From the Chicago Reader (October 6, 1989). — J.R.

THE LITTLE THIEF ** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Claude Miller

Written by Annie Miller, Claude Miller, and Luc Beraud

With Charlotte Gainsbourg, Didier Bezace, Simon de la Brosse, Raoul Billerey, and Chantal Banlier.

The French cinema has perhaps never been more desperately in the doldrums than now, and this slump is best represented by the trips down memory lane that seem to be a major preoccupation in current French movies. Never entailing research or reevaluation, these simplified, nostalgic foreshortenings of the past often pare away much of what makes that past interesting.

Claude Miller’s The Little Thief (La petite voleuse) is a case in point because it purports to be, at least in this country, the last work of the late Francois Truffaut. (I’m told that no such claims were made about the film when it opened in France, and can understand why; even French amnesia doesn’t ordinarily extend quite as far as our own.) The film was developed out of a long-nurtured Truffaut project that Truffaut considered filming at various points throughout his career; a 30- or 40-page treatment (accounts differ) he wrote with Claude de Givray served as Miller’s starting point, although by all accounts this story has been extensively reworked and embellished, and even given a new ending. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, November 1976, Vol. 43, No. 514. — J.R.

Ultima Donna, L’ (The Last Woman)

ltaly/France, l976

Director : Marco Ferreri

Cert—X. dist–Columbia.Warner. p.c—Flaminia Produzioni Cinema (Rome)/Les Productions Jacques Roitfeld (Paris). p—Edmondo Amati. p. managers–Maurizio Amiti, Roberto .Giussani. asst. d—Enrique Bergier, Bernard Grenet. sc–Marco Ferreri, Rafael Azcona, Dante Antelli. story–Marco Ferreri. collaboration on dial–Noël Simsolo. ph—Luciano Tovoli. col—Eastman Colour. ed–Enzo Meniconi. a.d—Michel de Broin. m—Philippe Sarde. m.d—Hubert Rostaing. cost—Gitt Magrini. sd. ed— Gina Pignier, sd. rec–Jean-Pierre Ruh. l.p—Gérard Depardieu (Gérard), Ornella Muti (Valérie), David Biggani (Pierrot), Michel Piccoli (Michel), Renato Salvatori’ (René), Giuliana Calandra (Benoîte), Zouzou (Gabrielle), Nathalie Baye (Girl in Shopping Mall), Soulange Skyden (Girl at Night-club), Carole Lepers (Anne-Marie), Daniela Silverio (Jane), Vittorio Ganfoni (Policeman with Dogs), Guerrino Totis. 9,799 ft. 109 mins. French dialogue; English subtitles.

French title—La Dernière Femme

Gérard, a young engineer whose wife, Gabrielle, has recently left him, meets Valérie, the attractive teacher at the factory nursery where he goes to collect his thirteen-month-old son Pierrot, and invites her home with him; she agrees, and is assured by her lover Michel thathe won’t interfere. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 1, 1989). — J.R.

Gabriel Axel’s Danish feature, the 1987 Oscar winner for best foreign film, is based on an Isak Dinesen tale. On the whole, the adaptation is faithful but some of the qualities of Dinesen’s language are lost in translation or through abridgment, and the politics have been needlessly simplified. The plot concerns a French servant in a strict Lutheran household in Denmark — Norway in the original — whose family has perished in the French Commune uprising. The acting is impeccable and the ambience suffused with delicate charm, but overall this doesn’t aim at anything higher than Masterpiece Theatre or a Merchant-Ivory film. Aside from the elaborate serving of the eponymous meal, which expands greatly on the original, few of the additions constitute improvements. With Stephane Audran, Jean-Philippe Lafont, Jarl Kulle, Bodil Kjer, and Birgitte Federspiel (Ordet). In Danish with subtitles. 102 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 1, 1989). — J.R.

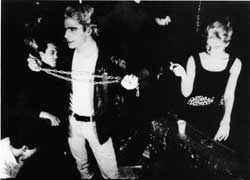

After paying $3,000 for the rights to Anthony Burgess’s novel A Clockwork Orange, Andy Warhol made this very loose adaptation (1965) using direct sound, with such Warhol regulars as Ondine and Edie Sedgwick, Gerard Malanga performing a whip dance, and music by the Velvet Underground. It’s one of Warhol’s very best — and most painterly — films, more interesting for what it does with crowded space than for the S and M. 64 min. (JR)

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (August 12, 2005). — J.R.

Last Days

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed and written by Gus Van Sant

With Michael Pitt, Lukas Haas, Asia Argento, Scott Green, Nicole Vicius, Ricky Jay, and Thadeus A. Thomas.

