This review, originally published in August 3, 1990 Chicago Reader, was one of my first sustained efforts to write about the employment of jazz in movies. The movie isn’t as good or as entertaining as Lee’s latest messy Brechtian musical, Chiraq, although the latter film suggests once again that he still doesn’t have a clear sense of how to use music. — J.R.

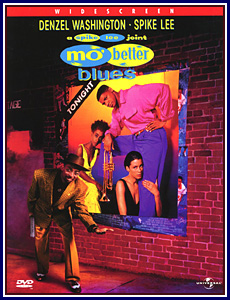

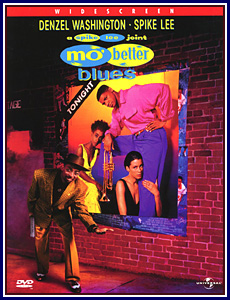

MO’ BETTER BLUES ** (Worth seeing)

Directed and written by Spike Lee

With Denzel Washington, Lee, Wesley Snipes, Giancarlo Esposito, Robin Harris, Joie Lee, Cynda Williams, Bill Nunn, Dick Anthony Williams, and John Turturro.

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

First the good news: strictly as an exercise de style, Spike Lee’s fourth joint is in certain respects the liveliest and jazziest piece of filmmaking he’s turned out yet. From the arty close-ups behind the opening credits of — and liquid pans past, and dissolves between –- trumpet, lips, and lovers’ grasping hands in blue, yellow, amber, and green to the matching semicircular crane shots that frame the story, this is a movie cooking with ideas about filmmaking. Bringing back a good many of the featured players in Do the Right Thing, and introducing to the Spike Lee stable the highly talented Denzel Washington, Cynda Williams, Wesley Snipes, and Dick Anthony Williams (among others), it’s a movie bursting with personality and actorly energy as well. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 1, 1990). — J.R.

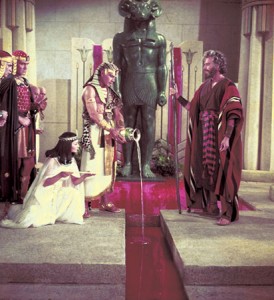

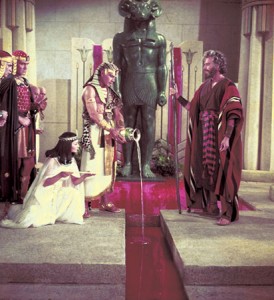

With a running time of nearly four hours, Cecil B. De Mille’s last feature and most extravagant blockbuster is full of the absurdities and vulgarities one expects, but it isn’t boring for a minute. Although it’s inferior in some respects to De Mille’s 1923 picture of the same title (which used the story of Moses as an extended prologue to a contemporary tale) and some of the special effects look less plausible now than they did in 1956, the color is ravishing, and De Mille’s form of showmanship, which includes a personal introduction and his own narration, never falters. Simultaneously ludicrous and splendid, this is an epic driven by the sort of personal conviction one almost never finds in more recent Hollywood monoliths. With Charlton Heston, Yul Brynner, Anne Baxter, Edward G. Robinson, Yvonne De Carlo, Debra Paget, John Derek, Cedric Hardwicke, H.B. Warner, Judith Anderson, Vincent Price, John Carradine, and many other familiar faces, including Woody Strode as the king of Ethiopia. 220 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 1, 1989). This lovely and sexy film is available on Twilight Time, with lots of extras (including deleted scenes and two separate audio commentaries). — J.R.

Real-life brothers Jeff and Beau Bridges play Jack and Frank Baker, a second-rate cocktail-lounge piano duo with staying power who hire sexy vocalist Susie Diamond (Michelle Pfeiffer) to strengthen their act, in the impressive 1989 directorial debut of screenwriter Steve Kloves (Racing With the Moon), who also wrote the script. Frank is the square brother who handles the business; he’s married, with kids, and not very musically inspired. Jack is remote, relatively irresponsible, and gifted; he plays jazz in his spare time and sounds like a leaner version of Bill Evans (his piano solos are dubbed, for the most part expertly, by Dave Grusin, the film’s music director). Susie is a former call girl who brings some soul to the group, as well as some problems when she and Jack develop a mutual attraction. This pared-away comedy-drama, which concentrates exclusively on the three characters, has plenty of old-fashioned virtues: deft acting, a nice sense of scale that makes the drama agreeably life-size, a good use of Seattle locations, fluid camera work (by Michael Ballhaus), a kind of burnished romanticism about the music, and a genuine feeling for the characters and their various means of coping. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 1, 1989). — J.R.

