My idea of hell is being forced at gunpoint to resee this 1981 atrocity (also known as Beatlemania, the Movie) based on a terrible stage musical. The basic idea is to feature impersonators of John, George, Paul, and Ringo performing tenth-rate versions of their songs and to make pretentious commentaries about their historical significance. Don’t say I didn’t warn you. Directed by Joseph Manduke; with Mitch Weissman, Ralph Castelli, David Leon, and Tom Teeley. (JR) Read more

Hardly Working

After a decade’s absence, Jerry Lewis made his comeback in 1981 with this movie, which represents a throwback in some respects to the conditions of his first film as a director, The Bellboy: a low budget, discontinuous gags, and Florida locations (in this case suburban). But two decades separate that film from this one, and what Lewis comes up with here is both looser and more tragicnot merely in depicting the vain efforts of an out-of-work circus clown to hold down a steady blue-collar job, but in showing the effects of aging and lessened stamina in its star (reflected also in the tired, memorable features of Lewis’s straight man, Harold J. Stone, who plays his boss at the post office and the father of his girlfriend). The candor of this movie as self-portrait is at times almost terrifying; while some of the gags are genuinely funny, the depiction of an older Lewis trying to adjust to everyday American life also becomes a searing depiction of the fate of misfits in the Reagan era. Lewis has described this as his worst movie, but it also may be his most revealing one. With Susan Oliver and Steve Franken. (JR) Read more

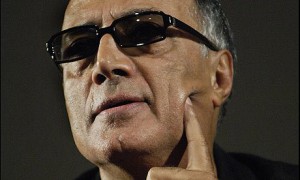

Philosophical Treatises of a Master Illusionist: A Conversation about Abbas Kiarostami

This is a slightly different edit of a dialogue proposed and inaugurated by Ehsan Khoshbakht on July 5, 2016, edited by him, and published in the British Council’s online Underline magazine on July 8. — J.R.

Abbas Kiarostami (1940-2016), arguably the greatest of Iranian filmmakers, was a master of interruption and reduction in cinema. He, who passed away on Monday in a Paris hospital, diverted cinema from its course more than once. From his experimental children’s films to deconstructing the meaning of documentary and fiction, to digital experimentation, every move brought him new admirers and cost him some of his old ones. Kiarostami provided a style, a film language, with a valid grammar of its own. On the occasion of this great loss, Jonathan Rosenbaum and I discussed some aspects of Kiarostami’s world. Jonathan, the former chief film critic at Chicago Reader, is the co-author (with Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa) of a book on Kiarostami, available from the University of Illinois Press. – Ehsan Khoshbakht

Ehsan Khoshbakht: Abbas Kiarostami’s impact on Iranian cinema was so colossal that it almost swallowed up everything before it, and to a certain extent after it. For better or worse, Iranian cinema was equated with Abbas Kiarostami. Read more

Agatha

Subtitled The Unlimited Readings, this 1981 Marguerite Duras feature is one of her most strongly minimalist, consisting mainly of an offscreen poetic dialogue between a sister and brother about their memories and their incestuous feelings for each other (spoken by Duras and her companion Yann Andrea) and shots of empty beaches and a virtually deserted hotel lobby where one occasionally glimpses Bulle Ogier (and, less often, Andrea). The results are not devoid of interest, but far less absorbing and resonant than Duras’ India Song and Le camion. (JR) Read more

Valley Of Abraham

Portuguese filmmaker Manoel de Oliveira directed this 187-minute feature (1993), his 13th, in his mid-80s. His adaptation of a novel written at his suggestion by Agustina Bessa-Luis (who also wrote the source novel for Oliveira’s 1981 masterpiece Francisca) is largely a pastiche of Madame Bovary transposed to an upper-class Portuguese and 20th-century milieu, with a detailed offscreen narration that reeks of 19th-century fiction. Oliveira is both a high modernist and a Victorian aristocrat, which makes him paradoxically something of an opulent minimalist, and this beautifully shot, slow-moving, talky meditation on a life of leisure led by an adulterous woman differs most radically from Flaubert’s novel in its indifference to the middle class. There’s also a very modern and ironic attitude toward representation that leads Oliveira to emphasize the difference in the appearances of the two actresses who play the heroine at different ages. With Leonor Silveira, Cecile Sanz de Alba, and Luis Miguel Cintra. In Portuguese with subtitles. (JR) Read more

Lights up! A few final words on the [New York] film festival [in 1981]

From the Soho News, October 20, 1981. Girish Shambu’s post on Facebook about Jacques Rivette’s Le Pont de Nord having “just popped up at both MUBI and Fandor on streaming” led me to unearth my original review of the film, which I’ve neglected to scan or post before now. — J.R.