A film about a junkie rock musician, played by Michael Pitt at his most narcissistic, doing nothing in particular for the better part of 97 minutes isn’t my idea of either a good time or a serious endeavor. Yet a few of my colleagues seem to be responding to Gus Van Sant’s Last Days the way some responded to The Passion of the Christ — taking it without a grain of salt or an ounce of irony. But it’s the grunge version of the Christ story, so that makes it hip.

Manohla Dargis of the New York Times writes that it’s about the “resurrection of Gus Van Sant,” the “mystery of human consciousness,” the “ecstasy of creation,” and “how sorrow sometimes goes hand in hand with the sublime.” Even a compulsive jokester like the New Yorker‘s Anthony Lane sounds like he just stepped out of Sunday school, writing, “Some of the motion has a hypnotizing grace,” and when the camera retreats from a house where Blake (Pitt) is noodling distractedly on his guitar, “We might as well be overhearing him at prayer.” Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 19, 1995). — J.R.

Mamma Roma

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Pier Paolo Pasolini

With Anna Magnani, Ettore Garofolo, Franco Citti, Silvana Corsini, Luisa Orioli, Paolo Volponi, Luciano Gonini, Vittorio La Paglia, and Piero Morgia.

Who can predict the changes in intellectual fashion over 20 years? In 1975, when the controversial Italian writer and filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini was brutally murdered by a 17-year-old boy in a Roman suburb, he was no more in vogue than he had been throughout his stormy career. If any openly gay writer-director was an international star in the mid-70s, it was Rainer Werner Fassbinder, who at that point was spinning out as many as three or four features a year; he died in 1982 after an orgy of cocaine abuse.

Pasolini and Fassbinder were both maverick leftists who often alienated other leftists as well as everyone on the right, and both had a taste for rough trade, but in terms of their generations (Pasolini was born in 1922, Fassbinder in 1946) and cultural reference points they were radically different. The only reason to compare them now is to note how much their reputations and visibility have changed here over the last two decades. Read more

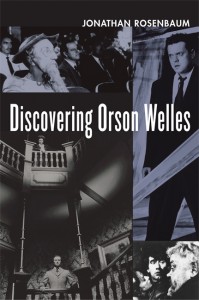

Written in late 2006 and published in Discovering Orson Welles the following year. — J.R.

The process-oriented methods that permitted at least four Welles features and a number of short works to be left unfinished are easier to understand than they would be if we adopted the mental habits of producers, which is exactly what more and more critics today seem to be doing; but that is no comfort to those of us eager to understand, and eager as critics always are to have the last word, which we are not about to have with this filmmaker. At least our direction, as always, is laid out for us: as long as one frame of film by the greatest filmmaker of the modern era is moldering in vaults, our work is not done. It is the last challenge, and the biggest joke, of an oeuvre that has always had more designs on us than we could ever have on it.

Bill Krohn’s cautionary words in Cahiers du cinéma’s special “hors série” Orson Welles issue in 1986 offer a useful motto for the present collection of essays, whose own title, Discovering Orson Welles, suggests an ongoing process that necessarily rules out completion and closure — the two mythical absolutes that Welles enthusiasts and scholars seem to hunger for the most. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 22, 2002). — J.R.

Monster’s Ball

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Marc Forster

Written by Milo Addica and Will Rokos

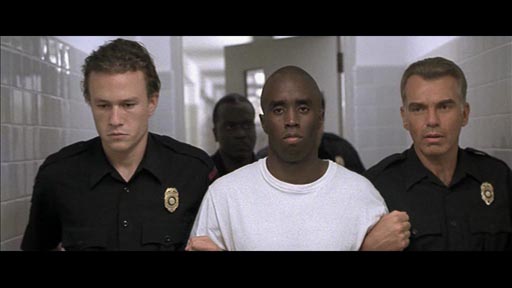

With Billy Bob Thornton, Halle Berry, Peter Boyle, Heath Ledger, Sean Combs, Mos Def, and Coronji Calhoun.

Monster’s Ball is a Hollywood art movie; even the fancy color graphics imposed on the seedy milieu behind the opening credits tell us that. For some viewers, including a few reviewers, the movie becomes bearable only after an hour of misery, when the lead characters, Hank Grotowski (Billy Bob Thornton) and Leticia Musgrove (Halle Berry), finally get around to having their big sex scene (which I have to admit is worth the price of admission). Maybe the sex is prompted by these characters’ mutual misery, but it also happens because this is a Hollywood movie and these are its stars. And because it’s also an art movie, all the misery preceding the scene makes it feel earned.

