Thanks to a post by Tom Brueggemann yesterday on Dave Kehr’s web site, I’ve just discovered the existence of a remarkable site cataloging almost 23,000 movie theaters around the world, including all nine of those in northwestern Alabama that were owned and/or operated by my grandfather between roughly 1919 and 1960, only a couple of which are still standing today (neither of which still shows movies). There’s also quite a lot of factual information about these theaters available on this site.

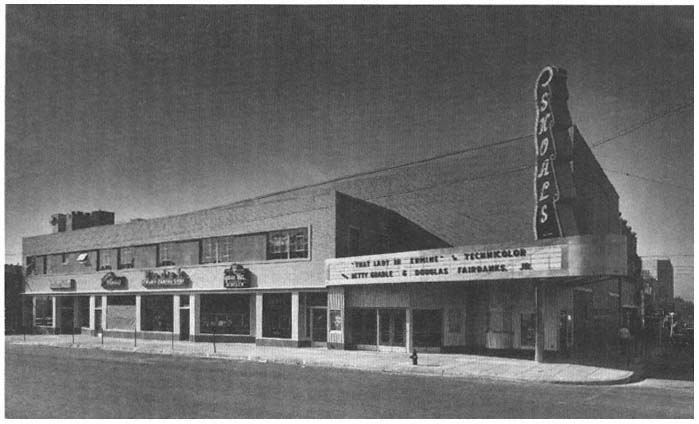

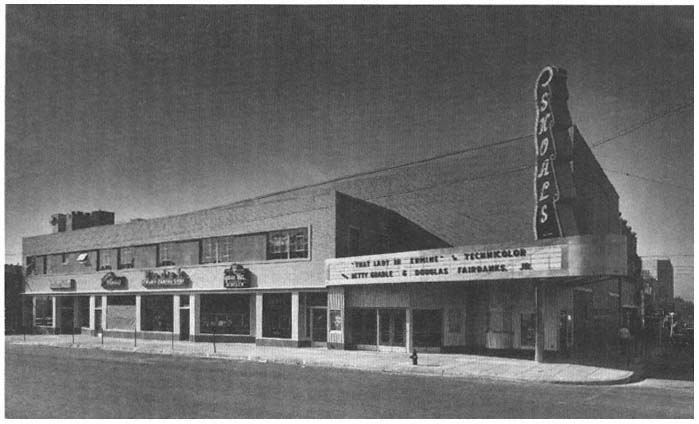

Cinema Treasures also features almost 1600 photographs of theaters, though, alas, not any of the nine run by my grandfather. It seems that the people in charge of this site got inundated with more photos of theaters than they could cope with, so they’re not currently adding any more, at least for the time being. But since a good many photos of my family’s former theaters are available in my first book, Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (1980), I’ve decided to reproduce a few here, restricting myself to exterior views of four of them. Directly overhead are the two that are still standing—the Shoals in Florence (which opened in 1948, and is seen here just after it opened) and the Ritz in Sheffield (which opened in 1928). Read more

Given my overall admiration for Elizabeth Drew as a sensible and straightforward political commentator, I’m happy to have her account in The Huffington Post of what’s dishonorable about the historical distortions of the recent Frost/Nixon movie. Even though I enjoyed the latter as middlebrow entertainment in the Stanley Kramer mode, which goaded me into ordering and watching some of the original David Frost/Richard Nixon dialogues—generally finding Ron Howard as a director to be one of the abler purveyors of this kind of dubious material, which I sometimes have a weakness for—it’s always useful to have someone like Drew pointing out the various misrepresentations.

Why, then, can’t I count on Drew to sidestep the grotesque Hollywood distortions about Nixon that automatically come with seeing him as “a tragic Shakespearean figure”—an absurd inflation that appears to have been invented by either Oliver Stone or his publicist (assuming that there’s a meaningful distinction to be made between the two) as part of the promotional campaign for his 1995 White Elephant Nixon starring Anthony Hopkins?

