A Critic’s Choice from the April 9, 1999 Chicago Reader. Seeing Luigi Zampa’s wonderful To Live in Peace (1947) yesterday, for the first time, at Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna, I discovered the same theme attached to an earlier and more “popular” war, expressed largely in comic and even farcical terms. — J.R.

Essential viewing. This documentary about a group of American and Vietnamese war veterans, many of them disabled, bicycling 1,200 miles from Hanoi to Ho Chi Minh City is many things at once — act of witness, account of a multicultural exchange, sports story, journalistic investigation, and mourning for the devastation of war. Ultimately it may be too many things to yield a cumulative effect, yet its scenes of former soldiers struggling with the meaning of the war are the most moving ones on the subject since Winter Soldier (a wartime agitprop film in which Vietnam veterans confessed their “war crimes”). The corporate sponsorship of the bicycle marathon adds many ironic layers, but the emotional encounters it permitted seem more important than anything else I’ve seen about our involvement in Vietnam. Coproduced by Chicago’s Kartemquin Films and directed by Jerry Blumenthal, Gordon Quinn, and Peter Gilbert (Hoop Dreams). Read more

From the Chicago Reader (August 1, 1993). — J.R.

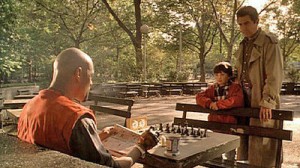

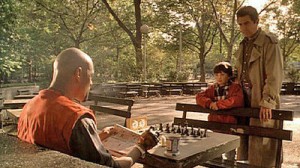

One of the craftiest and most satisfying pieces about gender politics to come along in ages (1993) — all the more crafty because audiences are encouraged to see it simply as a movie about a seven-year-old chess genius, based on Fred Waitzkin’s nonfiction book about his son Josh. Very well played (with Max Pomeranc especially good as Josh), shot (by Conrad Hall), and written and directed (by Steven Zaillian, who also scripted Schindler’s List), it gradually evolves into a kind of parable about how a gifted kid learns to choose his role models and choose what he needs from them. The part played by gender in all this is both subtle and complex, relating not only to chess strategy (e.g., when to bring your queen out) and the personality of Bobby Fischer, but also to the varying attitudes toward competition taken by his parents (Joe Mantegna and Joan Allen) and two teachers (Laurence Fishburne and Ben Kingsley). It makes for a good old-fashioned inspirational story, absorbing and pointed. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 6, 2002). — J.R.

Man Hunt

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Fritz Lang

Written by Dudley Nichols

With Walter Pidgeon, Joan Bennett, George Sanders, John Carradine, Roddy McDowall, Heather Thatcher, and Frederick Worlock.

A sparkling new 35-millimeter print of Fritz Lang’s 1941 Man Hunt is running at the Gene Siskel Film Center all this week, and I can recommend it without reservation. It’s not quite a masterpiece, but it’s considerably more entertaining than any new thrillers I’m aware of.

Man Hunt‘s status within Lang’s body of work is somewhat ambiguous and contested. Ten years ago one of France’s major film historians, Bernard Eisenschitz, wrote a 270-page book on the film in which he pored over many of the production materials as if they were holy writ. Yet Tom Gunning’s authoritative recent critical study, the 528-page The Films of Fritz Lang: Allegories of Vision and Modernity, scarcely deals with the film at all, apart from mentioning that it “would reward close analysis” and contending that it, like Lang’s three other anti-Nazi films — Hangmen Also Die! (1943), Ministry of Fear (1944), and Cloak and Dagger (1946) — is limited by its propagandistic qualities.

