From the Chicago Reader (May 9, 2003). — J.R.

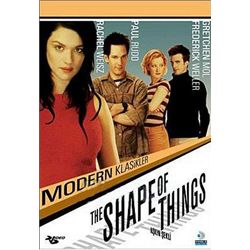

The Shape of Things

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Neil LaBute

With Rachel Weisz, Paul Rudd, Frederick Weller, and Gretchen Mol.

The first time I saw Neil LaBute’s The Shape of Things it packed a wallop. When I saw it again three weeks later it didn’t. Its force depends largely on a shock ending that transforms one’s sense of the characters, action, and overall theme with the authority of a masterpiece. Without this shock value, the film is still an infernal machine — designed, like LaBute’s In the Company of Men, to goad us into dark reflection — but its meanings tend to contract rather than expand.

Surprise endings either cancel out the impressions that come before, making the story seem contrived and artificial the second time around, or they enhance and complicate those impressions. The twist at the end of The Shape of Things comes closer to doing the first. The second time I saw it I felt I was watching the demonstration of a theorem more than the unraveling of characters, though it was only after having absorbed the disclosures of a first viewing that I became aware of certain interesting ambiguities.

I haven’t had a chance to find out how well Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne’s The Son, which also depends on a delayed plot disclosure, repays a second visit. I opted not to write about that film at length because I couldn’t imagine discussing it seriously without revealing its withheld point. I’ve decided to write about The Shape of Things despite my having to give away the ending because it’s the kind of film that properly starts only after it’s ended and therefore demands discussion as a whole, even more than The Son.

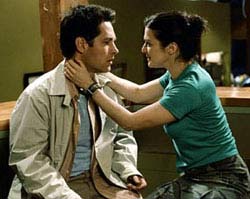

LaBute’s previous film, Possession, offered two tender love stories, one in the past and one in the present, both framed by a love of literature. The Shape of Things — initially written as a play during a break in the production of Possession, its dialectical opposite in every respect — offers one brutal tale about art framed by two interlocking failed-love stories. In Possession literature figured largely as a mode of seduction; in this film art is viewed almost exclusively as an assault. The two lead characters — there are only four characters in all — meet in an art museum in the first scene and in an exhibition hall in the last, and both sites are perceived from the outset as arenas for frontal attacks. In the first, Evelyn (Rachel Weisz), an outspoken and rebellious graduate student in art, is preparing to spray paint the fig leaf a bluenose committee has added to a male nude statue, and Adam (Paul Rudd), a meek undergraduate in English who’s working part-time as a museum guard, halfheartedly tries to dissuade her while asking for a date. (The way these two characters dress remains important throughout, presenting us with clues we’re asked to read as clichés — her Mao button and later her Che Guevara T-shirt, his corduroy jacket and the sportier jacket that eventually replaces it — and helping to shape a contrast with the other two characters.)

In the penultimate scene Evelyn reveals to a college gathering, including Adam and the other two characters, that her affair with Adam has been a cold-blooded work of “human sculpture,” undertaken as a thesis project and designed to remold her subject physically and to demonstrate how readily a male can agree to be remolded. In the final scene she meets Adam alone in a nearby exhibition hall where the tools, emblems, and documentation of her project are on display alongside a defiant banner reading “Moralists have no place in an art gallery,” a statement ascribed to Han Suyin, a contemporary Chinese-Belgian novelist.

The most vexing thing about the story in between — set mainly on campus lawns, in two apartments, in the lobby of a theater, and at a Starbucks– is that it comes across as two intertwining love stories, even though all the participants wind up single at the end, bereft of lovers and friends alike. The second couple, who are engaged when we first meet them, are Adam’s best friend and former roommate Philip (Frederick Weller), a self-satisfied jock whose friendship with Adam seems to have a touch of sadism, and the compliant Jenny (Gretchen Mol), whom Adam once had a crush on (furthering the sadism). After Adam spruces himself up and becomes more confident — he loses weight, stops biting his nails, changes his wardrobe, and replaces his glasses with contacts — Jenny kisses him impulsively, and he passionately reciprocates. Later, after Jenny confesses this indiscretion to Philip, Philip retaliates by telling Evelyn, who surreptitiously dips into Adam’s diary for more evidence, then stages a confrontation with Jenny and Adam that ends with Adam agreeing to give up both Philip and Jenny as friends. Still later, we discover that Philip and Jenny have broken off their engagement, then that Philip has proposed to Evelyn (even more outrageously, she reveals this in an aside during the public presentation of her human sculpture).

