This was originally published in the January 22, 1988 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

HOUSEKEEPING **** (Masterpiece)

Directed and written by Bill Forsyth

With Christine Lahti, Sara Walker, Andrea Burchill, Anne Pitoniak, Margot Pinvidic, and Bill Smillie.

Two or three days and nights went by; I reckon I might say they swum by, they slid along so quiet and smooth and lovely. — The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Marilynne Robinson’s novel Housekeeping is virtually defined by its slow, swirling rhythms, but one of the first things that is apparent about Bill Forsyth’s passionate, faithful film adaptation is that, as story telling, it starts out with a hop, skip, and jump; and although an idea of leisurely pacing is sustained throughout, the movie never dawdles, stalls, or grinds to a halt. Like the magical opening of Terrence Malick’s 1973 Badlands and the no less incandescent ending of his 1978 Days of Heaven –- two more films in which the heroine’s offscreen narration plays a musical role in the narrative structure -– the story unfolds with the combined immediacy and remoteness of a fairy tale. An elliptical stream of details and events spanning three generations flows by in minutes, without imparting any feeling of haste. Read more

From the July 21, 1989 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

LET’S GET LOST ** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Bruce Weber.

“Can you carry a tune? Is your time all right? Sing! If your voice has hardly any range, hardly any volume, shaky pitch, no body or bottom, no matter. If it quavers a bit and if you project a certain tarnished, boyish (not exactly adolescent, almost childish) pleading, you’ll make it. A certain kind of girl with strong maternal instincts but no one to mother will love you. You’ll make it. The way you make it may have little to do with music, but that happens all the time anyway.”

This is jazz critic Martin Williams 30 years ago in a Down Beat review of It Could Happen to You: Chet Baker Sings. By this time, the youthful Baker had already established a reputation as a jazz trumpeter of some promise, and later in the same review, Williams concedes that as an improvising musician, he has a “fragile, melodic talent” that is “his own,” even if he “has hardly explored it.” The same strictures might apply to Let’s Get Lost, Bruce Weber’s spellbinding (if simpleminded) black-and-white documentary about the life, times, and last days of Chet Baker. Read more

From the September-October 1978 issue of Film Comment. — J.R.

An Altman

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Doubling the number of featured players in Nashville from twenty-four to forty-eight while shrinking the time scale from three days to one, A Wedding offers an extension rather than an expansion of Robert Altman’s behavioral repertory. Variations on the same dirty little secrets, social embarrassments, and isolating self-absorptions that illustrate his last ten movies are trotted out once again -– articulated as gags or tragicomic mash notes, molded into actors’ bits, arranged in complementary or contrasting clusters, orchestrated and choreographed into simultaneous or successive rhythmic patterns, and strategically timed and placed to coincide with unexpected plot or character reversals.

The execution of these pirouettes has never presented critics with much of a problem, for the level of craft is pretty consistent. (Some gags are funnier than others, but all get the same careful/offhand inflection.) What remains a bone of contention is their justification, which shifts more discernibly from film to film. M*A*S*H’s was that war could be fun while Brewster McCloud’s said that escape was impossible; Images and 3 Women depended on shopworn arthouse symbols while Nashville and Buffalo Bill and the Indians put the American flag to comparable use. Read more

Whoever said that cinema and film criticism aren’t international languages?

http://apaladewalsh.com/2014/06/15/joao-benard-da-costas-johnny-guitar-play-it-again-in-nine-tongues/

[6/16/14] Read more

From the October 23, 1992 Chicago Reader. This represents my very first attempt to write about Kiarostami’s cinema in a longer review, while I was still beginning to get acquainted with it, and I very much regret my serious underestimation of Where is The Friend’s House? (whose title I and others also got wrong at the time). On the matter of Tati and Kiarostami, Kiarostami has always denied having heard of him whenever I’ve brought up the name, but his former collaborator Amir Naderi affirmed that Kiarostami certainly knew who he was, having been present at the Children’s Film Festival in Tehran when Tati headed the jury there in the mid-1970s (and in fact, I was reminded by Amir’s remarks that Richard Combs, my boss at the time in London, served on the same jury). In fact, I’ve learned from Ehsan Khoshbakht that this festival was sponsored by Kanun, where Kiarostami was employed at the time. — J.R.

AND LIFE GOES ON . . . (LIFE AND NOTHING MORE)

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed and written by Abbas Kiarostami

With Farhad Kheradmand and Pooya Pievar.

