also be found elsewhere on this site. More importantly, it’s worth pointing out that a long-overdue collection of this couple’s writings has just appeared in Paris, Écrits, published by Independencia Éditions — a pricey but very beautiful volume consisting of “Textes,” “Portfolio” (photographs taken and annotated by cinematographer Renato Berta), and “Atelier” (various work documents, with annotations by Straub). Go here for further details (and a couple of excerpts in translation).