From the November-December 1981 issue of Film Comment. I was gratified to learn from David Bordwell, via his own web site (as well as an email to me), that he’s eventually come around to agreeing with my major complaint about his book. (For an update to his link to my subsequent essay about Gertrud, go here. However, his link to this essay no longer works, so here’s one that does.)

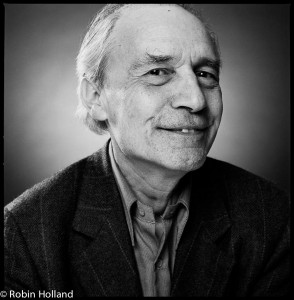

The photograph of Dreyer immediately below is by Jonas Mekas. — J.R.

The Films of Carl-Theodor Dreyer by David Bordwell. 251 pp., illustrations, index, University of California Press, $29.50

In relation to Roland Barthes’ distinction between readerly and writerly texts, David Bordwell — an academic marvel who organizes huge masses of material with an uncanny sense of what can or can’t be assimilated –- should be considered a master of the teacherly text. His ambitious textbook written with Kristin Thompson, Film Art: An Introduction (Addison-Wesley, 1979), has rightly been regarded as a landmark to many film teachers — a sort of Whole Systems Catalog of formal registers in film that, like Dudley Andrew’s The Major Film Theories, makes a good bit of relatively difficult material accessible to students. Read more