It’s fascinating to consider the ideological factors that influence how film canons are formed, especially when it comes to films that depict unfamiliar cultures. Read more

As far as I know, this is the only long review of mine for the Chicago Reader that isn’t on the Reader‘s web site, and consequently it wasn’t on this site, either, until I retyped it for inclusion here. It appeared in their May 17, 1999 issue. It’s also one of the pieces selected and translated into Farsi by Saeed Khamoush for the unauthorized collection of some of my Reader pieces that was published in Iran back in 2001. — J.R.

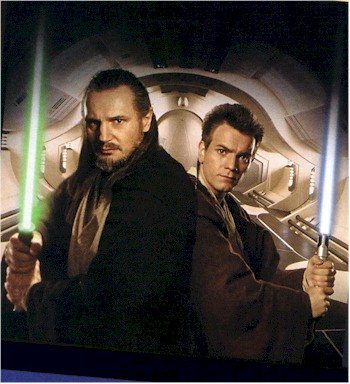

STAR WARS: EPISODE 1—THE

PHANTOM MENACE

**

Directed and written by George Lucas

With Liam Neeson, Ewan McGregor,

Natalie Portman, Jake Lloyd, Ian McDiarmid,

Pernilia August, Ahmed Best, Frank Oz,

Samuel L. Jackson, and Ray Park.

TREKKIES

0

Directed by Roger Nygard

The big question about the Star War series, and The Phantom Menace in particular, isn’t how much you like it but whether you love it. The issue is above all generational, and only secondarily a matter of aesthetic or ideological choices.

If you’re male and were born around 1989, the chances of you loving The Phantom Menace seem fairly high. If you’re male or female and were born around 1967, the chances of you loving it are probably almost as high. Read more

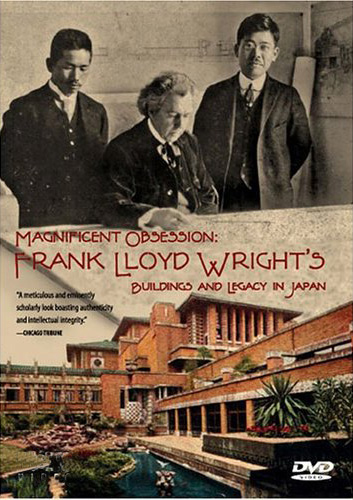

This originally appeared in the July 22, 2005 issue of the Chicago Reader; I’ve slightly extended it here, pictorially as well as verbally, on February 8, 2010. — J.R.

MAGNIFICENT OBSESSION: **

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT’S

BUILDINGS AND LEGACY

IN JAPAN

DIRECTED BY KAREN SEVERNS

AND KOICHI MORI

WRITTEN BY SEVERNS

NARRATED BY AZBY BROWN AND

DONALD RICHIE

It’s widely known that Japan had a profound influence on the work of Frank Lloyd Wright. But how many of us have the chance to discover that the reverse is also true? According to the commentary written by Chicago native Karen Severns for Magnificent Obsession: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Buildings and Legacy In Japan — a 128-minute American documentary (2004) she made with her Japanese husband Koichi Mori, which also exists in a Japanese version —- the effort to distinguish between emulations and imitations of Wright in Japanese architecture criticism is no small affair, and “At one point, there were 32 Wright-related terms in the [Japanese] architectural lexicon.”

One could posit a certain analogy between this oscillating cultural exchange and a process set in motion by some young, maverick French film critics in the 50s. Their eccentric enthusiasm for some Hollywood directors produced a new kind of French cinema and French film criticism, and this wound up influencing 60s Hollywood and American film criticism in turn. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 29, 1989). — J.R.

(

REMBRANDT LAUGHING

Directed and written by Jon Jost

With Jon A. English, Barbara Hammes, Jim Nisbet, Nathaniel Dorsky, Janet McKinley, Kate Dezina, and Jerry Barrish.

“The essence of Jean-Luc Godard’s La femme mariée,” John Bragin wrote in the mid-60s, “is the transmutation of the dramatic into the graphic.” While this formula doesn’t account for everything in Rembrandt Laughing, Jon Jost’s ninth feature, I think it provides a helpful clue to the overall direction taken by this masterful, elliptical account of a little over a year in the lives of a few friends in San Francisco.

For all his mastery and originality as a maverick independent, Jost has often alienated audiences with the harshness of his themes and the apparent distance from which he views his subjects and his characters. A 60s radical who spent over two years in federal prison for draft resistance, he has lived without a fixed address for most of his 26-year career as a filmmaker, and the alienation as well as the clarity stemming from his wanderlust has seeped into many of his fiction features. These have often centered on isolated individuals: a private detective in Angel City (1977), a drifter out of work in Last Chants for a Slow Dance (1977) [see two images below], a drug dealer in Chameleon (1978), a Vietnam vet in Bell Diamond (1987). Read more

From The Guardian (July 4, 2003). — J.R.

