This defense of what I consider Robert Altman’s most neglected major work appeared in the May 8, 1998 issue of the Chicago Reader. I’ve deliberately refrained from including any stills from Kansas City — its “parent” film, which I continue to dislike. — J.R.

Jazz ’34: Remembrances of Kansas City Swing

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Robert Altman

With Jesse Davis, David “Fathead” Newman, Ron Carter, Christian McBride, Tyrone Clark, Don Byron, Russell Malone, Mark Whitfield, Victor Lewis, Geri Allen, Cyrus Chestnut, James Carter, Craig Handy, David Murray, Joshua Redman, Curtis Fowles, Clark Gayton, Olu Dara, Nicholas Payton, James Zollar, and Kevin Mahogany.

The best Robert Altman feature in more years than I care to remember isn’t playing at a theater anywhere. A shortened version aired on PBS’s “Great Performances” series last year, but the movie only recently came to my attention when a video copy (distributed by Rhapsody Films) arrived in the mail. A fascinating adjunct to Altman’s much more ambitious and much less successful Kansas City (1996), Jazz ’34: Remembrances of Kansas City Swing is one of the best jazz films I’ve ever seen. It’s what its parent film promised but failed to deliver — all the more interesting because it’s neither a documentary nor a narrative but an eccentric hybrid.

Part of what made Kansas City so difficult was its ugly story, another piece of dime-store fatalism and knee-jerk crosscutting by a TV veteran who perversely falls back on that combo whenever he’s trying to be most personal (a long fall from sustained intuitive dreams like McCabe & Mrs. Miller, The Long Goodbye, and California Split, if firmly in the class of his formulaic roasts of capitalist greed and media foolishness). Part was how incidental the music turned out to be. And part was that the intermittently dreamy atmosphere was never allowed to build into anything (Altman’s poetry is mainly a matter of instinctive, improvisational meanderings that his bitter philosophy tends to interrupt or contradict). By contrast, the 75-minute Jazz ’34 alternately drifts and surges, without the interruptions of a gratuitous narrative. Better yet, it triumphantly demonstrates that atmosphere, music, and narrative can interact so well that it’s impossible to separate them.

This is rare in the history of the jazz film. As hyperbolic as it sounds, the last time it happened in a fiction film might have been in Dudley Murphy’s 21-minute masterpiece with Duke Ellington, Black and Tan, made on the cheap during the first year of talkies. Even the undeniable achievements of Round Midnight and Bird in recent years were undermined whenever their music and stories had separate agendas — the bane of practically every jazz film, documentary or fictional, that contrives to build a nonmusical narrative around the music.

Kansas City was simply the latest in a long line of features that use jazz the way Hamlet uses Rosencrantz and Guildenstern — as interruptions designed to be interrupted. Formally, Jazz ’34 might be said to relate to Kansas City the same way that Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead relates to Hamlet, but with a few important differences. Stoppard’s focus on background elements in a tragic melodrama is alienated and absurdist; Altman’s absorption in their equivalents — musicians jamming in a nightclub at various times of day and night — is neither alienated nor absurdist and is far from melodramatic, a rare departure for Altman.

Properly speaking, Altman’s model is not Black and Tan, which has a fairly nuanced tragic tale to tell between and through its music interludes. Nor is it any of the straight jazz documentaries — a less problematic tradition represented at its most distinguished by The Last of the Blue Devils (1979), a 90-minute account of a reunion of key Kansas City musicians filmed by Bruce Ricker, who later went on to found Rhapsody Films, the premier jazz-on-film video label. Ricker told me that Altman’s conscious cinematic model for Jazz ’34 was Jammin’ the Blues, a classic ten-minute short directed by Life magazine photographer Gjon Mili in 1944 — a documentary of a real jam session set inside a fictional space.

Released by Warner Brothers and shot in black and white by Robert Burks (who went on to become the cinematographer for most of Alfred Hitchcock’s masterpieces in the 50s and 60s), Jammin’ the Blues opens with one of many arty effects: a dim abstract form resembling a bull’s-eye wreathed in cigarette smoke tilts to become the top of Lester Young’s porkpie hat, as he improvises a slow, relaxed blues over a soft rhythm section. A nameless narrator informs us, “This is a jam session. Quite often these great artists gather and play — ad lib — hot music. It could be called a midnight symphony.” Throughout this number and two succeeding ones an assembly of first-rate musicians plays within a highly abstract and mutable space, usually against backdrops that are either all white or all black, posed in various combinations with a stiff jitterbugging couple to create striking configurations in chiaroscuro, silhouette, and multiple exposure. As pretentious as some of it looks, it sounds fabulous, and a few of the images — such as Young’s tenor sax cradled in his lap and arms like a swan — are unforgettable.

