From the Chicago Reader (June 12, 1992). — J.R.

HOUSESITTER

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Frank Oz

Written by Mark Stein and Brian Grazer

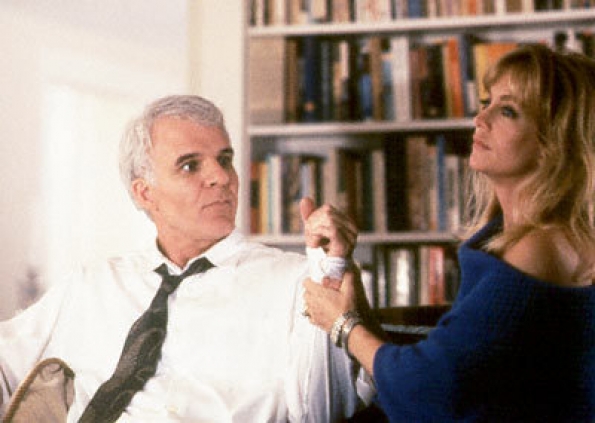

With Steve Martin, Goldie Hawn, Dana Delany, Julie Harris, Donald Moffat, Peter MacNicol, Richard B. Shull, Laurel Cronin, Roy Cooper, and Christopher Durang.

I’ve seen previews of two summer comedies so far — Sister Act and Housesitter — that have elicited gales of hysterical laughter from their mainly young audiences. In both cases the hysteria and volume of the laughter seemed a bit out of proportion. The one-joke premise of Sister Act — that there’s something indescribably hilarious about nuns behaving slightly irreverently — smacks more of quiet desperation growing out of repression than of something to feel happy about. I suspect that if I were a Catholic I’d feel more offended than charmed by the complacency of this running gag, whatever Emile Ardolino’s efficiency as a director. There’s a certain darkness behind many of the laughs in Housesitter, too, but at least they relate to a zeitgeist I can feel part of.

The main comic staple of Housesitter, apart from the enjoyable physical clowning of Steve Martin and Goldie Hawn, is a theme I associate especially with the comedies of Billy Wilder: the baroque complications that grow out of elaborate lies. The first Wilder examples that spring to mind are The Major and the Minor; Some Like It Hot; One, Two, Three; Kiss Me, Stupid; The Fortune Cookie; and Avanti!. The lies in these movies are about age, gender, politics, prostitution, physical injury, and adultery.

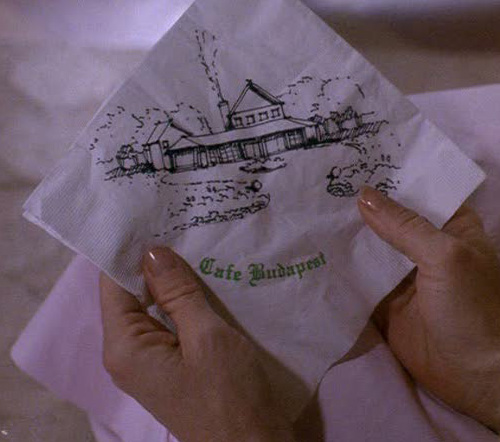

In Housesitter nearly all the lies relate explicitly to marriage and implicitly to class. But before we get to the lies, we’re treated to a prologue. Newton Davis (Steve Martin), an unfulfilled Boston architect, presents a literally gift-wrapped house he designed and built in their New England hometown of Dobbs Mill to Becky (Dana Delany), the woman he loves, as a marriage proposal, and she promptly turns him down. Three months later, still in love with Becky, he meets Gwen (Goldie Hawn), a waitress at a Hungarian restaurant in Boston, and spends the night with her in her apartment. That evening he shows her a sketch on a cocktail napkin of the house he built for Becky, noting that he hasn’t yet sold it and that it’s still standing there empty. End of prologue.

On her own initiative and without telling Newton, Gwen takes a bus to Dobbs Mill. Posing as Newton’s newlywed wife, she proceeds to fill the house with furniture and groceries that she charges to him, and meets Newton’s parents (Donald Moffat and Julie Harris) as well as Becky in the process. Newton eventually arrives with the intention of selling the house and is shocked by what Gwen has done; but he also discovers that Becky finds him more appealing as a newlywed and decides to keep up the masquerade as a means of wooing her.