One of the most neglected major film-makers of the 20th century, Alexander Dovzhenko has never come close to receiving his due. This is in part a problem related to our categories and labels. His fervent, pantheistic, folkloric films develop more like lyric poems, moving from one stanza to the next, than like narratives, proceeding by way of paragraphs or chapters. The world they describe is one of Gogolesque horses that sing or reprimand their owners, noble cows, glistening meadows, wily Cossacks, dancing peasants, declamatory speeches by wild-eyed individuals, sunflowers in sunny close-ups alongside noble women with similarly open faces, vast reaches of empty sky over fields of waving wheat.

Dovzhenko’s vision is of a natural order that paradoxically seems both brutal and harmonious, primitive landscapes bursting with animal and vegetal life. One calls this poetry because it comprises a paean to sheer existence, singing about rather than relating or recounting what it sees. But cinema as it’s generally packaged is understood more in terms of prose narrative, as a string of events. In Dovzhenko’s world, the events often turn out to be the shots themselves.

Furthermore, most accounts we have of Dovzhenko’s work are found in discussions of Russian cinema, but the man wasn’t Russian. Read more

From The Guardian (May 30, 2003). –J.R.

For roughly two decades, my three favourite dramatic features have all been the work of the same man — and my favourite among these depends almost entirely on which one I’ve seen most recently. I came to know and love them in reverse order: first the incandescent and subtly erotic Gertrud (1964), discovered in my early 20s shortly after it premiered; then the gut-wrenching Ordet (1955), which I initially hated when I first saw it in my teens, misconstruing its climactic miracle as a tool of religious propaganda; and finally the voluptuous and mysterious Day of Wrath (1943), which I didn’t appreciate or understand until my 40s, when I finally saw it in a decent 35mm print.

Like all the greatest artists, Carl Theodor Dreyer demands to be taken as a figure whose work continues to grow and change, quite irrespective of the fact that he died in 1968 at the age of 79, with many of his most cherished projects (most notably, a film about Jesus) unrealised. Fresh insights about his life and career keep coming to light: not only through biographical research; the emergence of new prints (such as the remarkable 1981 rediscovery of the original 1927 version of The Passion of Joan of Arc in an Oslo mental hospital); but also through the uncanny fact that his films seem to grow more multilayered, ambiguous, and complex over time. Read more

This remains one of the most controversial reviews I ever published in the Chicago Reader (it ran in their September 17, 1993 issue) — occasioning many outcries, especially for my use of the term “drooling paisan” (although many others also quarreled with my point about apostrophes). No one, however, seemed to have had any quarrels with my treatment of Edith Wharton. — J.R.

THE AGE OF INNOCENCE

Directed by Martin Scorsese

Written by Jay Cocks and Scorsese

With Daniel Day-Lewis, Michelle Pfeiffer, Winona Ryder, Stuart Wilson, Miriam Margolyes, Geraldine Chaplin, Mary Beth Hurt, and Norman Lloyd.

Martin Scorsese clearly intends The Age of Innocence — his close adaptation of Edith Wharton’s 1920 novel about wealthy New York society in the 1870s — to earn him a bouquet of Oscars. But the high literary tone was somewhat blown for me by the opening title, immediately following a lush credits sequence of flower blossoms unfurling behind dainty fabric: “New York City, the 1870’s.” That superfluous apostrophe doesn’t exactly inspire confidence that Scorsese is the ideal interpreter of Edith Wharton.

Fortunately the movie improves after that, but never to the point that one can entirely forget that slip at the beginning. If the project winds up a noble failure, testifying throughout to Scorsese’s resourcefulness in plowing through an impossible mission — much better to my taste than Cape Fear, and considerably more likable (if less successful) than GoodFellas — it may be because the subject is diametrically opposed to what he usually does best as a filmmaker. Read more