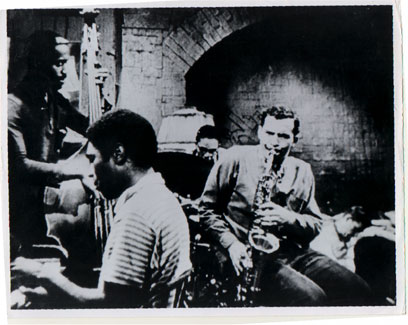

Jazz ’34 opens with a slow track across the street from a re-created block of 30s Kansas City storefronts spotted with period extras. The camera then approaches and enters the Hey Hey Club, while an offscreen Harry Belafonte informs us that 1934 was “when Kansas City defined the word ‘swing.’ Jazz that was sophisticated, but with a rough-and-tumble spirit Kansas City thrived on. Count Basie, Mary Lou Williams, Hot Lips Page, Ben Webster — greats of jazz gravitated to Kansas City in the 30s, when the scene was wide open and jazz was happening round the clock. Cats came to play. They were really outplaying each other in legendary cutting contests. Like the time Coleman Hawkins and Lester Young locked horns in a battle of the tenors” (which inadvertently evokes a famous scene from Bambi).

“Robert Altman grew up in Kansas City and remembers the music of joints like the Hey Hey Club,” Belefonte continues. “He’s re-created a classic jam session with some of the best musicians of today playing in the spirit of the pin-striped suits — the jazz legends of yesterday. Like those cats in the 1930s, these cats of today came to swing — in Kansas City.” By this time a loose cluster of layabouts in period costume in the general vicinity of the bar are ready to start playing. They launch into “Tickle Toe,” a Lester Young tune, and the film is firmly under way.

Even if parts of the preceding narration sound more strained than the verbal introduction to Jammin’ the Blues — is “cats” really the best way to describe 1934 musicians? — the creation of a fictional space for the music is at once more confident and less pretentious. Some ornamental women are around to dance and beat out the time just as self-consciously as Mili’s jitterbugging couple, and subsequent voice-overs by unidentified individuals contribute the same sort of blather about the music (though also a few facts and some atmosphere). But none of this matters much, because the playing is often mesmerizing and it always swings.

To what extent are these musicians “playing” themselves, and to what extent are they playing fictional 30s counterparts? Many of the players clearly suggest 30s figures: Geri Allen, the piano player on “Tickle Toe” and several other numbers, is meant to evoke Mary Lou Williams, and when Cyrus Chestnut turns up on the keyboard he’s an evident stand-in for Count Basie — at least until he plays a solo with a few Fats Waller embellishments on “Queer Notions,” a Coleman Hawkins tune. Kevin Mahogany as a singing bartender is designed to conjure up memories of Joe Turner, and two figures evoke Charlie Parker — a 13- or 14-year-old seated in the balcony with his alto sax (who appears as Parker in Kansas City) and a sax player with the same build as the adult Parker, who solos on several numbers, sounding most like Parker (during his early stint with Jay McShann) on “Moten Swing.” And when the jam session culminates in a wonderful climactic “cutting” session between tenor sax players Craig Handy and Joshua Redman, the obvious reference point is the legendary match between Hawkins and Young, already signaled by a poster on the front door of the club.

But Ricker told me that Redman wasn’t informed until after the number was over that he was supposed to be Young, so any distinction between acting and being — or between impersonation and self-expression — can’t be precisely drawn. (Redman’s first solo incorporates a few Young-like licks, but given the number and the instrument he’s playing, this is far from surprising.) The function of all of these reference points is to provide a few tentative guidelines for how we relate to the music, even if some of the tunes (such as Ellington’s “Solitude”) and individual phrases aren’t germane to Kansas City swing. Is it likely or even possible that the tenor sax player who quotes from “Exactly Like You” in his “Moten Swing” solo would have made such an allusion in 1934? As a child of the bebop era who hasn’t even read Ross Russell’s Jazz Style in Kansas City and the Southwest, I can’t say. But my point is that one can’t always expect the musicians’ sense of musical history and their freedom as improvisers to be a perfect fit.

What’s more important — at least for those of us born well after 1934 — is to feel our way into the period intuitively and speculatively, along with the musicians. Making a film that’s more interested in launching this project than in monitoring it in academic terms is an awesome existential endeavor, and it’s central to what makes Jazz ’34 such a thrilling experience. Any improvisation implies a balance between memory (remembered riffs and phrases, conventions and chord changes) and creativity, between inherited text and invention; the same thing could be said of the live performances of actors in most narrative fictions, which frequently depend on re-creating a text according to the unforeseeable vicissitudes of a given climate, mood, and moment. Though they’re dressed in 30s clothes and playing 30s swing inside a 30s set — or rather a Kansas City location dressed like a 30s set — the musicians in Jazz ’34 are also 90s figures performing in the 90s; the degree to which they’re acting or reacting, inventing or remembering, discovering themselves in the past or in the present is never fixed. They’re not alone; we too must continually reassess the extent to which we’re watching a period re-creation or a contemporary jam session.