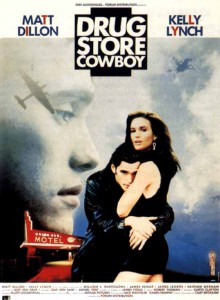

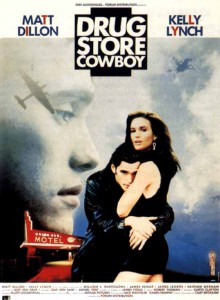

This amiable, no-nonsense account of a quartet of Portland, Oregon, junkies in 1971 fully lives up to the promise of Mala Noche, director Gus Van Sant’s previous feature. Adapted by Van Sant and Daniel Yost from an unpublished autobiographical novel by James Fogle, this 1989 feature has the kind of stylistic conviction that immediately wins one over; it conveys something of a junkie’s inner life with its editing rhythms, unorthodox use of sudden close-ups, hallucinatory passages, and Matt Dillon’s offscreen narration, and it documents the outer necessities of the lifestyle (including many drugstore robberies and changes of address). The characters are all quirky and life-size (the Dillon character’s superstitiousness is one of the principal motors of the plot, and the story’s outcome doesn’t prove him wrong), and like Bill Forsyth’s handling of the burglaries in Breaking In, Van Sant’s treatment of drugs is refreshingly free of either moralizing or romanticizing. It’s one indication of his ease and assurance that he successfully integrates the persona of William S. Burroughs into a fiction film: all the actors are used expertly, but it’s Burroughs, cropping up near the end, who articulates the film’s sociopolitical moral in a contemporary context. Read more

From the March 1, 1988 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Based on a play that constitutes part two of Neil Simon’s autobiographical trilogy, concerned with the experiences of the hero (Matthew Broderick) at boot camp in Biloxi, Mississippi, in 1943, this is an engaging, well-crafted comedy that receives very able direction from Mike Nichols. The period decor and details are nicely handled (apart from the silly decision to adapt clips from Buck Privates and Movietone News to the ‘Scope format, yielding an unnecessary anachronism), and while most of the characters are fairly standard types — sadistic drill sergeant (Christopher Walken), Jewish intellectual (Corey Parker), Polish lout (Matt Mulhern), raunchy prostitute (Park Overall), sophisticated girlfriend (Penelope Ann Miller) — the actors give them their best shot, including the somewhat miscast Walken. The nostalgic visual style of the film, successfully modeled on Norman Rockwell by production designer Paul Sylbert and cinematographer Bill Butler, is especially fetching, and the somewhat Woody Allen-ish offscreen narration shows Simon at his best. Perhaps this movie isn’t as wise or as profound as Simon wants it to be, but it is certainly a cut above sitcom complacency, and packed with wit and charm (1988). (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 8, 1996). — J.R.

One swell reason for seeing this fresh Americanized remake of La cage aux folles — the 1978 French farce about a middle-aged gay couple — written by Elaine May for her old improv partner, producer-director Mike Nichols, and costarring Robin Williams and Nathan Lane as the couple — is its hilarious depiction of Pat Buchanan as played by Gene Hackman, which implies, among other things, that only a drag queen could adequately fulfill Buchanan’s dream of ideal womanhood. More specifically, the son (Dan Futterman) of the proprietor (Williams) of a Florida nightclub with a drag show called “The Birdcage” becomes engaged to the daughter (Calista Flockhart) of an ultraconservative senator (Hackman) who wants to visit his future in-laws, leading to frantic preparations for a dinner party at which the proprietor’s drag-queen partner winds up playing the boy’s mother. (Hackman’s wife, incidentally, is played by Dianne Wiest.) This isn’t the supreme masterpiece it might have been, but Nichols’s direction is very polished and some of the lines and details are awfully funny.

— Jonathan Rosenbaum

Read more

Read more

From the Los Angeles Times’ Calendar, June 14, 1987. For readers who might wonder how I could have ever gotten such an assignment, I should point out that in this period, the Los Angeles Times was running anti-Ishtar articles virtually every day over several weeks, so I assume that my contrary position must have had some interest for them strictly as a novelty. This piece is reprinted in my most recent collection, Cinematic Encounters 2: Portraits and Polemics (2019). — J.R.