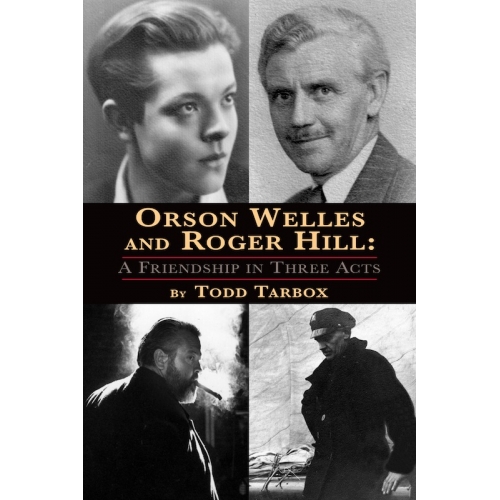

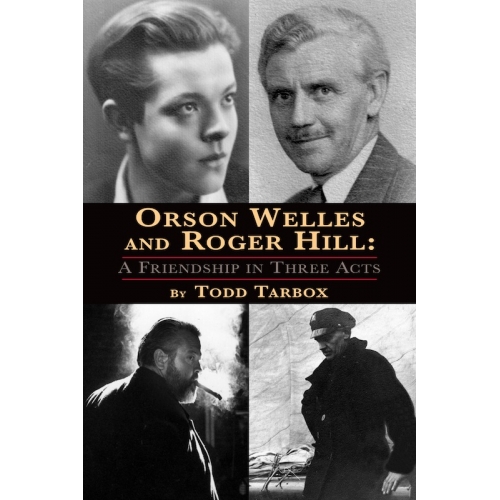

Almost seven years have passed since I quoted from the manuscript of this wonderful book in the Introduction to my own Discovering Orson Welles. At that point the subtitle of Todd Tarbox’s book was A Friendship in Four Acts, but if anything, the book has only grown since then, both physically and in terms of readability. In short, it’s been well worth the wait. (June 2014 footnote: For more details, including an excerpt from one of the Welles/Hill conversations, go to Todd Tarbox’s radio interview with Rick Kogan, here.) — J.R.

The major and longest-lasting close friendship of Orson Welles’s life was with one of his earliest role models — his teacher, advisor, and theatrical mentor at the Todd School who later became the school’s headmaster, Roger Hill. By editing and arranging many of their recorded conversations at the end of Welles’s life and career, Hill’s grandson, Todd Tarbox, has given us invaluable and candidly intimate glimpses into many of its stages, especially ones towards the beginning and end of that diverse and complicated saga. In the process, he also confounds and complicates the array of “weak” and flawed father figures that populate most of Welles’ films, all the way from Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersonsthrough The Trial, Chimes at Midnight, Don Quixote, and The Other Side of the Wind, with a bracing and ennobling alternative to that pattern, an unwavering relationship of mutual admiration and respect that was a clear source of strength to both of them. Read more

