From the Chicago Reader (July 1, 1994). — J.R.

A first feature by American independent writer-director David O. Russell, this traps its hero, a premed college freshman, in his family’s suburban home for the summer. Forced to give up an internship to take care of mother (laid up with a broken leg) while his philandering father, a traveling video salesman, is out on the road, the not very likable hero finds himself in one tragicomic mishap after another involving his father’s convoluted instructions, care of the family dog, making out with a high school senior, and a growing sexual involvement with his desperate mother. Despite a certain originality, the movie isn’t really a success, not only because the plot bites off more than it can chew (the film doesn’t conclude; it simply stops), but also because, like its hero, it has some trouble distinguishing between petty irritations and cataclysmic traumas. But at least the performances are fresh and fairly nuanced. With Jeremy Davies, Elizabeth Newitt, Benjamin Hendrikson, Alberta Watson, Carla Gallo, and Richard Husson (1994). (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the August 15, 2003 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

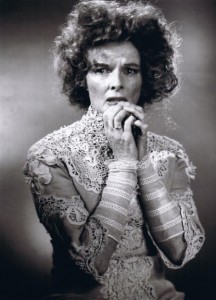

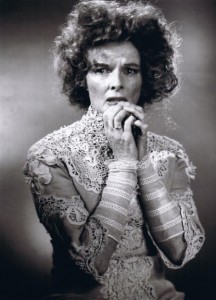

Eugene O’Neill’s greatest play — written in 1940, but published only posthumously, in 1956 — is a frankly autobiographical look at his own doomed family, set in 1912, when he was in his early 20s. Sidney Lumet rightly retained the entire text for this 1962 black-and-white feature, which runs for 174 minutes. It’s as close to a definitive version as we’re likely to get, and it includes what is probably Katharine Hepburn’s greatest noncomic performance. The other three actors — Ralph Richardson as the father, Jason Robards Jr. as the older son, and Dean Stockwell as the younger son (O’Neill’s self-portrait) — keep pace with her every step of the way. (JR)

Read more

Read more

Written for the catalogue of Il Cinema Ritrovato, June 24 through July 4, 2015. — J.R.

THE MAN FROM LARAMIE

USA, 1955

T. it.: L’ Uomo di Laramie. Sog.; Thomas T. Flynn. Scen.: Philip Yordan, Frank Burt. F. (CinemaScope): Charles Lang. M.: William Lyon. Mus.: George Duning, Lester Lee. Int.: James Stewart (Will Lockhart), Arthur Kennedy (Vic Hansbro), Donald Crisp (Alec Waggoman), Cathy O’Donnell (Barbara Waggoman), Alex Nicol (Dave Waggoman), Aline MacMahon (Kate Canady)., Wallace Ford. Prod.: William Goetz Productions.

“Anthony Mann brought a touch of Oedipus Rex to almost everything he did—he was fascinated by families exploding from the inside—but in this 1955 western it’s more than a touch: he’s clearly aiming for classical resonance. Yet the film is never pretentious, perhaps because Mann is able to create characters complex enough to support the grand emotions, and because the landscape—animistic, enveloping—becomes mythic in his wide-screen framing. It’s one of Mann’s cleanest, clearest films, constructing an elaborate but ultimately lucid network of character relationships, all of them perverse. With James Stewart, Arthur Kennedy, and Donald Crisp. 104 min.” (Dave Kehr in the Chicago Reader)

This is the eight and last of Anthony Mann’s features starring James Stewart, made over a mere six years (1950-1955)—a fascinating body of work that, like Alfred Hitchcock’s uses of Stewart over roughly the same period (in Rope, Rear Window, and Vertigo) as well Cecil B. Read more

The following was commissioned by and written for Asia’s 100 Films, a volume edited for the 20th Busan International Film Festival (1-10 October 2015). — J.R.

A Brighter Summer Day was inspired by a true incident, a touchstone from Yang’s youth: the killing of a 14-year-old girl by a male high school student in Taipei on June 15, 1961. Yang frames the film with recitations over the radio of the names of students graduating from the same school in 1960 and ’61. The title comes from the lyrics of the Elvis Presley song “Are You Lonesome Tonight?”, phonetically transcribed by the hero’s sister so that a younger friend, Cat, can learn to sing them.