Hank is a white corrections officer at the state pen in Georgia who recently guided Leticia’s husband, who’s black, to the electric chair, though it takes him a long time — and her even longer — to figure out the connection. Read more

From the August 1, 2001 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

If, like me, you’ve been wondering how Terry Zwigoff, the brilliant documentary filmmaker who made Crumb, would negotiate his shift to fiction filmmaking, here’s your answer: brilliantly. Ghost World, a very personal adaptation of the Daniel Clowes comic book that Zwigoff wrote with Clowes, either captures with uncanny precision what it’s like to be a teenage girl in this country at this moment or fooled me utterly into thinking it does. Thora Birch (American Beauty) plays Enid, a comic book artist (her notebook was actually drawn by Sophie Crumb, Robert’s daughter) who plans to share an apartment with her best friend Rebecca (Scarlett Johansson). Enid befriends Seymour (Steve Buscemi), a lonely, much older collector of rare blues and jazz 78s, shortly after she almost graduates from high school. To get a diploma, she has to take an art course over the summer, and our glimpses of this add up to the funniest portrait of American “art appreciation” I’ve ever seen, with Illeana Douglas, as the teacher, rivaling Elaine May as a satirist. Never predictable, this movie is often hilarious as well as touching, subtly adapting the mise en scene of Clowes’s original without being fancy or obtrusive about it. Read more

My 1973 Cannes coverage for London’s Time Out (which ran in their June 8-14 issue, about a year before I moved to London from Paris), slightly tweaked. I’m pretty sure I submitted something longer and more detailed (judging from my penultimate sentence, my account of Jerry Schatzberg’s Scarecrow must have been one of the several things that was cut), but I no longer have the original version to verify this. — J.R.

May 11: Discounting Godspell, the opening film, which I avoided seeing yesterday both for its sake and for mine, the festival got off to a rousing start today with two strong and absorbing films.

Joseph Losey’s A Doll’s House -– shown in the official festival, out of competition — cannot however be considered a successful embodiment of the Ibsen play. The authorial agendas of Ibsen, Losey, and [Jane] Fonda ultimately diverge more than combine, and we arrive at an abrupt impasse – a torso of the play that’s still missing a head.

‘To waken the sleeping beauty,’ says a carnival barker in James B. Read more

From the January 15, 1999 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

The Thin Red Line

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Terrence Malick

With Sean Penn, Adrien Brody, Jim Caviezel, Ben Chaplin, John Cusack, Woody Harrelson, Elias Koteas, Nick Nolte, John C. Reilly, Arie Verveen, Dash Mihok, John Savage, John Travolta, and George Clooney.

Last week the National Society of Film Critics voted Out of Sight the year’s best picture, also awarding it best screenplay and best direction. If this baffles or bemuses you, you should know that the awards in each category are chosen by multiple ballots listing three titles in order of preference. What now seems like a collective preference for a sexy thriller over more ambitious pictures was in effect a tie-breaker between two irreconcilable positions.

As a participant in the meeting I saw partisans of Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan square off against partisans of The Thin Red Line, Terrence Malick’s first film since Days of Heaven (1978). Practically no one voted for both — only Michael Wilmington of the Chicago Tribune comes to mind — so Steven Soderbergh lurched forward as a second choice, finally copping 28 votes while Spielberg and Malick tied for second place with 25 votes apiece. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, January 1975 (Vol. 42, No. 492). -– J.R.

The Projectionist

U.S.A., 1970

Director: Harry Hurwitz

Chuck, a stocky film projectionist who works in midtown Manhattan, hears on a radio about an old man mugged on the Lower East Side, and imagines himself coming to the rescue as Captain Flash. The reverie is broken off by the arrival of his friend Harry, an usher, who hears him describe meeting a pretty girl on the way to work (provoking a romantic-movie pastiche); this is interrupted in turn by Renaldi, the tyrannical theatre manager, who orders Harry out of the booth. Chuck next fantasizes a preview,’The Terrible World of Tomorrow”, before getting off work. As Captain Flash, he loses a fight with the thugs, and the old man informs him that The Bat is after his death ray; they proceed to The Bat’s hideout, where Flash sees the same pretty girl he had described to Harry. In the cinema lobby, Chuck chats with the Czech candy man, who is eventually reprimanded by Renaldi for giving Chuck free lemon drops from the counter. Chuck imagines another preview (“The Wonderful World of Tomorrow”) and a Flash episode in which he visits ‘Rick’s Bar’ in Casablanca and tangles with a prehistoric beast in The Bat’s cave. Passing a movie premiere, he imagines arriving there as a celebrity. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (November 13, 1998). It seems like there are some cinephiles around who still regard Dogme 95 as an honest-to-Pete aesthetic position and not as a lucrative business, ignoring that as far back as 2000, official Dogme Certificates were being sold in Denmark for roughly $1,000 apiece — apparently as a adjunct to von Trier’s main form of income, his ongoing porn-film business (which has also been widely ignored). — J.R.