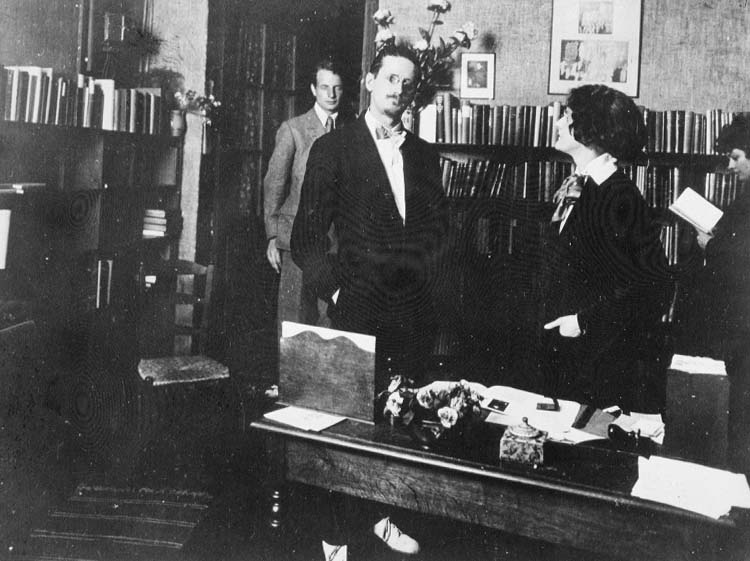

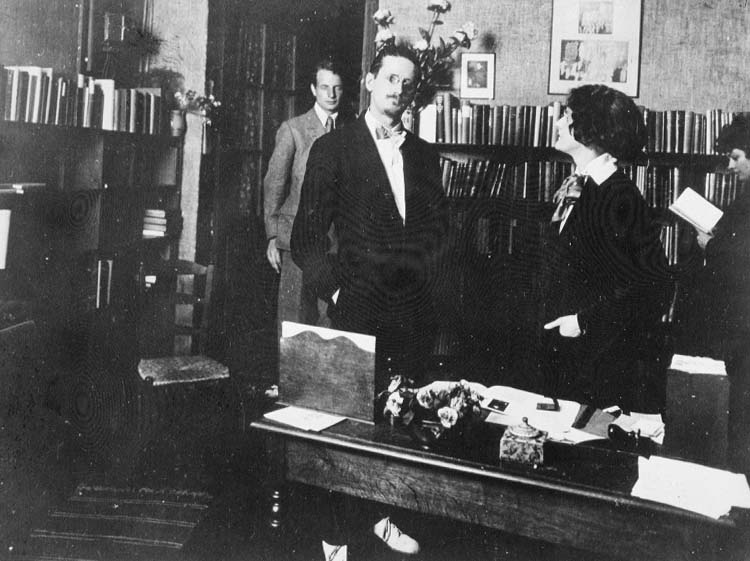

The year is 1921, the place Sylvia Beach’s celebrated Shakespeare and Company, publisher of the first edition of James Joyce’s Ulysses, Rue de l’Odéon, Paris. The figures, reading from left to right, are John Rodker, James Joyce, Sylvia Beach, and her younger sister Cyprian — the only one shown reading, to whom Sylvia dedicated the first edition of Ulysses.

In a review of Sylvia Beach’s letters by James Campbell in the March 19 issue of the Times Literary Supplement I learn that Cyprian “played `Belles Mirettes’ in the French silent film series Judex“. After some rummaging around, I discover that, in fact, `Miss Cyprien Giles’ played Gaby Belles Mirettes, a member of a criminal gang, in La Nouvelle Mission de Judex (1918), the only one of Louis Feuillade’s major crime serials I’ve never seen, and, according to the Internet Movie Database, appeared later in The Fortune Teller (1920), L’aiglonne (1921), and L’amie d’enfance (1922). And from Campbell’s review I learn that “she later lived with a somewhat better-known actress, Helen Jerome Eddy” (see photo below) — an actress who lived from 1897 to 1990 and who, according to the same IMDB, appeared in 130 films (not always credited) between 1915 and 1947, including The Bitter Tea of General Yen, Man’s Castle, and Bride of Frankenstein. Read more

This review from the August 1976 issue of Monthly Film Bulletin may represent my most exhaustive (and exhausting) attempt to extend the one-paragraph review format of that magazine almost to the point of infinity. — J.R.

Vampyr: Der Traum des Allan Gray (Vampyr: The Strange Adventure of David Gray)

Germany/France, 1932

Director: Carl Th. Dreyer

Cert — A. dist –– Cinegate. p.c –- Tobis-Klangfilm-France (Berlin-Paris)/Dreyer Filmproduktion (Paris). p –- Carl Th. Dreyer, Baron Nicolas de Gunsburg. asst. d –- Ralph Holm, Éliane Tayara, Preben Birck. sc -– Carl Th. Dreyer, Christen Jul. Inspired by the collection of stories In a Glass Darkly by Sheridan Le Fanu. ph -– Rudolph Maté, Louis Née. ed –- Carl Th. Dreyer. a.d –- Hermann Warm, Hans Bitman, Cesare Silvagni. m -– Wolfgang Zeller. English titles -– Herman G. Weinberg. sd -– Hans Bittman. Post-synchronisation -– Paul Falkenberg. l.p -– Julian West [Baron Nicolas de Gunzberg] (David Gray), Henriette Gérard (Marguerite Chopin), Sybille Schmitz (Léone), Renée Mandel (Gisèle), Maurice Schutz (Lord of the Manor), Jan Hieronimko (Doctor), Jane Mora (Nurse), Albert Bras and A. Babanini (Servants at the Manor). Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 8, 1992). — J.R.

JON JOST RETROSPECTIVE

Last week Jon Jost, a Chicago-born independent filmmaker, was having the first commercial run of his career — All the Vermeers in New York, his tenth feature, at the Music Box. Typically, he couldn’t be around for the event because he was busy shooting his 12th feature in Oregon.

The Music Box engagement launches a Jost retrospective that continues at Chicago Filmmakers on weekends for the remainder of this month. It’s the most exciting and important American retrospective to hit town since the Music Box’s John Cassavetes series last fall, though like that series it isn’t quite complete: only about half of Jost’s shorts — most made in the 60s and early 70s — are included, and two of his features, Bell Diamond (1985) and Sure Fire (1990), are omitted. (Sure Fire may open here in the fall if enough people go to see All the Vermeers in New York.) Still, it’s the most comprehensive show of Jost’s work that’s ever come to Chicago, and it offers a great chance to catch up with a singular career that has been more subterranean than most, even among American independents. Read more