The unholy mix of George Lucas’s colonialist nostalgia and Steven Spielberg’s fluency with action becomes more self-conscious in this fourth Indiana Jones outing. In 1957, two decades after the events of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, the hero (Harrison Ford) joins forces with his old flame from Raiders of the Lost Ark (Karen Allen) and a young punk (Shia LaBeouf) to combat a Commie villain (Cate Blanchett, doing a variation on Garbo’s Ninotchka) in a remote corner of Peru. The character and plot contrivances are dumber than ever, but this is basically vaudeville, not narrative, and the thrills keep coming. (Once Indy has survived a nuclear blast early on, going over three waterfalls in a row without wetting his lighter is par for the course.) Spielberg’s extravagant action, much of it staged on what look like old sets from King Kong, includes pointed steals from The Naked Jungle (1954), Land of the Pharaohs (1955), The Ten Commandments (1956), and his own Close Encounters, E.T., and A.I. PG-13, 124 min. (JR) Read more

Read more

A View From The Past [VALLEY OF ABRAHAM]

From the Chicago Reader (August 25, 1995). — J.R.

Valley of Abraham

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Manoel de Oliveira

With Leonor Silveira, Cecile Sanz de Alba, Luis Miguel Cintra, Rui de Carvalho, Luis Lima Barreto, Diogo Doria, Jose Pinto, and Isabel Ruth.

I think the most important intellectual discovery I’ve made in the past year came from the early pages of Eric Hobsbawm’s The Age of Extremes: A History of the World, 1914-1991. In a way, it’s an observation so obvious that I wonder why it never occurred to me before: “Unlike the ‘long 19th century,’ which seemed, and actually was, a period of almost unbroken material, intellectual and moral progress…there has, since 1914, been a marked regression from the standards then regarded as normal in the developed countries and in the milieus of the middle classes and which were confidently believed to be spreading to the more backward regions and the less enlightened strata of the population….Since this century has taught us, and continues to teach us, that human beings can learn to live under the most brutalized and theoretically intolerable conditions, it is not easy to grasp the extent of the, unfortunately accelerating, return to what our 19th century ancestors would have called the standards of barbarism.” Read more

Austin Powers: International Man Of Mystery

From the Chicago Reader (May 1, 1997). — J.R.

After 30 years of cryogenic preservation, the title hero (a spin-off of James Bond and his clones) and his archenemy Dr. Evil — both played by writer and coproducer Mike Myers (Wayne’s World) — emerge in the present to match wits all over again. What’s really fun about this silly but spirited comedy isn’t just the ribbing of swinging London fashion and social attitudes but the use of the compulsive zooms and split-screen mosaics of commercial movies of the 60s (some of the funniest gags derive from camera placement). There’s a bit of fudging when it comes to the romantic interest: sidekick Elizabeth Hurley initially blanches at Austin Powers’s advances but succumbs as soon as he treats her to a night on the town in Las Vegas, complete with champagne and Burt Bacharach. But 60s (and 50s) icons like Robert Wagner and Michael York (playing someone called Basil Exposition) make this exercise in historical relativity even funnier. Jay Roach directed with just the right amount of period tackiness. With Mimi Rogers, Seth Green, and Fabiana Udenio (as Alotta Fagina). (JR)

THEY CAUGHT THE FERRY (1976 review)

From Monthly Film Bulletin, September 1976, Vol. 43, No. 512. — J.R.

De Naede Faergen (They Caught the Ferry)

Denmark, 1948

Director: Carl Th. Dreyer

Dist–Guild Sound & Vision. p.c–Ministeriernes Filmudvalg. sc–Carl Th. Dreyer. Derived from a work by Johannes V. Jensen. ph–Jørgen Roos. ed–Carl Th. Dreyer. sd–Jorgen Roos. l.p–(not credited). 408 ft. 11 mins. (16 mm.).

Behind the credits, accompanied by the ominous sound of three beats on a kettledrum, a ferry arrives at the Assens-Aarøsund landing. After some reverse-angle cuts between ferry and landing, a motorcyclist on board asks the captain about the next departure of the ferry on the other side of the island. ToId that it leaves in forty-five minutes but that he’ll never make it — the other ferry being seventy-five kilometres away — the man replies, “I must get it” and, with a female companion clinging to his waist, drives off the boat behind a line of other cyclists.

He quickly accelerates from 40 to 80 km. per hour, and his race down a country road is illustrated by moving shots which alternate his viewpoint (passing trees, close-ups of speedometer) with ‘objective’ angles (shots behind or ahead of his bike, close-ups of wheels). After stopping at a petrol station, where he urges the female attendant to hurry and she replies that he’lI have to drive fast to make the ferry. Read more

Still Life

From the Chicago Reader (January 24, 2008). — J.R.