This song is only one of many cherished artifacts belonging to the film’s characters that come from somewhere else. A samurai sword found by the hero, Si’r, in his family’s Japanese house becomes the murder weapon, and a tape recorder left by the American army in the 50s records Cat’s version of the Elvis song. An old radio that for most of the picture doesn’t work eventually broadcasts the list of graduating students. And a flashlight Si’r steals in the first extended scene from a film studio next to the school, where he periodically hides in the rafters to watch movies being shot, makes a fascinating progress through the film. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (August 1, 2001). — J.R.

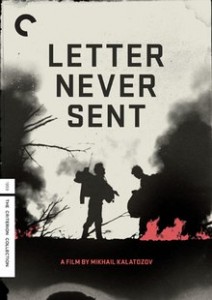

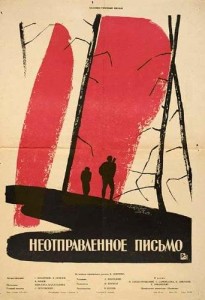

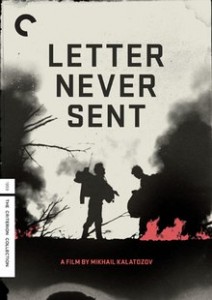

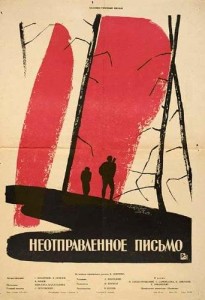

Two years after his internationally famous The Cranes Are Flying and five years before his internationally scorned I Am Cuba, Mikhail Kalatozov directed this strange 1959 adventure story about four geologists (three men and one woman) hunting for diamonds in Siberia. The title letter is being written by the narrator to his wife in Moscow, and while the explorers eventually find their treasure, they have to endure forest fires and snowstorms as they struggle back toward civilization. Though shot on location and reportedly based on a true story, the film is distanced considerably from realism, at least in any conventional sense, by its exciting and volatile camera style and its metaphysical atmosphere (sparked in particular by one line of dialogue, Nature is taking revenge); they’re less delirious than in I Am Cuba but sufficiently ravishing to have brought charges of formalism against the filmmakers. Pictorially, the double exposures and silhouette effects recall some of the glories of silent cinema. in Russian with subtitles. 98 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

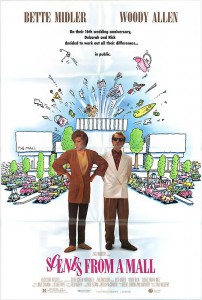

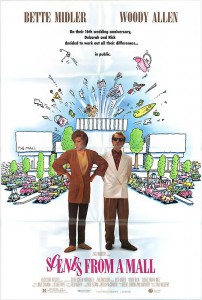

From the Chicago Reader (February 1, 1991). — J.R.

A middle-aged couple (Woody Allen and Bette Midler) in southern California celebrating their 15th anniversary go to a shopping mall, and they proceed to decompose and recompose their relationship on the basis of various revelations. Although this only runs for about 90 minutes, it’s the emptiest and most long-winded movie Paul Mazursky (working here with his frequent cowriter Roger L. Simon) has ever made, a disappointingly steep descent after his Enemies, a Love Story. The characters never come to life, and restricting almost all of the action to a gigantic mall only makes the narrowness and boredom of the movie more obvious. Mazursky has returned with a vengeance to his special universe where the upper middle class is the only thing that exists, and this time he has absolutely nothing to say about it. (JR)

Read more

Read more

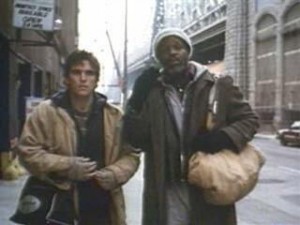

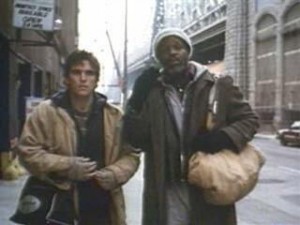

From the Chicago Reader (January 7, 1994). — J.R.