At a juncture like this. the New York festival splits into disassociated sections for me. One part furnishes a launching pad for a commercial venture that scarcely needs it, while the other is furnishing us with a tantalizing glimpse of movies that something called Commerce is otherwise steadily denying us. (Mutatis mutandis, the same can be said for the highly uneven collection of shorts shown with the festival features. It’s hard to know when or if my own two favorites — George Griffin’s Flying Fur, a wild burst of contemporary animation energy set to an old Tom and Jerry soundtrack, and Clare Peploe’s beautifully shot comic English sketch, Couples & Robbers, about a middle-class straight couple and an upper-class gay couple and how their lives and goods interact –- might turn up again, so I’m grateful to the festival for letting me see them.)

With Truffaut’s La Femme d’à côté (The Woman Next Door) and Jacques Rivette’s Le Pont du nord (North Bridge), both New Wave veterans are giving us mixtures that we’ve seen in their works before. Read more

The Traveller

This first feature by Iranian master Abbas Kiarostami launches an indispensable, if less than complete, retrospective for one of the world’s greatest living filmmakers. Made in 1974, the film tells the story of a village boy who’s determined to attend a soccer match in Tehran, a venture that involves swiping or scamming money from various sources and in effect running away from home. The comparison that many have made between this touchingly nonjudgmental and often comic short feature and The 400 Blows isn’t far off, and Kiarostami’s warm, poetic feeling for children and his flair for both storytelling and documentarylike detail are already fully in place. On the same program are two of Kiarostami’s conceptual short films (many of which recall Jane Campion’s experimental Passionless Moments in both essayistic content and formal brio), made respectively in 1975 and 1981. I’ve seen So I Can (an obtuse inversion of the original title that translates simply “so can I”), which deftly mixes animation and live action, and look forward to seeing Regularly or Irregularly, which reportedly treats schoolroom behavior in a highly formal manner. Film Center, Art Institute, Columbus Drive at Jackson, Saturday, June 1, 6:00, and Sunday, June 2, 2:00, 443-3737. –Jonathan Rosenbaum Read more

Festival Journal: N.Y. Film Festival, 1981

From The Soho News, October 6, 1981. I’m embarrassed to confess that over three decades later, I have no recollection at all about Tighten Your Belts, Bite the Bullet apart from what I wrote about it, although I’m happy to report that the film is still in distribution, and available from Icarus Films. — J.R.

September 22: From a global or even a continental perspective, much of this year’s New York Film Festival belongs under the staunch division of Business as Usual. This basically means that the festival is involved in ratifying certain important discoveries (of ideas or filmmakers) that were made during the 60s or 70s, often by the very same members of the selection committee, rather than risking its self-image or self-composure in order to seek out many new challenges or talents.

This makes New York precisely the reverse of the more footloose, friendly, and unpredictable film festival in Toronto. There the specialty tends to be, rather, a flavorsome if occasionally warmed-over newness of look, sound, and/or signature: an underground movie about everyday life in the Watts ghetto (Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep), a corrosive and shocking black comedy about the mourning business in Israel in relation to war memorials (Yaky Yosha’s The Vulture), a flaky German film based on a French best seller about Proust by his maid, played by Fassbinder alumnus Eva Mattes (Percy Adlon’s Celeste). Read more

Cutter’s Way

This powerful paranoid thriller set in Santa Barbara, adapted by Jeffrey Alan Fishkin from Newton Thornberg’s novel Cutter and Bone (the film’s original title), is probably Ivan Passer’s best American feature (1981, 105 min.). Jeff Bridges and John Heard play two friends, the latter a crippled Vietnam war veteran, who stumble upon what looks like a murder committed by a wealthy local citizen. A major statement about post-60s disillusionment, with a wonderful performance by Lisa Eichhorn and shimmering, hallucinatory cinematography by Jordan Cronenweth. (JR) Read more

Basquiat

Painter Julian Schnabel’s 1996 biopic about Jean-Michel Basquiat (Jeffrey Wright), a black graffitist in New York who became famous in 1981 and died seven years later. Art critic Robert Hughes titled his obituary for Basquiat Requiem for a Featherweight, and part of what’s so interesting and unexpected about this picture is that it makes fresh observations without refuting that judgment. It’s also quite energeticthere isn’t a boring shot anywhere, and writer-director Schnabel is clearly enjoying himself as he plays with expressionist sound, neo-Eisensteinian edits, and all sorts of other filmic ideas. What emerges may be unfocused as narrative, but it’s lively as filmmaking. Others in the cast include David Bowie as Andy Warhol, Michael Wincott as Rene Ricard, Paul Bartel as Henry Geldzahler, and Elina Lowensohn as art dealer Annina Nosei; the actors playing fictional characters include Gary Oldman (as an apparent stand-in for Schnabel himself), Christopher Walken (in a brilliant bit as a slimy interviewer), Willem Dafoe, and Courtney Love. 108 min. (JR) Read more

