From the Chicago Reader (January 12, 1998). — J.R.

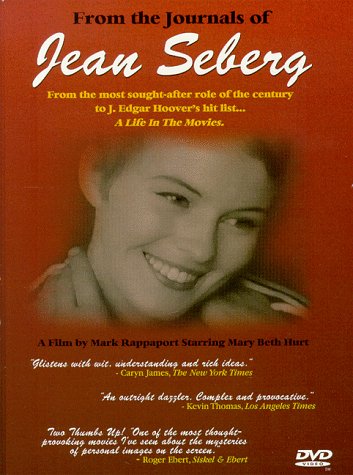

From the Journals of Jean Seberg

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed and written by Mark Rappaport

With Jean Seberg and Mary Beth Hurt.

For most of the remainder of this month the Film Center is presenting the U.S. theatrical premiere of Mark Rappaport’s From the Journals of Jean Seberg, and using this occasion to show some other important programs as well. We had revivals of Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless, featuring one of Seberg’s key early performances, and Carl Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), both important touchstones in Rappaport’s film — the second as a cross-reference to Seberg’s first film, Saint Joan. This week, in addition to seven showings of From the Journals of Jean Seberg (to be followed by four more over the next couple of weeks), there are two screenings of a brand-new print of one of Rappaport’s best narrative features, The Scenic Route (1978), along with his remarkable 36-minute tour de force Exterior Night (1994) — a noirish narrative about film noir in which actors filmed in color walk around inside vintage black-and-white Warners sets and locations from the 40s and 50s, shot originally on high-definition video in Germany, and recently transferred to 35-millimeter film. Read more