It would appear that many of my colleagues have been trashing this powerful and moving look at friendship among the homeless in New York — directed by Tim Hunter (River’s Edge) from a script by Lyle Kessler (Orphans) and starring Danny Glover and Matt Dillon at their rare best — simply because of its subject matter and authenticity; apparently, contemporary man-made tragedies are inappropriate topics for the big screen, unlike ghosts, dinosaurs, mythical serial killers, and former holocausts. But if epic grandeur is what you’re looking for, this movie gives you glimpses of the Fort Washington Armory, which currently shelters 700 people nightly, that recall the famous shot of the Confederate wounded in Gone With the Wind, and if noir finality is your meat, this movie tells you things about New York’s potter’s field that easily might have found their way into Pickup on South Street. This isn’t a perfect movie, and it may occasionally err on the side of Dickensian sentiment, but I it has so much to say about the world we live in and says it with such grace, wit, and raw feeling that I recommend it without qualification. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 1, 2001). — J.R.

As a rule, my favorite Woody Allen films are those select few that (a) warmly acknowledge Allen’s working-class roots, (b) steer clear of European influences, and (c) seek mainly to entertain. Manhattan Murder Mystery did the latter two wonderfully, and Broadway Danny Rose did all three, as does this charming throwaway, set in 1940. One thing I especially like about it, apart from the flavorsome 40s decor in color, is that it’s silly in much the same way that many small 40s comedies were. Allen is an insurance investigator and Helen Hunt an efficiency expert working for the same company; they hate each other with a passion — until they’re hypnotized during a nightclub act into not only loving each other madly but also stealing jewels whenever posthypnotic suggestions are delivered. Others in the cast include Dan Aykroyd, Elizabeth Berkley, Brian Markinson, Wallace Shawn, David Ogden Stiers, and Charlize Theron. 104 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 17, 1997). — J.R.

Writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson’s second feature (after Hard Eight) is a two-and-a-half-hour epic about one corner of the LA porn industry during the 70s and 80s — a seemingly limited subject that becomes the basis for a suggestive and highly energetic fresco. The sweeping first hour positively leaps with swagger and euphoria as an Orange County busboy (Mark Wahlberg) is plucked from obscurity by a patriarchal pornmeister (Burt Reynolds at his near best) to become a sex star. Alas, this being the American cinema, tons of gratuitous retribution eventually come crashing down on practically everybody in mechanical crosscutting patterns, and because Anderson has bitten off more than he can possibly chew, a lot of his minor characters are never developed properly. Moreover, just as Hard Eight at times slavishly depended on Jean-Pierre Melville’s Bob le flambeur, Anderson’s idea of a smart move here is to “outdo” Tarantino (in a fabulous late sequence with Alfred Molina) and to plagiarize a sequence from Raging Bull that itself quotes from On the Waterfront, rather than come up with something original. But notwithstanding its occasional grotesque nods to postmodernist convention, this is highly entertaining Hollywood filmmaking, full of spark and vigor. Read more

These questions were sent by Maya Bogovejic on April 17 for her Eastern European, online film journal Camera Lucida. — J.R.

1. How has the Coronavirus pandemic affected your creative work/project/film (in its different phases)?

I’m troubled as well as delighted by the fact that the pandemic has been good for my web site, the center of my creative activities, insofar as more people currently visit this site every day. But what does it mean to say that anything that’s bad for humanity can be good for something else? Surely this must be the ultimate logic of capitalism — the same logic as saying that Donald Trump is “good” for “television” (meaning, I suppose, the few billionaires who control television) but “bad” for “America” (meaning far more than a few of the people living in the U.S.)

All this means that the Coronavirus pandemic is forcing to the surface contradictions, inequalities, and injustices that have been around for some time but were much easier to ignore or rationalize when the state of things was simply “business as usual”.

2. How damaging (long-lasting…) will the consequences be for film art, film festivals, cinemas, coproductions, film centres, various film events…?

