From the Chicago Reader (March 26, 1996). — J.R.

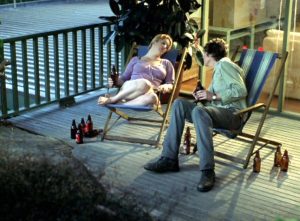

David O. Russell, the writer-director of Spanking the Monkey, offers another naughty comedy — this one less independent and much more farcical (1996), with more familiar names in the cast. A young east-coaster (Ben Stiller) with a wife (Patricia Arquette) and baby son is contacted by a psychologist (Tea Leoni) who wants to reunite him with his biological parents — whom he hasn’t seen since infancy — and videotape the results for her research. After attempting to placate his adoptive parents (George Segal and Mary Tyler Moore), he and his family and the psychologist all take off cross-country. The results are watchable enough — sometimes funny, sometimes over the top — and fairly fresh, though also a bit calculated. Leoni has an interesting comic presence one would like to see in toothier material, though this certainly has a few bites. With Alan Alda, Lily Tomlin, and Richard Jenkins. R, 92 min. (JR)