For me, there’s something unnerving about the way Nixon (the person) has been absurdly elevated and even validated in this cheesy fashion in order to sell a ridiculously overheated piece of merchandise, which Drew is all ready to buy into without blinking. Read more

The energetic and resourceful Gary Tooze at DVD Beaver has recently created a DVD Beaver Toolbar that, among many other useful features (such as listing the current temperature anywhere in the world–e.g., in Chicago right now, “25̊̊ F, few clouds, feels like 17̊̊”), includes a link to this web site, under Cinephilia (which so far includes only four other entries). You can also get notified about new emails, access some radio stations, and be routed to various film-related forums with this gizmo. [12/11/08] Read more

“I just don’t think America’s ready for a black president. And I don’t mean that in a racial way whatsoever.” (McCain supporter, quoted by Matt Taibbi in “Requiem for a Maverick” in the November 27 Rolling Stone) Read more

It’s great to see D.W. Griffith’s scandalously underrated and neglected last feature (1931)–already available on VHS, finally just out on DVD–recognized, and for the right reasons, by Dave Kehr in his DVD column in the New York Times today. And on Dave’s web site, he’s thoughtfully featured the above lobby card. [11/18/08] Read more

Okay, this 1952 Leo McCarey melodrama is flawed, even deranged in its second half, when the combined difficulties of Robert Walker’s sudden death during the film’s production and McCarey’s crazed view of the Communist Menace yield a creepy form of paranoid hysteria and delirium. But this is also one of the most moving and complexly felt movies McCarey ever made — also one of the best acted, especially for Walker, Helen Hayes, and Dean Jagger. Writing about Robert Warshow many years ago, Donald Phelps wrongly accused him of overrating Monsieur Verdoux but rightly accused him of underrating this film. Its continuing unavailability on DVD is a disservice both to McCarey’s memory and to his audience. [11/16/08] Read more

Far be it for me to invent wimpy liberal alibis for police corruption in 1928 Los Angeles, punitive electroshock, a pederast serial killer, and cosmic injustice in general, but the main thing wrong with Clint Eastwood’s view of evil in this movie is how childish it seems. I don’t care if he’s 78 and apparently has some fixation about innocent boys abducted by sex maniacs; even if the plot periodically suggests a remake of Mystic River, the cackling villains belong in a Hopalong Cassidy western, not to mention Dirty Harry. The opening intertitle calls this “a true story,” but whether it’s verifiable that Christine Collins was really saved from electroshock just in the nick of time by Hopalong (John Malkovich, in the film’s only interesting performance) coming to her rescue is a matter worthy of some skepticism. And even if that really happened, would it justify Angelina Jolie’s terrible Oscar-mongering performance and all the attendant grandstanding, gigantic close-ups, and directorial pretensions that this movie’s “dark” view of human existence is some form of maturity? All I could think about was the usual compulsive kid stuff–McCain and Palin fulminating about the “good guys” and “bad guys”. [11/2/08] Read more

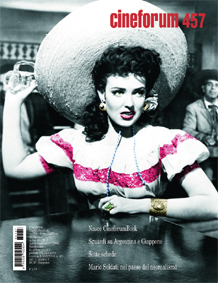

1. The preceding four images, and apparently thousands more, come from moviemags.com, “the site of movie magazines,” which Chicagoan Bill Stamets has just alerted me to. The gaps are in some ways more awesome than the inclusions, and the taste may seem closer to zines and the Video Search of Miami than to the usual library indexes and bibliographies, but there’s still a lot of information squirreled away here, and the search engine certainly helps.

2. The other site, Moving Image Source, is already mentioned elsewhere on this site because they’ve been commissioning several articles from me, and because they’ve featured an article that I’ve recommended by Chris Fujiwara. (Actually, two articles if one includes a postscript about his more recent piece on Jacques Tourneur’s Stranger on Horseback—a piece I still like, though I wish I liked the film more.) But I’d like to call attention here to two other features there, Research Guide and Calendar, both of which are invaluable. Below are abbreviated versions of two items included in each:

Pinewood Dialogues

Pinewood Dialogues

An archive with downloadable audio and transcripts of talks with filmmakers and actors, including Robert Altman, David Cronenberg, Mira Nair, Forest Whitaker, and more.

Millenium Film Journal

Millenium Film Journal

Published since 1978 by the Millenium Film Workshop, the Millenium Film Journal focuses on avant-garde cinema and practice, and covers a range of moving image technologies. Read more

If you’re already familiar with the experimental and queer cinema of English artist Derek Jarman (1942-1994), you won’t want to miss this multifaceted tribute by Isaac Julien. Built around a late interview with Jarman, it draws on a personal lecture by his actress and friend Tilda Swinton and many clips, homes movies, and other materials. On the other hand, if you’d like an introduction to his art, your time would be better spent seeing The Last of England, Edward II, or Wittgenstein. This tribute has too many cooks and too many agendas to permit easy comprehension, especially when it comes to distinguishing the brief, unidentified clips from the empathetic curlicues, voiceovers, and

commentaries of others. 76 min. (JR)

