From the Chicago Reader (October 24, 1997). — J.R.

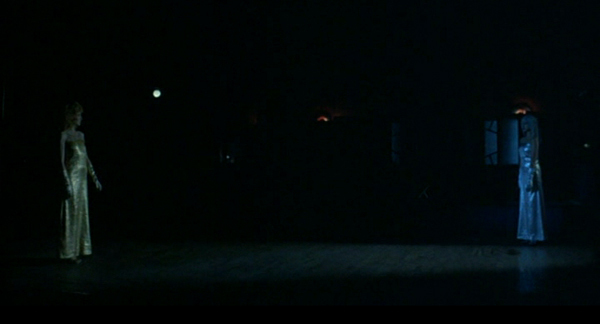

Chantal Akerman by Chantal Akerman

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Chantal Akerman.

This weekend the Museum of Contemporary Art, as part of its exhibit “Hall of Mirrors: Art and Film Since 1945,” is presenting not only Chantal Akerman, one of the finest filmmakers working anywhere, but also the two features I would describe as her greatest achievements — the 200-minute narrative Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) and the 107-minute documentary From the East (D’est, 1993). To make the program even more fully rounded, the museum is also showing a 64-minute self-portrait, Chantal Akerman by Chantal Akerman (1996), which provides an excellent introduction to her work as a whole. (This film and Akerman herself will appear on Sunday; From the East shows on Friday, and Jeanne Dielman on Saturday.)

Despite her significant and still growing international reputation, Akerman isn’t yet considered an “established” mainstream or avant-garde artist, because many critics in both spheres still treat her as something of an interloper, even an irritation or a threat. A friend who’s a highly respected novelist and film critic recently told me that he regards all her work as worthless, even though he hasn’t bothered to look at all of it. Read more