This originally appeared in the July 22, 2005 issue of the Chicago Reader; I’ve slightly extended it here, pictorially as well as verbally, on February 8, 2010. — J.R.

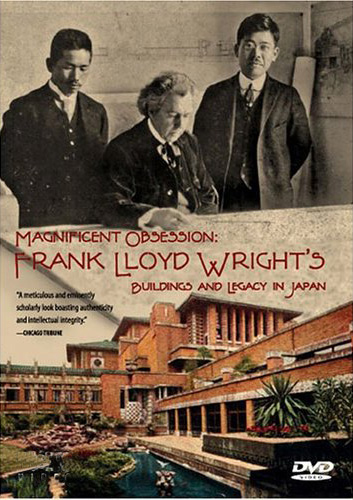

MAGNIFICENT OBSESSION: **

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT’S

BUILDINGS AND LEGACY

IN JAPAN

DIRECTED BY KAREN SEVERNS

AND KOICHI MORI

WRITTEN BY SEVERNS

NARRATED BY AZBY BROWN AND

DONALD RICHIE

It’s widely known that Japan had a profound influence on the work of Frank Lloyd Wright. But how many of us have the chance to discover that the reverse is also true? According to the commentary written by Chicago native Karen Severns for Magnificent Obsession: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Buildings and Legacy In Japan — a 128-minute American documentary (2004) she made with her Japanese husband Koichi Mori, which also exists in a Japanese version —- the effort to distinguish between emulations and imitations of Wright in Japanese architecture criticism is no small affair, and “At one point, there were 32 Wright-related terms in the [Japanese] architectural lexicon.”

One could posit a certain analogy between this oscillating cultural exchange and a process set in motion by some young, maverick French film critics in the 50s. Their eccentric enthusiasm for some Hollywood directors produced a new kind of French cinema and French film criticism, and this wound up influencing 60s Hollywood and American film criticism in turn. (It took prompting from the French before American as well as English critics were ready to take Alfred Hitchcock seriously as an artist.) Fashioning a chronology of the cultural exchanges between Wright and Japan is a worthy endeavor, but doing so in a way that can speak equally to the interests of American and Japanese viewers is far from simple. Part of the lesser- known story told here concerns Arata Endo, selected as Wright’s major assistant on the Imperial Hotel [see first photograph above and the next three photographs below] when he was 27, who eventually became the only person Wright ever allowed to share architectural credit with him (for at least two buildings — the progressive School of the Free Spirit for girls in Tokyo and for a summer villa in Ashiya). We also learn about Czech-born Antonin Raymond, a Wright apprentice who arrived from the states and then as he remained in the country for 43 years became a leading figure in Japanese modernism.

What we learn less about is the impact of Japanese art and architecture on Wright’s American buildings. Wright always readily acknowledged the influence of the former (particularly the “abstract geometrical shapes, vivid colors, and unusual perspectives” of Japanese woodblock prints) and soft-peddled or denied the influence of the latter — but then again he always showed reluctance in admitting to any direct architectural influences. (Speaking Wright’s own words in the narration is our premier American interpreter of Japanese culture, film in particular, Donald Richie.)

The visits of Wright to Japan chronicled in this film span only 17 years, starting with his very first trip abroad (in 1905, at age 37) and culminating with his work on Tokyo’s awesome Imperial. They weren’t exactly casual visits; in 1916, he sailed into Yokohama with a grand piano and a yellow convertible in tow, and in 1905 he brought back to the states enough prints, textiles, and ceramics to curate a show at Chicago’s Art Institute the following year — launching a kind of sideline in Japanese art that would become a major source of income over the next two decades. But the story of the two-way cultural traffic between him and that culture is so intricate that even a two-hour film can barely scratch the surface. And the surface that’s scratched here is mainly the view from there, not here, with the epic tale of the Imperial’s long-term construction taking pride of place. This huge hotel consolidated Wright’s international reputation not only because its innovative floating mud foundation enabled it to survive a 1922 earthquake that left 70% of Tokyo in rubble and three and a half million people homeless, but also because its scale makes it sound like a contemporary equivalent to the Pyramids: Wright had a hundred stonecutters at his disposal for incidental décor, designed even the china used in the restaurant, and at one point commanded a work force of a thousand laborers to bring it to completion. It was the first all-electric hotel in Asia and contained Japan’s first shopping arcade and first hotel laundry service. This film’s climactic photos of this now lost masterwork, each one mutating from black and white to color, is its aesthetic high point.