Steve Lacy: Lift the Bandstand/Jackie McLean on Mars

The problem with most jazz documentaries is combining talk with music without allowing either to ride roughshod over the other. Peter Bull’s recent feature about Thelonious Monk disciple and soprano saxophonist Steve Lacy is a stirring object lesson in how to do this without compromising either the performances of Lacy’s inventive sextet or the interest in what Lacy has to say about his career. The mesh isn’t quite so fine in Ken Levis’s short about another postbebop saxophonist. Jackie McLean has some acute things to say about politics, racism, and the music business, but it’s a drag to hear them interrupting his solos; only in an outtake from Shirley Clarke’s The Connection is he allowed to stretch a little. (Film Center, Art Institute, Columbus Drive at Jackson, Sunday, August 23, 6:00 and 8:00, 443-3737) Read more

Amazon Women On The Moon

Virtually a sequel to John Landis’s Kentucky Fried Movie, this collection of comic sketches (1987), most of them TV and grade-Z movie parodies, was written by Michael Barrie and Jim Mulholland and directed by several hands: Joe Dante, Carl Gottlieb, Peter Horton, Landis, and producer Robert K. Weiss. Like most such ventures, it’s pretty hit-or-miss, with Dante and Weiss providing most of the energy; Horton is competent (in a single bit with Rosanna Arquette and Steve Guttenberg), Gottlieb routine, and Landis is OK with sight gags but somewhat adrift in satire. Overall, too many of the ideas –e ven some of the better ones — are paranoid derivations from either Sherlock Jr. (by way of Woody Allen) or Paul Bartel’s The Secret Cinema, and too many of the objects satirized are easy targets. The strongest aftertaste is left by Dante’s bad-taste rendition of movie critics reviewing a failed life, a sequence that eventually turns into a celebrity roast for the dead person, attended by Slappy White, Jackie Vernon, Henny Youngman, Charlie Callas, and Steve Allentoo sinister for comfortable laughs, but queasy in the best Dante manner. (Other stars in cameos include Ralph Bellamy, B.B. King, Griffin Dunne, and Michelle Pfeiffer.) Read more

No Man’s Land

The title of Alain Tanner’s melancholy 1985 film refers to the rural zone between Swiss and French customs, where a group of small-time smugglers eke out a precarious, in-between existence. Films about border tensions (Grand Illusion, Touch of Evil, Luc Moullet’s unjustly neglected Les contrebandieres) tend to treat their locations metaphorically, and this one is no exception, although it’s equally a Losers’ Club movie in the manner of The Asphalt Jungle about a band of assorted malcontents who dream of escape to a better life. Decorously framed and shot, with lingering landscape shots, stately camera movements, and a wonderful Terry Riley score, this movie glides along with a kind of graceful inertia that eventually defeats its spectators as well as its characters by gradually leading both to the same inconclusive impasse. With Hughes Quester, Myriam Mazieres, and Jean-Philippe Ecossey. (Facets Multimedia Center, 1517 W. Fullerton, Friday and Saturday, August 28 and 29, 7:00 and 9:00; Sunday, August 30, 5:30 and 7:30; and Monday through Thursday, August 31 through September 3, 7:00 and 9:00; 281-4114) Read more

Summer Night

The full title of this Lina Wertmuller effort is Summer Night With Greek Profile, Almond Eyes & Scent of Basil. It’s more or less Swept Away II, with Michele Placido’s Sicilian kidnapper replacing Giancarlo Giannini’s deckhand, and Mariangela Melato playing an even richer member of the ruling class, who has the kidnapper kidnapped and brought to her lushly appointed island to launch some retribution and, eventually, some sexual games. Wertmuller remains as cheerfully cynical and vulgar as ever about class warfare, but to call her a thinking director, as some American critics were wont to do in the 70s, would be like applauding Sylvester Stallone for his semiological insights. Try to imagine an Ayn Rand epic recast as bawdy farce and you might get a rough idea of the sensibility on view; the lack of self-consciousness, which lends a certain thrust to the opening reels, eventually leads to tedium as the central conceit gets spun out endlessly. With Roberto Herlitzka and Massimo Wertmuller. (JR) Read more

The Man Who Envied Women

It’s strange to recall that as a modern dancer and choreographer, Yvonne Rainer was known throughout the 60s and early 70s as a minimalist. For the past 15 years, she has been making experimental quasi-narrative films of an increasing multitextual density, culminating in this angry, vibrant film of 1985, which, in her own words, takes on “the housing shortage, changing family patterns, the poor pitted against the middle class, Hispanics against Jews, artists and politics, female menopause, abortion rights. There’s even a dream sequence.” Working with the speech and writing of over a dozen figures, ranging from Raymond Chandler to Julia Kristeva, Rainer also confronts and parodies male theoretical discourse (Michel Foucault in particular, sampled and discussed in extended chunks) as a mode of sexual seduction. Politics have been present in all her features, but usually folded into so many distancing devices that they mainly come out dressed in quotes. Here she allows the politics to speak more directly and eloquently, and it charges the rest of the film like a live wire–rightly assuming that we could all use a few jolts. (Film Center, Art Institute, Columbus Drive at Jackson, Thursday, September 10, 6:00, 443-3737) Read more