In all of Elaine May’s films, one encounters a will to power, a witty genius for subversion and caricature, and a dark, corrosive vision that recalls the example of Eric von Stroheim. The legendary Austrian-born director who started out, like May, as an aggressive actor (“The Man You Love to Hate”), Stroheim the film maker was known throughoutthe ’20s for his intransigence and extravagance — what one studio head termed his “footage fetish’.

The thematic and stylistic parallels between May and Stroheim are equally striking. Broadly speaking, “A New Leaf” is her “Blind Husbands” — a bold first film about ferocious, cynical flirtation, with the writer-director in the lead part. The Miami of “The Heartbreak Kid matches the Monte Carlo of “Foolish Wives”; the squalor and hysteria of “Mikey and Nicky” hark back to “Greed.” Read more

From the Chicago Reader (December 3, 2004). — J.R.

For all his formidable gifts as a performer, Mike Nichols is celebrated mainly as a film director who delivers the goods — which means something only if the goods are worth delivering. Here he’s applied himself to Patrick Marber’s play about two men (Jude Law and Clive Owen) and two women (Julia Roberts and Natalie Portman) seducing, betraying, and punishing one another in various combinations. (The women never get it on, but in the film’s funniest sequence Law flirts with Owen while posing as Roberts in a chat room.) As in Nichols’s previous chamber works of romantic and sexual flagellation (Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Carnal Knowledge), the actors are brilliant, the dialogue extremely clever, and the direction assured. But by the end I couldn’t have cared less about any of the characters (2004). R, 98 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

A program note for the 1997 San Francisco International Film Festival. — J.R.

In this intense drama of courage and humanity in the face of the brutality of slavery, a plantation slave named Nightjohn (Carl Lumblv) defies the law by teaching another slave, a l2-year-old girl named Sammy (Allison Jones), how to read and write. The only other slave on the plantation who even knows the alphabet had a thumb and forefinger chopped off as punishment. Working with a theme akin to that of Ray Bradbury’s novel (and François Truffaut’s film) Fahrenheit 451 — though it’s given a substantially different edge by being set in the past rather than the future — Nightjohn views illiteracy as a central adjunct of slavery. The film isn’t merely a history lesson about people who lived some 165 years ago but a story with immediate relevance. Part of what’s so wonderful about it is its use of fairy-tale feeling to focus on real-life issues, not to evade or obfuscate them. Nightjohn’s ambience is placed at the service of myth — myth that embodies a lucid understanding of both slavery and literacy. Sammy and Nightjohn may sometimes come across as superhuman, but the world they inhabit and seek to change is in no sense fanciful. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 1, 1991). Twilight Time’s Blu-Ray of this film has a lot of interesting material about the changes made by Truffaut to Bernard Herrmann’s score. — J.R.

Despite the dedication of this 1967 film to Hitchcock and the use of his most distinguished collaborator, composer Bernard Herrmann, Francois Truffaut’s first Cornell Woolrich adaptation — the second was Mississippi Mermaid — is most memorable for lyrical moods and poetic flights of fancy that don’t seem especially Hitchcockian. Jeanne Moreau stalks gracefully through the film, wooing and dispatching a series of men like an avenging angel whose motivating obsession is spelled out only gradually; among her prey are Claude Rich, Jean-Claude Brialy, Michel Bouquet, Michel Lonsdale, and Charles Denner. Basically an exercice de style, and a good one at that. In French with subtitles. 107 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

This review originally appeared in the March 28, 1997 issue of the Chicago Reader.-— J.R.

The Graduate **

Directed by Mike NicholsWritten by Buck Henry and Calder WillinghamWith Anne Bancroft, Dustin Hoffman, Katherine Ross,William Daniels, MurrayHamilton, Elizabeth Wilson,and Brian Avery.

If I feel myself as the producer of my life, then I am unhappy. So I would rather be a spectator of my life. I would rather change my life this way since I cannot change it in society. So at night I see films that are different from my experiences during the day. Thus there is a strict separation between experience and the cinema. That is the obstacle for our films. For we are people of the 60s, and we do not believe in the opposition between experience and fiction. –- Alexander Kluge, 1988

The Graduate opened in December 1967, the same month the first successful human heart transplant was performed. It was a few weeks after the premiere of Bonnie and Clyde and about three months before the launching of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Among the albums that came out the same year were the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, the Rolling Stones’ Their Satanic Majesties Request, and the Mothers of Invention’s Absolutely Free. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 1, 1994). — J.R.

