An American in Paris [ROUND MIDNIGHT]

2021 note: In part because I had unkind things to say about his first feature in 1974, writing at the time from Paris, my relations with Bertrand Tavernier (1941-2021) tended to be strained, even though both of us periodically tried to overcome this rift — and, to his credit, he was the one who made the first friendly gesture, inviting me to join him for a meal in Chicago many years later.. Round Midnight is probably the film of his that has affected me the most, which is why I’m reposting this piece now.

Part of my 1987 application for the job of film reviewer at the Chicago Reader consisted of writing three long sample reviews for them in March and/or April — only one of which was published by them (Radio Days), although, as I recall, they paid me for all three. (Writing these pieces in Santa Barbara, I was limited in my choices of what I could write about.) I only recently came across the two unpublished reviews, of Platoon and Round Midnight, in manuscript, although I recall that I did appropriate certain portions of them in subsequent reviews. Otherwise, the first publications of these pieces are on this site. Read more

Addressing the Present (2009)

This is the 11th one-page bimonthly column that I published in Cahiers du Cinéma España; it appeared in their March 2009 issue. — J.R.

Tomorrow I start teaching the final semester of a course and film series I’ve been offering at Chicago’s School of the Art Institute devoted to world cinema of the 30s, 40s, 50s and 60s. To provide a segue between the Depression of the 30s and the 40s, I’ll be starting with a double feature devoted to economic desperation, Preston Sturges’s Christmas in July (1940) and Edgar G. Ulmer’s Detour (1945).

Two of the most popular films I showed last fall were Lubitsch’s The Man I Killed (1932) and McCarey’s Make Way for Tomorrow (1937). I selected them before last year’s economic recession started, and the congruence and relevance of certain themes — remorse about warfare and spurious patriotism, crowded family apartments and neglect of the elderly — probably added to their appeal. But the contemporary impact of films is always difficult to predict. I’m convinced that a significant part of what inspired Clint Eastwood to make Flags of Our Fathers and Letters from Iwo Jima was the U.S. occupation of Iraq, but this relevance wasn’t discussed in the press. Read more

The World in a Beijing Theme Park

From the Chicago Reader (July 29, 2005). — J.R.

The World

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed and Written by Jia Zhang-ke

With Zhao Tao, Chen Taishen, Jing Jue, Jiang Zhongwei, Huang Yiqun, Wang Hongwei, Liang Jingdong, Ji Shuai, and Alla Chtcherbakova

The title of Jia Zhang-ke’s 2004 masterpiece, The World — a film that’s hilarious and upsetting, epic and dystopian — is an ironic pun and a metaphor. It’s also the name of the real theme park outside Beijing where most of the action is set and practically all its characters work. “See the world without ever leaving Beijing” is one slogan for the 115-acre park, where a monorail circles scaled-down replicas of the Eiffel Tower, the Taj Mahal, London Bridge, Saint Mark’s Square, the Leaning Tower of Pisa, the Pyramids, and even a Lower Manhattan complete with the Twin Towers. Extravagant kitsch like this may offer momentary escape from the everyday, but Jia is interested in showing the everyday activities needed to hold this kitsch in place as well as the alienation in this displaced world — and therefore in the world in general, including the one we know.

Jia, with his choreographed wide-screen long takes in long shot, may be the best cinematic composer of figures in landscapes since Michelangelo Antonioni. Read more