This same idea was touched on in Altman’s 1991 taping of Black and Blue, a brassy all-black, 20s-style dance and musical revue on Broadway (a video aired on PBS in 1993), but this earlier foray has none of the excitement of Jazz ’34. Altman taped those proceedings with a live audience and took the novel approach of following the performers in their 20s costumes on- and offstage during the show. His restless camera work and editing keep changing our vantage point, so we’re never entirely with the audience or with the performers but in some intermediate realm. The characteristics of the live audience — including the number of its members that are black or white — are never allowed to register, and we scarcely learn any more about the backstage identity of the performers, though the mobility of Altman’s cameras teases us with the notion that we’re getting an insider’s view. (The program ends with a seemingly impromptu backstage continuation of the dancing after the curtain calls, ostensibly performed by the cast for their own amusement.)

I suspect that Black and Blue is truer to the music of the 20s than Kansas City and Jazz ’34 are to that of the 30s, but I can’t say I enjoyed it any more as a consequence; in fact, I liked it much less. The problem is the material as it’s packaged for Broadway rather than the talents of the performers: Black and Blue is jazzy and bluesy without ever qualifying as jazz or blues, whereas Jazz ’34 offers the genuine articles in spite of a postmodernist grasp of its period. Altman’s backstage notations for Black and Blue are just about the only thing about it that I find bearable.

A much more apt reference for Jazz ’34 might be the members of Jackie McLean’s jazz quartet playing drug addicts performing several hard-bop numbers in the Living Theater’s 1959 production of Jack Gelber’s The Connection. To increase the audacity of this move, McLean and the members of his rhythm section kept their own names in the play’s dialogue, so the degree to which they were simply expressing themselves when they improvised and the degree to which they were fleshing out Gelber’s fiction was something no one could determine with absolute confidence, including the musicians. (The same ambiguity can be found in Shirley Clarke’s 1961 film of The Connection, available on video; the same musicians are cast in the same parts, though the effect of addressing a live audience is missing.)

The crucial difference, in other words, is the improvising. Scoring of music and gesture can be found in both Black and Blue and Jazz ’34, but improvisation is negligible in the former (apart from the mise en scène) and central in the latter. So the fidelity of Black and Blue to 20s music doesn’t allow me to enter an imaginary 20s space, because the elements that go into producing a 90s Broadway musical revue overwhelm any inclination one might have to fantasize about the period. (Both Black and Blue and Jazz ’34 have figures rather than characters, but only the latter has a consistent setting that qualifies as an actual location.)

Jazz ’34 does have a loose, episodic narrative — moving from early morning to night to dawn to what appears to be late afternoon — and even a certain moral development (though this needs to be explicated because the commentary contradicts it). Insofar as Kansas City represents the repressed, “buried” text in Jazz ’34 — much as Jazz ’34 represents the “buried” text in Kansas City — it’s worth considering what this text signifies. The ruthlessness of capitalism is an important part of that meaning, and the competitive aspect of the “battle of the tenors” gives it a precise musical form; the female narrator we hear immediately after this battle underlines the connection: “They had cuttin’ contests like they was gunfighters. Kansas City was the only place where the musicians battled it out with all guns blazin’.”

If the climactic musical “duel” actually matched her description, the scene might have unfolded like the famous pissing contests between Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie on their brilliant, if often unpleasant, Jazz at Massey Hall album (1953). But everything I know about Hawkins and Young suggests that they were much more supportive than competitive. Young, for instance, was nicknamed “Prez,” but he suggested many times that Hawkins deserved that label more. Hawkins showed an equivalent generosity. What we see and hear in the final number of Jazz ’34 is something that begins as a standoff — with the two tenors standing several yards apart, like those Bambi bucks preparing to charge — and ends with the two of them approaching each other and falling into a friendly duet, shaking hands as soon as the number’s over.

The rhetoric of capitalist culture often makes the best jazz sound more aggressive and competitive than it is, describing every love match as if it were a duel to the death. Altman does this himself whenever he turns away from the discoveries of his improvisational style. Here that denial is apparent only in the narration (in Kansas City it was apparent in just about everything). If you listen to the exchanges and duets of such giants as Warne Marsh and Lee Konitz you hear accommodation, interaction, and mutual discovery, not any sort of one-upmanship. If you listen, for that matter, to most of the music in this movie — not only Allen and Chestnut’s duet on “Piano Boogie,” but virtually every number — you hear the same thing. As if to clinch this point, Altman concludes his film with another duet, this one ostensibly tender, between bassists Ron Carter and Christian McBride, ironically playing “Solitude.” It’s a very different message from the one delivered in Kansas City, and Altman, going with the flow for a change, makes it look and sound a lot more believable.