I only half agree with Gunning. Read more

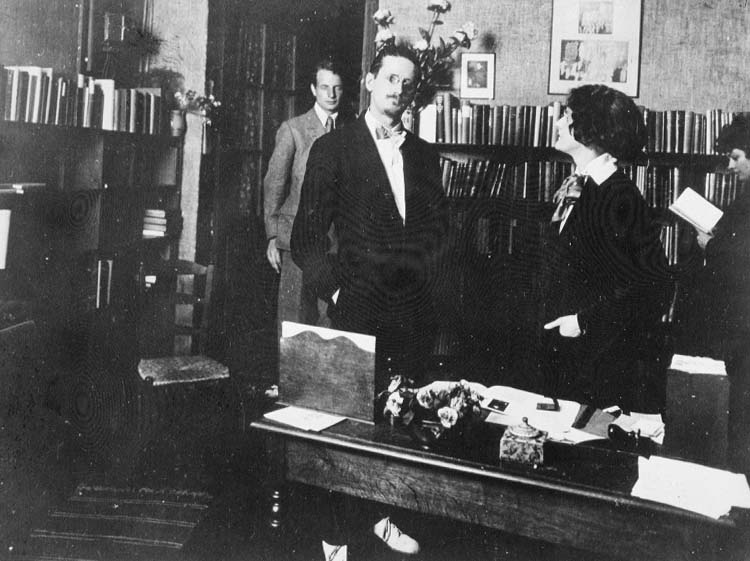

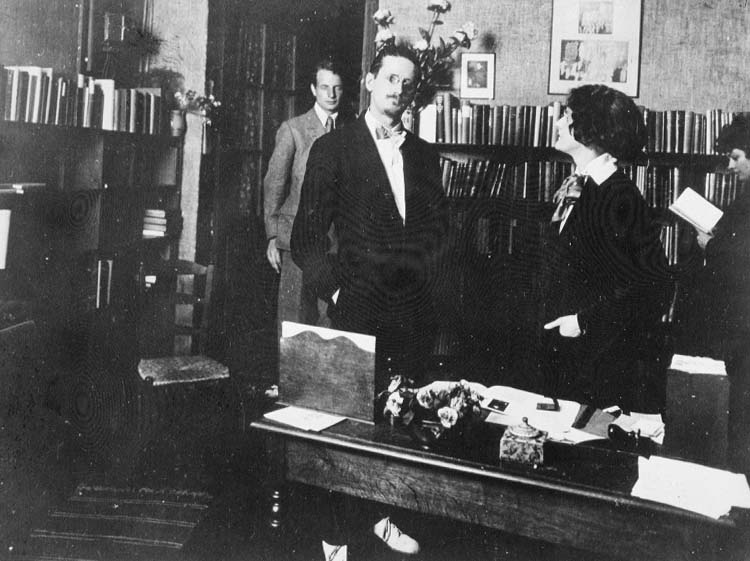

The year is 1921, the place Sylvia Beach’s celebrated Shakespeare and Company, publisher of the first edition of James Joyce’s Ulysses, Rue de l’Odéon, Paris. The figures, reading from left to right, are John Rodker, James Joyce, Sylvia Beach, and her younger sister Cyprian — the only one shown reading, to whom Sylvia dedicated the first edition of Ulysses.

In a review of Sylvia Beach’s letters by James Campbell in the March 19 issue of the Times Literary Supplement I learn that Cyprian “played `Belles Mirettes’ in the French silent film series Judex“. After some rummaging around, I discover that, in fact, `Miss Cyprien Giles’ played Gaby Belles Mirettes, a member of a criminal gang, in La Nouvelle Mission de Judex (1918), the only one of Louis Feuillade’s major crime serials I’ve never seen, and, according to the Internet Movie Database, appeared later in The Fortune Teller (1920), L’aiglonne (1921), and L’amie d’enfance (1922). And from Campbell’s review I learn that “she later lived with a somewhat better-known actress, Helen Jerome Eddy” (see photo below) — an actress who lived from 1897 to 1990 and who, according to the same IMDB, appeared in 130 films (not always credited) between 1915 and 1947, including The Bitter Tea of General Yen, Man’s Castle, and Bride of Frankenstein. Read more

This review from the August 1976 issue of Monthly Film Bulletin may represent my most exhaustive (and exhausting) attempt to extend the one-paragraph review format of that magazine almost to the point of infinity. — J.R.

Vampyr: Der Traum des Allan Gray (Vampyr: The Strange Adventure of David Gray)

Germany/France, 1932

Director: Carl Th. Dreyer

Cert — A. dist –– Cinegate. p.c –- Tobis-Klangfilm-France (Berlin-Paris)/Dreyer Filmproduktion (Paris). p –- Carl Th. Dreyer, Baron Nicolas de Gunsburg. asst. d –- Ralph Holm, Éliane Tayara, Preben Birck. sc -– Carl Th. Dreyer, Christen Jul. Inspired by the collection of stories In a Glass Darkly by Sheridan Le Fanu. ph -– Rudolph Maté, Louis Née. ed –- Carl Th. Dreyer. a.d –- Hermann Warm, Hans Bitman, Cesare Silvagni. m -– Wolfgang Zeller. English titles -– Herman G. Weinberg. sd -– Hans Bittman. Post-synchronisation -– Paul Falkenberg. l.p -– Julian West [Baron Nicolas de Gunzberg] (David Gray), Henriette Gérard (Marguerite Chopin), Sybille Schmitz (Léone), Renée Mandel (Gisèle), Maurice Schutz (Lord of the Manor), Jan Hieronimko (Doctor), Jane Mora (Nurse), Albert Bras and A. Babanini (Servants at the Manor). Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 8, 1992). — J.R.

JON JOST RETROSPECTIVE

Last week Jon Jost, a Chicago-born independent filmmaker, was having the first commercial run of his career — All the Vermeers in New York, his tenth feature, at the Music Box. Typically, he couldn’t be around for the event because he was busy shooting his 12th feature in Oregon.

The Music Box engagement launches a Jost retrospective that continues at Chicago Filmmakers on weekends for the remainder of this month. It’s the most exciting and important American retrospective to hit town since the Music Box’s John Cassavetes series last fall, though like that series it isn’t quite complete: only about half of Jost’s shorts — most made in the 60s and early 70s — are included, and two of his features, Bell Diamond (1985) and Sure Fire (1990), are omitted. (Sure Fire may open here in the fall if enough people go to see All the Vermeers in New York.) Still, it’s the most comprehensive show of Jost’s work that’s ever come to Chicago, and it offers a great chance to catch up with a singular career that has been more subterranean than most, even among American independents. Read more