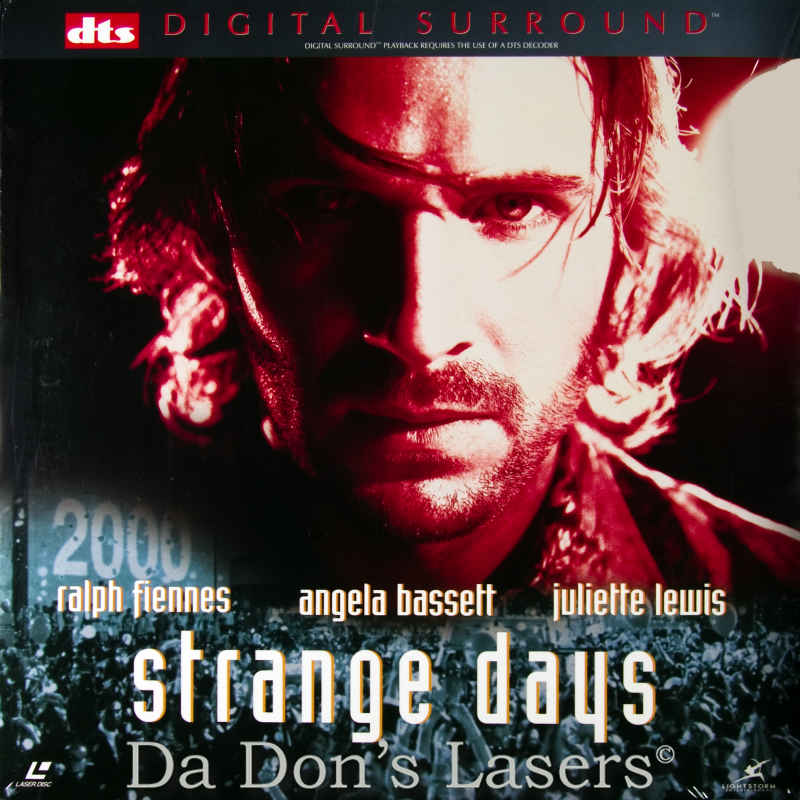

Action and Distraction (STRANGE DAYS)

From the Chicago Reader (October 27, 1995). — J.R.

Strange Days

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Kathryn Bigelow

Written by James Cameron and Jay Cocks

With Ralph Fiennes, Angela Bassett, Juliette Lewis, Tom Sizemore, Michael Wincott, Vincent D’Onofrio, Glenn Plummer, Brigitte Bako, and Richard Edson.

In the introduction to his recently published first draft of the Strange Days screenplay, James Cameron offers a candid, suggestive description of what working on the script was like: “The problem was I had never written anything remotely this densely plotted and character driven. I circled and circled the computer, like a dog slinking around trying to work up the courage to steal food from a sleeping drunk.”

Cameron’s simile could be seen to apply not so much to Strange Days and other overhyped media events as to the sort of measures our legislators have been pushing through Congress lately. These measures more or less state that we can no longer afford to coddle criminals, the elderly, crack babies, the poor, the sick, or the homeless or support art, culture, or education — not because we’re living through any kind of depression but because millionaires still aren’t making as much money as they want to. Assuming that we’re the sleeping drunk in this scenario, it’s worth asking what sort of dreams we could possibly be having that would allow those congressional canines to find the courage to slink around us with this kind of hope. Read more

DAISIES (1966)

This was written in the summer of 2000 for a coffee-table book edited by Geoff Andrew that was published the following year, Film: The Critics’ Choice (New York: Billboard Books). I’m delighted that this feature and many others by Chytilová (including, most recently, her long-neglected Something Different) are now available in excellent DVD editions from Second Run in the U.K. — J.R.

My favorite Czech film, one of the most exhilarating stylistic and psychedelic explosions of the 1960s, is Vera Chytilová’s highly aggressive feminist farce Daisies, which erupts in all directions. At any given moment, shots can switch from luscious color to black-and-white to sepia to a rainbow succession of color filters, shatter into shards like broken glass, rattle through rapid-fire montages like machine-gun volleys, and leap freely between time frames and locations. While many American and Western European filmmakers during this period prided themselves on their subversiveness, it is quite possible that the most radical film of the decade, ideologically as well as formally, came from the East — from the liberating ferment building towards the short-lived political reforms of 1968’s Prague Spring.

Featuring two giggling, nihilistic 17-year-olds, both named Marie — a brunette (Ivana Karbanova) and a redhead (Jitká Cerhova) — Daisies does not have a narrative or even characters in the ordinary sense: Just a good deal of provocation that typically garners more laughter from the women in the audience than the men. Read more

Daney in English: A Letter to Trafic

Written for and originally published (in French translation) in Trafic no. 37 (printemps 2001); also reprinted in my 2010 collection Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia. — J.R.

Chicago, November 13, 2000

Dear Jean-Claude, Patrice, Raymond, and Sylvie,

Trying to find a useful way to discuss Serge Daney in an Anglo-American context, it’s hard not to feel a little demoralized. I recently looked up the letter I wrote to a university press editor in early 1995, not very much shorter than this one, enumerating -– to no avail -– all the reasons why bringing out a collection of Serge’s film criticism in English was an urgent matter and a first priority, almost comparable in some ways to what making Bazin available in English had been in the ’60s.

I believe this might have been the longest “reader’s report” I’ve ever written for a publisher. I was trying to persuade the editor to publish a translation of Daney texts that in fact had already been commissioned and completed in England, but, for diverse reasons, had never appeared in print. All the texts chosen came from Ciné journal and Devant la recrudescence des vols de sacs à main. I thought this translation needed some revision to make it more graceful and user-friendly, and I would have preferred a broader selection. Read more