If this sounds a bit like farce — though practically none of it is played for laughs — it’s worth recalling that Restoration comedy was LaBute’s avowed inspiration for his first feature five years ago. In fact, The Shape of Things resembles In the Company of Men in many ways, though he’s shifted the gender of the predator and substituted art for business.

In the Company of Men concerns two businessmen plotting to break a woman’s heart for the sheer “fun” of it. The Shape of Things replaces the ruthless “fun” of business with the ruthless “edification” of art. That LaBute sees himself as something of a businessman artist, insofar as his films are business ventures as well as works of art, suggests he’s more than willing to implicate himself in the amoral machinations and ugly truths of his characters. He also wants to implicate us in Adam’s willing makeover of himself, challenging and testing us well before Evelyn’s revelation to see how much we approve of his actions in the name of love and self-improvement before we choke on the implications. In the final analysis, does love justify a nose job — which Adam at one point agrees to get — more or less than art does? Are these two different rationales for the same cruelty? What Adam does out of love for Evelyn comes dangerously close to self-hatred, and what she does to him in the name of art isn’t easy to distinguish from malice.

It’s to LaBute’s credit that he never keeps love and art entirely separate, even when he’s pretending to substitute one for the other. A key moment in Evelyn’s dispassionate, even icy, public presentation of her art project occurs when she speaks about Adam’s betrayal of her by kissing Jenny, and enough emotion creeps into her voice to suggest that she’s fighting back tears. She even reveals her suspicion that Adam and Jenny did more than just kiss — which makes us realize that maybe they did. Just because the scene between Adam and Jenny only shows them kissing doesn’t mean they didn’t have sex afterward.

This ambiguity is bolstered by a much more obvious ellipsis. In bed together early in their affair, Adam whispers something to Evelyn that we don’t hear. She whispers something equally inaudible back, and he grins. In the final scene she admits to him that during their affair everything she said and did was a lie — she even faked scars on her wrist to help persuade him to get a nose job — with one exception. She recalls that moment when she whispered to him in bed and says, “I meant that. I did.”

All this suggests that LaBute’s own piece of conceptual art isn’t quite as pure or conceptual as we may first suppose. Nearly every time Evelyn suggests ways Adam can revise his image he hesitates before complying. In that same bedroom scene he tells her, “It may be a touch early to start dictating who my friends are.” Similarly, Evelyn’s apparent calculations aren’t always as dispassionate as she claims; the sound of a woman scorned comes through unmistakably in her public presentation.

The most impressive thing about The Shape of Things is its shapeliness as a performance piece. Film adaptations of plays are usually expected to break free of their stage origins, but the concentration of this one in terms of space and focus is exemplary. Significantly, the sequence that uses the widest visual perspectives is the one in which Adam and Jenny negotiate their attraction to each other: toward the end of the scene we see a vista of cliffs, beach, and ocean behind them — at precisely the moment when their infidelity to their partners is most likely to grow. And the climactic moment when Evelyn’s voice cracks during her presentation — the other moment of intense ambiguity — takes place inside a cavernous auditorium.

Because this movie started out as a play with the same cast, all four actors have worked over every facet of their characters so carefully that each gesture and intonation has weight — nothing is an accident or a throwaway. LaBute has extracted the maximum amount of meaning from his material by letting us approach it from every possible angle, like a piece of sculpture. And this seems entirely appropriate given that the movie begins and ends with a presentation of and then an assault on a piece of sculpture — the first of which is stone and covered with a fig leaf, the second human and emotionally stripped bare.