The fifth feature by Jia Zhang-ke, China’s greatest contemporary filmmaker, is set in the vicinity of China’s immense Three Gorges, where the ongoing construction of the world’s largest dam has already forced the relocation of almost two million people. Against this epic canvas, their paths crisscrossing but never intersecting, a coal miner and a nurse (both from Jia’s home province of Shanxi) search for their former mates. This 2006 drama may seem to be worlds apart from the surreal theme-park setting of Jia’s previous film, The World, but there are similarities of theme, style, scale, and tone: social and romantic alienation in a monumental setting, a daring poetic mix of realism and lyrical fantasy, and an uncanny sense of where our planet is drifting. In Mandarin and Shanxi with subtitles. 107 min. (JR)

Early Michael Snow Shorts (1976 reviews)

From Monthly Film Bulletin, December 1976 (Vol. 43, No. 515). — J.R.

One Second in Montreal

Canada, 1969

Director: Michael Snow

Dist–London Filmmakers’ Co-op/Cinegate. p.c /p/ph/ed–Michael Snow. 612 ft. (at 16 f.p.s.) 26 mins.; (at 24 f .p.s.) 17 mins.

A series of thirty-odd black and white still photographs – all showing park sites for a projected monument in Montreal covered with blankets of snow — are rephotographed and shown in succession; the duration of each photograph on the screen progressively increases during the first section of the film, and progressively decreases during the second, which ends with a ‘flash’ repeat of the initial title card. A simple experiment in what might be described as the phenomenology of duration in relation to the viewer’s attention and grasp of detail, One Second in Montreal apparently owes its title to the fact that the combined exposure time of the original photographs adds up to only one second.

Praised somewhat hyperbolically as a “cinematic construction which plays upon the seriality of film images” (Annette Michelson) and a “snow film so silent you can hear the snow fall” (Jonas Mekas), the film is an ‘open’ work in the sense that it can be projected at either 16 or 24 frames per second. Read more

29th Chicago International Film Festival: Mired in the Present

From the Chicago Reader (October 8 , 1993). — J.R.

Let’s start with the bad news, which also happens to be the good news. With the erosion of state funding virtually everywhere and the concomitant streamlining of many film festivals toward certifiable hits — basically what an audience already knows, or worse, what it thinks it knows — there isn’t a great deal of difference anymore between the lineups of most large international festivals, including Cannes, Berlin, Venice, Toronto, and even Chicago. By and large, the critics at Toronto last month, myself included, who thought it was an unusually good festival were those who hadn’t made it to the previous three big festivals.

Some films don’t make every list, of course. Luc Moullet, probably the most gifted comic filmmaker working in France, almost never seems to attract international interest, and I was disappointed to discover that his delightful Parpaillon, which I saw in Rotterdam, was passed over by Toronto, Chicago, and New York. The same goes for Robert Kramer’s Starting Place, which I saw in Locarno — a beautifully edited and moving personal documentary about contemporary Vietnam. I’m also sorry that Hou Hsiao-hsien’s The Puppetmaster and an intriguing American independent effort called Suture, both of which I saw in Toronto, are missing from the Chicago roster. Read more

No Way Out

From the Chicago Reader (August 1, 1987). — J.R.

Kevin Costner, suffering as nobly here as in The Untouchables, plays a naval officer hired by the secretary of defense (Gene Hackman), whose mistress he has been unwittingly sharing. While credited as an adaptation of Kenneth Fearing’s novel The Big Clock (which was already made into a movie in 1948, directed by John Farrow), this taut thriller adds so many twists of its own it might be more appropriately cross-referenced with The Manchurian Candidate, even though it isn’t nearly as daffy or as mercurial. Cornball Dolby effects aside, it’s the kind of intricately plotted suspense film with juicy secondary parts (Sean Young, Will Patton, George Dzundza, Iman, Howard Duff) that used to be churned out in the 1940s; Roger Donaldson, the New Zealand director of Smash Palace, The Bounty, and Marie, delivers coproducer Robert Garland’s efficient script with more bombast than brilliance, but at least it keeps you in your seat (1987). (JR)

HELSINKI, FOREVER (A City Symphony)

An unexpected gift arrives in the mail: a subtitled preview of Peter von Bagh’s fabulous and rather Markeresque documentary (2008)—a lovely city symphony which is also a history of Helsinki (and incidentally, Finland, Finnish cinema, and Finnish pop music) recounted with film clips and paintings by three voices (two male, one of them von Bagh’s, and one female—each one reciting what seems to be a slightly different style of poetic and essayistic discourse). There are no chapter divisions on this DVD, and the continuity is more often geographical than chronological, although there’s also a lot of leaping about spatially as well as temporally. At separate stages we’re introduced to the best-ever Finnish camera movement and the best Finnish musical, are invited to browse diverse neighborhoods and eras (and to ponder contrasts in populations and divorce rates), and are finally forced to admit that a surprising amount of very striking film footage has emerged from this country and city.