City Of Sadness

From the May 1, 2001 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

This beautiful family saga by the great Taiwanese filmmaker Hou Hsiao-hsien begins in 1945, when Japan ended its 51-year colonial rule in Taiwan, and concludes in 1949, when mainland China became communist and Chiang Kai-shek’s government retreated to Taipei. Perceiving these historical upheavals through the varied lives of a single family, Hou again proves himself a master of long takes and complex framing, with a great talent for passionate (though elliptical and distanced) storytelling. Given the diverse languages and dialects spoken here (including the language of a deaf-mute, rendered in intertitles), this 1989 drama is largely a meditation on communication itself, and appropriately enough it was the first Taiwanese film to use direct sound. It’s also one of the supreme masterworks of the contemporary cinema, the first feature of Hou’s magisterial trilogy (followed by The Puppet Master and Good Men, Good Women) about Taiwan during the 20th century. In Mandarin and Taiwanese with subtitles. 160 min. (JR)

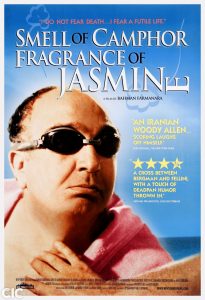

Smell of Camphor, Fragrance of Jasmine

From the September 7, 2001 Chicago Reader. — J.R,

One of the more interesting personalities of the Iranian cinema, Bahman Farmanara produced a controversial early feature by Abbas Kiarostami (Report) and won praise for his own work, including the 1974 feature Prince Ehtejab. But he hit a government roadblock in the mid-70s, when all his proposals for films started getting rejected, and for much of the past quarter century he’s lived in the West (in Vancouver, among other places). In this welcome comeback (2000) he plays a middle-aged filmmaker rather like himself who ruefully accepts a commission to make a documentary for Japanese television about Iranian death rituals. His wife has been dead five years (though Farmanara’s wife, to whom the film is dedicated, is alive and well), and after discovering that the cemetery where he expects to be buried has planted someone else next to her, he embarks on the strange experience of witnessing his own funeral, one of many fantasy sequences. This oddball comedy, a selection at last year’s New York film festival, is full of wry asides and unexpected details that tell us more about contemporary Iran than we’d normally expect to find in a recent feature. Read more

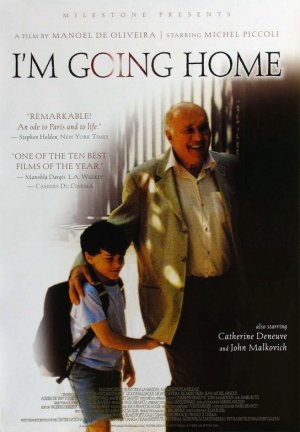

Patience Pays Off [I’M GOING HOME]

From the Chicago Reader (September 13, 2002). — J.R.

I’m Going Home

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed and written by Manoel de Oliveira

With Michel Piccoli, Antoine Chappey, Catherine Deneuve, John Malkovich, Leonor Baldaque, and Sylvie Testud.

It seems entirely fitting that I’m Going Home — a beautiful feature by Manoel de Oliveira, who turns 94 this December and is still going strong — should open in Chicago, at the Music Box, just after September 11. This 2001 French film by a Portuguese master who occasionally makes films in France is the kind of quiet masterpiece that fully registers only after you’ve seen it — a profound meditation on bereavement and other kinds of loss (including losing one’s way) as well as on everyday life and things right under our noses that we accept as “other,” including old age and art and different cultures.

The French DVD of this film has an interview with Oliveira in Portuguese, subtitled in French, in which he explains what this movie means to him. He speaks alternately about the film’s plot, which he calls a tragedy, the real incident that inspired it (a famous actor in his 70s forgot his lines while shooting a film), and what he calls the “tragedy of our civilization.” Read more

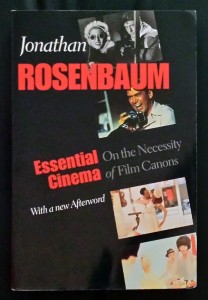

1000 Favorites (A Personal Canon), part three

This is the third part of the Appendix of my 2004 collection Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons. — J.R.

1000 Favorites (A Personal Canon), Part 3

The criteria I’ve used for inclusion on this list are pleasure and edification; I haven’t factored in any sense of historical importance that might exist independently of these factors. I’ve incorporated shorts as well as features, both animation and live-action, and videos as well as some works made for television, but not anything made for a TV series.

Broadly speaking, this list would comprise what I’d want to have on a desert island were it not for the fact that I’d want to bring along many other things that I haven’t already seen — including some of my more conspicuous omissions. No one who claims to have seen all possible candidates for the greatest films ever made could possibly be telling the truth, even in relation to a single year, and many of the exclusions here are things I haven’t yet caught up with. Many others are absent simply because I don’t value them as much as those I’ve included, and the most obvious limitation of this list is that it won’t be apparent in most cases whether I’ve excluded something because I haven’t seen it or because I don’t rank it highly enough. Read more

1,000 Favorites (A Personal Canon), part two

This is the second part of the Appendix of my 2004 collection Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons. — J.R.