Most of Gwen’s lies are outlandish improvisations that lead to other inventions. She tells Becky that she and Newton met in a hospital, that her face was all bandaged up because of a hit-and-run auto accident, and that they made love and even went through the wedding ceremony before the doctor removed the gauze. She also mentions that Newton paid her medical bills. When Becky, knowing that he had to borrow money to build their prospective dream house, asks her how Newton could afford it, Gwen invents another lie about Newton getting a promotion at his architectural firm.

Newton’s efforts to keep abreast of her inventions and add a few of his own have a lot to do with what keeps this movie cooking. The creative flights of fancy seem to work up a momentum of their own, and eventually even become a form of real wooing between the ersatz couple. The lie about the job promotion, for instance, gives birth to a whole series of lies that Gwen tells Newton’s boss (Roy Cooper) to try to get him that promotion; one of these is that her father from Ohio and the boss were in the same Army unit together. To back up this lie, she eventually has to recruit a couple of Boston street people (Richard B. Shull and Laurel Cronin) to play her parents when a wedding reception is held at the new house in Dobbs Mill.

Much of what makes this overall premise not merely funny but recognizable and even familiar is the fact that this country has been going through an extended period in which everything from the economy to the wars we wage is based on elaborate pyramids of deception, including ungainly amounts of self-deception — the way we’re encouraged to build our lives on credit and ignore portions of our own history represent only the tip of the iceberg. (The dream house Newton designs and builds on spec seems emblematic.) By proposing that our compulsive lie spinning is not only harmful, which we already know, but also sexy, creative, helpful, and therapeutic, Housesitter may simply be doing what most Hollywood comedies do: contriving to make us feel redeemed. But it also touches a portion of our psyches that we’re already pretty hysterical about; simultaneously guilt-ridden and defensive, we’re more than usually prone to responding with giddy laughter.

It’s gradually made clear that part of Gwen’s motive for her deceptions is a sense that she’s been excluded from things because of her class (“I just wanted to see what it would be like to live in that picture,” she says at one point to Newton, alluding to his sketch). But the film goes to great lengths not to spell this out in concrete detail. Hawn’s part is slender, though she’s a bit more adept than usual in finagling her way through it entertainingly. But at least her character isn’t cut short the way her false parents and Becky are by being defined exclusively according to a cliched notion of their respective classes.

As a mainly unsympathetic portrait of an upper-crust young woman, Delany’s Becky is certainly adequate as a foil for the two leads; but try to think about her character on her own terms and you can’t get very far. And Shull and Cronin’s characters are downright offensive because the movie seems to equate their homelessness with their alcoholism. That this movie seems happy to exploit this unexamined assumption is nauseating; but it’s also a crafty ploy that makes Gwen’s humble origins seem more respectable.

Steve Martin can’t do much with his character either, but only because he, like Robin Williams, seems to have forsaken some of the wilder aspects of his original comic persona for the blander, cornier characters that tend to figure in more commercially successful movies. (Similarly, Peter MacNicol makes Newton’s friend at work look and sound as much as possible like Billy Crystal, on the apparent assumption that familiarity breeds box-office receipts.) Fortunately, Martin has more success than usual drawing on his physical resources to give his uninteresting character some zany punctuations. Shortly after he enters his fully furnished house for the first time, he slips on the floor, falls over a sofa, and lands squarely on his feet with the kind of beautiful aplomb that, if memory serves, he last showed doing somersaults on a baseball field in Parenthood.

I suspect most of what makes Housesitter more watchable than anticipated is Frank Oz’s gradually developing grace as a comic director, also visible in What About Bob? and his hyperventilated use of Martin in Little Shop of Horrors. He can’t turn the dross in the script into gold, but he certainly gets the best out of his actors. (Too bad the script doesn’t allow more stretching room for Julie Harris, but wasting consummate pros tends to be standard operating procedure these days.) Oz also milks the most out of the comic situations, so as long as we aren’t reminded too insistently of the characters’ thinness, this is pretty funny and enjoyable stuff.