But the closest thing to an overall summation comes at the beginning: “Without Japan, there may have been no second golden age for Frank Lloyd Wright. Without Frank Lloyd Wright, Japan may have forsaken its ancient craft traditions and sacrificed its proud architectural past in the pursuit of modernization.” But since this documentary understandably privileges the Imperial, this could misleadingly prompt the conclusion that Wright’s greatest accomplishments in the U.S. were also his blockbusters, and I’m far from alone in rejecting this premise. Wright hated cities and many of his most famous urban designs —- including parts of the Imperial — reflect his animosity in their moves towards deurbanized environments. One of his late proposals for New York housing, voiced on Mike Wallace’s TV show during my early teens, was surrounding two mile-high buildings with countless acres of greenery. So I’m far from sympathetic when this film’s narration calls his uncharacteristically urban Guggenheim “the world’s most remarkable museum”. (My tentative counter-proposal for this epithet would be the Royal Palace Museum in Taipei, which arguably houses the most treasures, and does so in a way that’s arguably more respectful to the art works.)

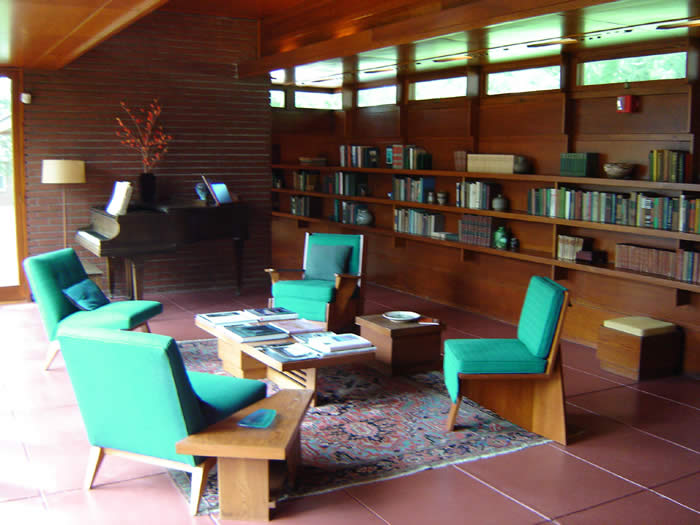

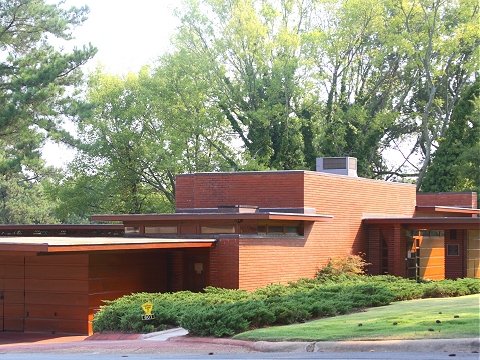

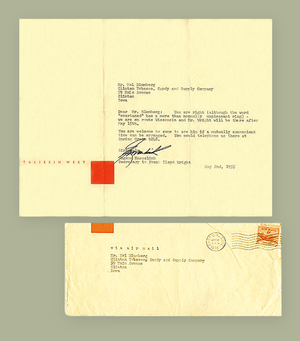

Certainly Wright served as a special kind of slanted mirror for Japan, meanwhile using that same slant to inform and refine his own work. Having had the privilege to grow up in a Wright house [see two photos above] — the only one in Alabama, designed for my parents in Florence in 1940, expanded by Wright after the family grew, and recently restored as a public museum —- I’ve defined some of this slant on my own terms as a snug economy of horizontally conceived domestic space, a heated floor following the dips and rises of the terrain, and a proximity and interaction between functional interiors and leafy exteriors that embraced the back yard [see second photo above] while turning its back on the street. After my mother converted a sloping patio lawn in the back of the new wing into a Japanese rock garden, its resemblance to the self-conscious and suburban obstacle course in Tati’s Mon oncle spoiled it for me as a site of contemplation. But everything else in the house that still looks and feels Japanese, from the Cinemascope sweep of the front [see third and fourth photo above] to the sliding door that led to the new wing, fosters a keen sense of cozy proximity and continuity.

It would have been interesting if Severns and Mori had explored some of the other ramifications of Wright’s love of Japan on his American identity, and not only as an architect. My parents often recalled the controversial newsletters sent from Wright’s Taliesin during World War 2 that persisted in defending Japan in spite of everything, and it would be intriguing to hear today what some of those arguments consisted of. But in telling the Japanese side of the story, this couple has at least clarified an important if lesser-known chapter in the architect’s work.

July 29 (Letters, Chicago Reader):

In my review of Karen Severns and Koichi Mori’s Magnificent Obsession: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Buildings and Legacy in Japan [July 22] I said that Arata Endo was the only person with whom Wright ever agreed to share architectural credit, information I got from the documentary. But my brother Alvin Rosenbaum, author of the 1993 book Usonia: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Design for America, tells me that Wright shared credit with at least one other person, Aaron Green, “on their joint San Francisco office,” adding that “their major collaboration, the Marin County Courthouse, was finished after Wright’s death.”

Jonathan Rosenbaum