From the Chicago Reader (October 4, 2007). — J.R.

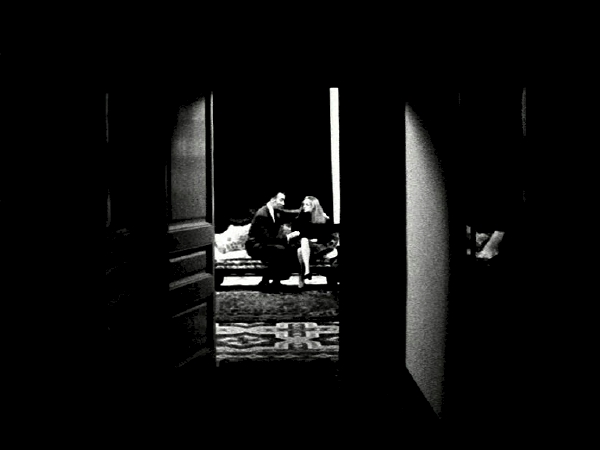

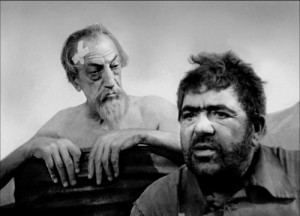

After the more complicated story lines of Satantango and Werckmeister Harmonies, Hungarian master Bela Tarr boils a Georges Simenon novel down to a few primal essentials: a railway worker in a dank and decaying port town witnesses a crime while stationed on a tower and then stumbles into some of the resulting situations. It’s a film about looking and listening, with a suggestive minimalist soundtrack and ravishing black-and-white cinematography by German filmmaker Fred Kelemen. Tarr’s slow-as-molasses camera movements and endlessly protracted takes generate a trancelike sense of wonder, giving us time to think and always implying far more than they show. (As Tarr himself puts it, The camera is inside and outside at the same time.) The fine cast includes Tilda Swinton and Hungarian actress Erika Bok, who played in Satantango when she was 11 and is now in her early 20s. In Hungarian with subtitles. 135 min. (JR)