The Celebration

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Thomas Vinterberg

Written by Vinterberg and Mogens Rukov

With Ulrich Thomsen, Henning Moritzen, Thomas Bo Larsen, Paprika Steen, Birthe Neuman, Trine Dyrholm, and Helle Dolleris.

In 1961 we wrote this manifesto of the New American Cinema. Eugene Archer was working for the New York Times then, and I showed it to him and asked him if they could print it. He said, ‘No, we couldn’t — maybe the Village Voice could run it.’ Then I understood, of course, that the only kind of manifesto that the New York Times would print would be a press release, not a manifesto at all. In the same way, for an idea to get into the Village Voice today, it has to become not an idea but something else. Read more

From Oui (August 1974). — J.R.

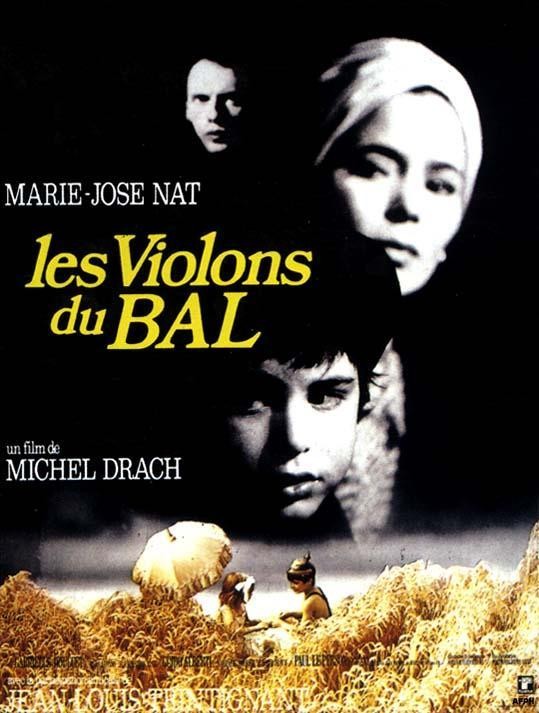

Violins at the Ball. It appears that the two obsessive themes of French cinema right now are movies about movies and movies about the German Occupation. Michel Drach’s Violins at the Ball combines both of these, but on a very personal level, for the story he has to tell is Drach’s own. It is told in two tenses: a present in black and white showing Drach as he tries to interest a producer in his film and he travels around Paris and Oise with his cameraman; a past in color that he is filming, which describes his adventures as a Jewish child during the Occupation.Drach’s wife, actress Marie-José Nat, plays herself in the present and his mother in the past, while their son David portrays Michel at the age of eight. To complicate matters further, the producer declares that the film can’t be made without a star, and Drach immediately replaces himself with Jean-Louis Tringtignant – who also happens to be his best friend. Drach has wanted to make this film for 15 years, and it shows in the careful attention given to various details, the subtle transactions between memory and invention, fear and comfort, yesterday and today. Read more

Curiously, the Chicago Reader’s web site dates this capsule review in October 1985, two years before the film was made. I first saw it at the Toronto Film Festival in September 1987, and believe I reviewed it not too long afterwards. — J.R.

Norman Mailer’s best film, adapted from his worst novel, shows a surprising amount of cinematic savvy and style from a writer whose previous film efforts (Wild 90, Beyond the Law, Maidstone) were mainly unvarnished recordings of his own improvised performances. Working for the first time with a mainstream crew and budget and without himself as an actor, he translates his high rhetoric and macho preoccupations (existential tests of bravado, good orgasms, murderous women, metaphysical cops) into an odd, campy, raunchy comedy thriller that remains consistently watchable and unpredictable — as goofy in a way as Beyond the Valley of the Dolls. Where Russ Meyer featured women with oversize breasts, Mailer features male characters with oversize egos (although the women here also do pretty well in that department), and thanks to the juicy writing, hallucinatory lines such as “Your knife is in my dog” and “I just deep-sixed two heads” bounce off his cartoonish actors like comic-strip bubbles; even his sexism is somewhat objectified in the process. Read more