Read more

I’ve just discovered that the comment concluding my Afterword to my article about Manny Farber on this site was grievously mistaken and misinformed. So I’ve just added this letter from Patricia—written in response to a John Powers broadcast about Manny on NPR’s Fresh Air—to my Afterword as a postscript, but I also would like to highlight it here.—J.R. [8/28/08]

Dear John Powers,

Manny was not a “Conservative,” a “Libertarian,” a “Republican,” an anything. In his early twenties he tried to join the Communist Party but they didn’t want him. During WWII he tried to enlist in the army but they rejected him. After inviting him to join, it took just one meeting for the New York Film Critics Circle to ask him to leave. He came home that night saying, “They fired me.” He also told me that even a therapist in Washington had “fired him” for not working hard enough. Manny was not a Republican because he never knew any. He didn’t quarrel with them because he was never around them. He quarreled with the people he knew: artists, writers, teachers, carpenters. When he saw smugness, complacency, and superiority — and often those qualities went together — then he would get going, and separate himself from them. Read more

Manoel de Oliveira’s 1992 feature is his third related to Portuguese writer Camilo Castelo Branco, author of the novel Oliveira adapted for his masterpiece Doomed Love (1979) and a major character in Francisca (1981). Built around the author’s late correspondence before he shot himself in 1890, this is comparatively minor and minimalist, but it’s an affecting chamber piece. Oliveira slyly mixes documentary and fiction: actors appear in both contemporary and period dress, speaking alternately in first and third person, inside the author’s home (today a museum). The ironic treatment of aristocracy and romantic decadence found in Doomed Love is regrettably absent, but Teresa Madruga, as the most prominent character, Castelo Branco’s last mistress, delivers her lines with commanding passion. In Portuguese with subtitles. 74 min. (JR) Read more

Fred Camper (one-person exhibition, Caro d’Offay Gallery, 2204 W. North Avenue, Chicago, June 14th–August 1st, 2008).

I haven’t attended this yet because it doesn’t even start until tomorrow. But I’d like to call attention to this beautiful photograph, and to the series it concludes, “Details 1: Largo Argentina, Rome, sheet 13″. You can access the entire series by going to Fred Camper’s website and clicking on the first image in the series, here. If you keep clicking, you’ll be carried through the whole series. [6/13/08] Read more

The best works in this essential program of recent experimental shorts are the longest. Pedro Costa’s The Rabbit Hunters (2007, 23 min.), a follow-up to his 2006 Colossal Youth, performs comparable wonders with its exalted yet mournful portraits of Cape Verdeans in a Lisbon suburb. Phil Solomon’s black-and-white, animated Last Days in a Lonely Place (2007, 20 min.) magically and mysteriously combines rain, material from the video game Grand Theft Auto, and patches of sound from Nicholas Ray features. Almost as effective in bringing together the cosmic and the mundane are two ten-minute wonders, Bruce Conner’s Easter Morning (which Conner shot in 1966 and misplaced) and a 35-millimeter blowup of Larry Jordan’s 1969 Our Lady of the Sphere. And there’s provocative work by Jeanne Liotta, Gyula Nemes, and Ben Rivers. The festival continues through 6/22 at Chicago Filmmakers, the Nightingale, and other venues; see chicagofilmmakers.org/onion_fest/onion.html or next week’s Reader for more. 99 min. Thu 6/19, 8 PM, Gene Siskel Film Center. –Jonathan Rosenbaum Read more

Recommendation: Check out Naomi Klein’s article in the new Rolling Stone about surveillance in today’s China for some chilling enlightenment. [5/20/08]

Read more

Read more

Genuinely global, multicultural, and multilingual in its urban perspectives, this lively documentary features graffiti artists talking about their work and illustrates their discourse with images shot in Philadelphia, New York, Los Angeles, Berlin, Hamburg, Amsterdam, Paris, Barcelona, Cape Town, Sao Paolo, Tijuana, and Tokyo. Filmmaker Jon Reiss also occasionally gives voice to people trying to eradicate graffiti. The relentless quick cutting and pop soundtrack are counterbalanced by the artists’ personalities and sociopolitical credos. Unlike Michael Glawogger’s more visionary Megacities (1998), this offers neither city symphonies nor overarching theses, but as the title suggests, the theme of rebellion predominates. Subtitled. 93 min. (JR) Read more