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger transfer the plot of Johann Strauss’s opera Die Fledermaus to postwar Vienna for a 1955 musical filmed in Technicolor and ‘Scope. Not one of their best movies (cf The Red Shoes and A Matter of Life and Death), but it’s certainly an engaging mannerist oddity that calls to mind such contemporary cross-references in delirium as Frank Tashlin and Vincente Minnelli, and the cast — Anton Walbrook, Michael Redgrave, Anthony Quayle, Mel Ferrer, Dennis Price, and Ludmilla Tcherina — is occasionally as enterprising as the candy-box decor. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the January 1, 1995 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

In the first of his independent features as producer-director (1953) Otto Preminger adapts his most successful stage production, a light romantic comedy by F. Hugh Herbert that ran for over 900 performances. Released without production code approval and condemned by the Legion of Decency for its use of such taboo phrases as virgin, seduce, and pregnant, none of which bothered anyone in the stage run, it’s regarded today mainly as a curio. Yet for all the movie’s staginess and datedness, it’s a more personal and ambiguous work than it initially appears to be. Architect William Holden ogles and picks up professional virgin Maggie McNamara at the Empire State Building and brings her back to his apartment, where his next-door neighbors — his former girlfriend (Dawn Addams) and her playboy father (David Niven) — quickly involve this potential couple in various intrigues. A certain prurient (as well as analytical) curiosity in Preminger’s distanced and mobile camera style makes McNamara seem slightly corrupt and Holden and Niven slightly innocent, despite all appearances to the contrary, and the sour aftertaste to this frothy material is an important part of what keeps the picture interesting. Read more

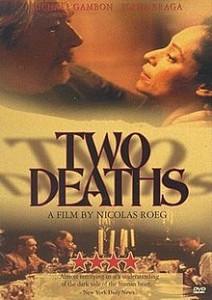

From the October 1, 1996 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

I don’t know anything about the novel this Nicolas Roeg made-for-BBC film is drawn from — Stephen Dobyns’s The Two Deaths of Senora Puccini, adapted by Roeg’s longtime collaborator Allan Scott — but its mixture of metaphysical fireside tale and kinky guilt tripping reminds me of Graham Greene’s Doctor Fischer of Geneva. During a bloody 1989 student uprising in an unnamed country that seems to be somewhere in eastern Europe, a successful doctor (Michael Gambon) is holding his annual dinner for three of his former schoolmates and recounting in flashbacks the story of his sexual obsession with a schoolteacher (Sonia Braga) who despises him but now lives with him as his slave. As his three male guests relate their own sexual secrets and soldiers and police periodically break into the house, the pattern of an after-dinner parable laced with vague allegorical undertones gradually takes shape. The results are engaging (if unpleasant) as story-telling — and alternately striking and pretentious as only a Roeg film can be. With Patrick Malahide, Ion Caramitru, Nickolas Grace, and John Shrapnel. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 20, 1999). — J.R.

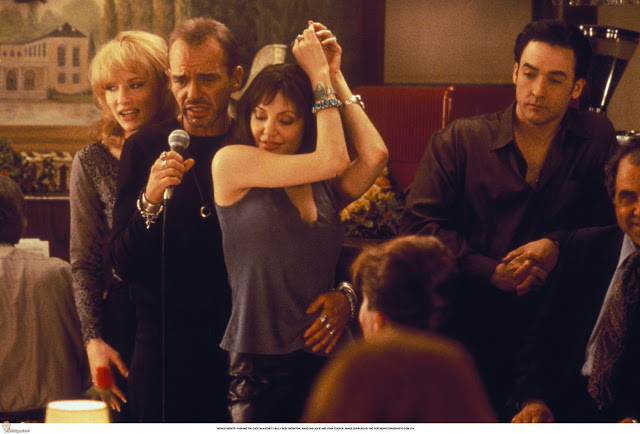

Though this comedy-drama about a macho feud between two New York air-traffic controllers (John Cusack and Billy Bob Thornton) is never entirely believable, it’s consistently lively, offbeat, and unpredictable, suggesting at times the improbable fusion of Howard Hawks and Sigmund Freud. Inspired by an article by Darcy Frey in the New York Times Magazine, the screenplay by brothers Glen and Les Charles (creators of the TV show Cheers) piles hyperbole on top of frenzy in spelling out the heroes’ frenetic lifestyle. In particular, it focuses on the putative wife swapping (involving Cate Blanchett and Angelina Jolie) that emerges from the rivalry. Cusack may be called upon to hog too much of the limelight, if only because the story is mainly told from his point of view, but director Mike Newell’s flair for mixing and matching his entire cast seldom falters. (JR)

Read more

Read more