Read more

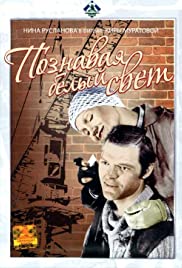

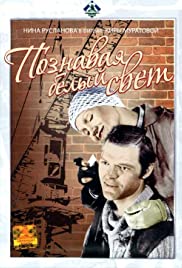

From the May 27, 2005 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Kira Muratova’s flaky 1978 feature, said to be her favorite, also goes by the title Understanding Life, but as often happens with her movies, appreciation ultimately triumphs over understanding. A loosely plotted comedy about a romantic triangle, set in and around a rural wasteland, it alternates between silence and sound, stopping and starting, with the cheekiness of 60s Godard. The relative chaos of the construction-site location, like the ones in Alexander Dovzhenko’s Ivan and Aerograd, is what Muratova seems to like most about this. As usual with her movies, the actors — including regulars Nina Ruslanova and Sergei Popov — are wonderful. In Russian with subtitles. 80 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the June 1, 1991 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

For his filmmaking debut, writer, actor, and stage director Simon Callow has taken on the celebrated novella of Carson McCullers, making some use of Edward Albee’s stage adaptation but paring away much of its dialogue, including the use of an onstage narrator. The grotesque plot, set in a southern mill town during the Depression, concerns a circle of unrequited love: an eccentric bootlegger and folk doctor (Vanessa Redgrave) dotes on a hunchbacked dwarf (Cork Hubbert) who in turn loves an embittered convict (Keith Carradine), once the bootlegger’s husband. The pain of all this builds to an excruciating and violent fist fight between the bootlegger and the convict, witnessed by the entire town. The three leads are superb, and Rod Steiger and Austin Pendleton are fine in small roles. If Callow accords his stars a few too many close-ups, he still does a creditable job of trying to get us to believe in a tale that is difficult to imagine without the fragile weave of McCullers’s prose (Callow evidently sees it as a fairy tale with elements of magical realism). His stage background helps as well as hinders: one never believes in the town as anything but a set populated by actors, but the concentration of his direction certainly solicits the utmost from his cast. Read more

My favorite Fassbinder feature (1973; not shown in the U.S. for years because of problems involving the rights to the Cornell Woolrich source novel) is a horrific black comedy — a devastating view of bourgeois marriage rendered in a delirious baroque style. Vacationing in Rome, a virgin librarian in her 30s (Margit Carstensen) meets a macho architect (Peeping Tom‘s Karlheinz Bohm) and winds up marrying him. It’s a match made in heaven between a masochist and a sadist, with the husband’s contempt and absurdly escalating demands received by the fragile heroine as her proper due. Suspenseful and scary, excruciating and indigestible, this is provocation with genuine bite — though the manner often suggests a parody of a 50s Douglas Sirk melodrama. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 1, 2000). — J.R.

It isn’t surprising that John C. Richards and James Flamberg won the prize for best screenplay at the 2000 Cannes film festival; this offbeat and unpredictable comedy-thriller throws so many curveballs, one right after another, that I doubt I’ve had more fun at an American movie this year. You should know as little in advance about the plot as possible, so let’s just say that the title heroine (Renee Zellweger), a poorly treated housewife in a small town in Kansas who’s addicted to a daytime soap and smitten with one of its main characters (Greg Kinnear), drives out west to find him, with a couple of bickering hit men on her tail. The latter are played by Morgan Freeman and Chris Rock — who may be the most exciting tragicomic duo to come along since Martin and Lewis and at the very least deserve a sitcom or comic strip detailing their further exploits. There’s a lot going on in this movie about fantasy fulfillment and folie a deux in general, and one of the most remarkable things about it is that it was directed by Neil LaBute, the writer-director of the highly misanthropic In the Company of Men and Your Friends & Neighbors; this starts out with a similarly nasty edge and then turns warmer, funnier, and perhaps even wiser by the minute. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 1, 1991). — J.R.

David Mamet shares with Ernest Hemingway a mannerist style of macho dialogue made up of short sentences and repeated phrases that lends itself to self-parody as well as parody. In this second step down the ladder from the promise of his first picture (House of Games), he seems to be approximating Hemingway in his mawkish For Whom the Bell Tolls period. Joe Mantegna plays an alienated cop who implausibly discovers his Jewish roots through a couple of cases he’s assigned to, and finds himself manipulated as much by Jewish terrorists as by his superiors on the police force. Despite the occasional snap and crackle of Mamet-talk at its most surreal (“They couldn’t find Joe Louis in a bowl of rice”), the movie is just plain silly when it isn’t merely unbelievable (the usually astute Mantegna, alas, never once springs to life), with a good many unsuspenseful suspense sequences and apolitical political ruminations. W.H. Macy, Natalija Nogulich, Ving Rhames, Rebecca Pidgeon, and Vincent Guastaferro are among the costars (1991). (JR) Read more