1000 Favorites (A Personal Canon), Part 2

The criteria I’ve used for inclusion on this list are pleasure and edification; I haven’t factored in any sense of historical importance that might exist independently of these factors. I’ve incorporated shorts as well as features, both animation and live-action, and videos as well as some works made for television, but not anything made for a TV series.

Broadly speaking, this list would comprise what I’d want to have on a desert island were it not for the fact that I’d want to bring along many other things that I haven’t already seen — including some of my more conspicuous omissions. No one who claims to have seen all possible candidates for the greatest films ever made could possibly be telling the truth, even in relation to a single year, and many of the exclusions here are things I haven’t yet caught up with. Many others are absent simply because I don’t value them as much as those I’ve included, and the most obvious limitation of this list is that it won’t be apparent in most cases whether I’ve excluded something because I haven’t seen it or because I don’t rank it highly enough. Read more

1,000 Favorites (A Personal Canon), part one

This is the first part of the Appendix of my 2004 collection Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons. — J.R.

1000 Favorites (A Personal Canon), Part 1

The criteria I’ve used for inclusion on this list are pleasure and edification; I haven’t factored in any sense of historical importance that might exist independently of these factors. I’ve incorporated shorts as well as features, both animation and live-action, and videos as well as some works made for television, but not anything made for a TV series.

Broadly speaking, this list would comprise what I’d want to have on a desert island were it not for the fact that I’d want to bring along many other things that I haven’t already seen — including some of my more conspicuous omissions. No one who claims to have seen all possible candidates for the greatest films ever made could possibly be telling the truth, even in relation to a single year, and many of the exclusions here are things I haven’t yet caught up with. Many others are absent simply because I don’t value them as much as those I’ve included, and the most obvious limitation of this list is that it won’t be apparent in most cases whether I’ve excluded something because I haven’t seen it or because I don’t rank it highly enough. Read more

Acid Western

From the Chicago Reader (June 28, 1996). This essay subsequently grew into a book, commissioned by Rob White for the BFI Modern Classics, that came out in 2000, proved to be one of my most popular, and went into a second edition; a French edition is also available (2005), translated by Louis Malle’s daughter Justine, as well as a Czech edition and even an unauthorized Farsi one. — J.R.

Dead Man

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed and written

by Jim Jarmusch

With Johnny Depp, Gary Farmer, Lance Henriksen, Michael Wincott, Eugene Byrd, Mili Avital, Gabriel Byrne, John Hurt, Iggy Pop, Billy Bob Thornton, Jared Harris, Jimmie Ray Weeks, Mark Bringelson, Michelle Thrush, Alfred Molina, Robert Mitchum, and Crispin Glover.

When we speak of “seriousness” in fiction ultimately we are talking about an attitude toward death. — Thomas Pynchon

Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man, a disturbing, mysterious black-and-white western, opens with someone named William Blake (Johnny Depp), a recently orphaned accountant from Cleveland, traveling west on a train with the promise of a job at a metal works in a town called Machine. He keeps dozing off and waking to new sets of fellow passengers, including several who fire their guns out the windows at a herd of buffalo. Read more

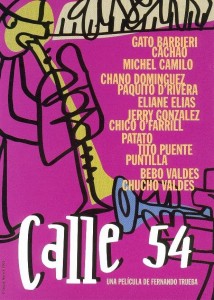

Calle 54

From the Chicago Reader (May 1, 2001). — J.R.

This no-nonsense documentary (2000) by the Spanish director Fernando Trueba (an Oscar winner for Belle Epoque) is a welcome primer on Latin jazz, an expansive genre that can range from a Dizzy Gillespie big-band arrangement to a Charlie Haden ballad. If my eyes aren’t deceiving me, the minimal exterior footage of musicians, shot in the U.S., Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Sweden, is digital video while the much slicker footage in simple studio settings is on celluloid — an appropriate combination, even if there’s a bit too much restless MTV-like cutting and angle changing. Much more importantly, Trueba’s commentaries are brief and to the point, and are never delivered over the music. A celebration of visual as well as aural delights, the film amply demonstrates how playing certain percussive instruments — conga drums, vibes, even piano — is much like dancing (though Trueba also provides actual dancing to go with Chano Dominguez’s jazz-flamenco fusions near the beginning and some Afro-Cuban drumming near the end). Apart from the percussiveness, the music is extremely varied, running the gamut from Eliane Elias’s lyrical piano to Gato Barbieri’s gruff but tender tenor sax to Chico O’Farrill’s wonderful big-band scoring; among the many other featured players are Paquito d’Rivera, Jerry Gonzalez and the Fort Apache Band, Tito Puente, Chucho Valdes, and a couple of the latter’s relatives. Read more