Peter von Bagh—prolific film critic, film historian, and professor, onetime director of the Finnish Film Archive and current artistic director of two unique film festivals, the Midnight Sun Film Festival (held in Sodankylä, above the Arctic Circle, during what amounts to one very long day in the summer, when there’s no night) and Il Cinema Ritrovato (held soon afterwards, in Bologna)—is the man who convinced me to purchase my first multiregional VCR in the early 80s. Read more

House of Games

From the Chicago Reader (October 16, 1987). Mamet’s first feature and still his best.– J.R.

Hitchcock lives! David Mamet’s first time out as a director is a thriller about compulsive behavior and con games, done with a sureness of touch and taste that shows a better understanding of Hitchcockian obsessions than the complete works of Brian De Palma. The viewer has to adjust to Mamet’s theatrical reflexes, which impart a certain strangeness to both the performances and the staging — such as confidential conversations held within earshot of characters who don’t hear them, because the conventions of theater space are employed rather than the usual conventions of filmic space. But once past this barrier, one is easily seduced by Mamet’s storytelling gifts, which deliver a shapely script (developed with Jonathan Katz), full of its own con games and compulsions, with an adroit grasp of emphasis and pacing. Lindsay Crouse (Mamet’s wife) plays a successful upper-crust psychiatrist and author whose feelings of frustration in treating her criminally involved patients goad her into a walk on the wild side, beginning with the eponymous gambling den, with Joe Mantegna as her guide. Apart from uniformly fine performances — with Mike Nussbaum, Lilia Skala, and J.T. Read more

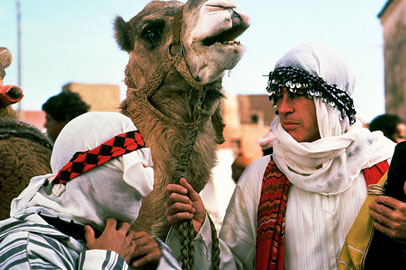

Ishtar

From the Chicago Reader (July 1, 1988). — J.R.

Treated as a debacle upon release, partially as payback for producer-star Warren Beatty’s high-handed treatment of the press, this Elaine May comedy was the most underappreciated commercial movie of 1987. It isn’t quite as good as May’s previous features, but it’s still a very funny work by one of this country’s greatest comic talents. Beatty and Dustin Hoffman, both cast against type, play inept songwriters who score a club date in North Africa and accidentally get caught up in various international intrigues. Misleadingly pegged as an imitation Road to Morocco, the film is better read as a light comic variation on May’s masterpiece Mikey and Nicky as well as a prescient send-up of blundering American idiocy in the Middle East. Among the highlights: Charles Grodin’s impersonation of a CIA operative, a blind camel, Isabelle Adjani, Jack Weston, Vittorio Storaro’s cinematography, and a delightful series of deliberately awful songs, most of them by Paul Williams. 107 min. (JR)

Go Fish

From the Chicago Reader (July 1, 1994). — J.R.

One of the delightful things about Rose Troche’s stylish, low-budget, filmed-in-Chicago black-and-white lesbian comedy is that its characters all register as real people, even when bits of the dialogue are stiff or some of the lip sync is off; this isn’t a movie about lesbians, it’s a movie about these lesbians, and we’re likely to think of them afterward as if they were people we knew. As in the better American underground movies of the 60s, which this sometimes resembles, the youthfulness and the footloose free spirit — evident in everything from the performances and Ann T. Rossetti’s shooting style to Brendan Dolan and Jennifer Sharpe’s jazz score and the breezy rhythmic stretches bridging narrative sequences — keep things bouncing along like a clear spring day. (And though the characters themselves vary in age, there’s a clear note of shared adolescent braggadocio in the way that sex and romance here become real only after they’re talked about and described.) Written as well as produced by Troche in collaboration with Guinevere Turner, the younger of the two romantic leads (the other is V.S. Brodie), this movie dives into fantasy and stylized internal monologues with the same aplomb it brings to the buildup to a hot date. Read more

Recommended Reading: Sadeq Hedayat’s THREE DROPS OF BLOOD

I find it curious that the great Iranian prose writer Sadeq Hedayat (1903-1951) should remind me so much of Edgar Allan Poe, because their backgrounds couldn’t be more dissimilar. Poe (1809-1849) was poor his entire life and Hedayat came from a very wealthy and privileged background; Poe lived in several American cities but never left the U.S. whereas Hedayat lived for extended periods in Belgium, France, and India as well as Iran.

Before the recent publication of Three Drops of Blood, a collection of Hedayat stories, I’d read only his novella The Blind Owl (1936), one of the most terrifying and unsettling horror stories I know, as well as a few of his other stories in French. It seems that most of his work is (or at least has been) available in French, but until the appearance of this slim anthology, The Blind Owl–freely if brilliantly adapted by Raul Ruiz in one of his craziest features, La Chouette Aveugle (1987)–has been virtually the only thing of his available in English. (12/25 postscript: Adrian Martin has just informed me that one can access many Hedayat stories in English translation, including The Blind Owl, for free here. Read more

Everyone Says I Love You

From the Chicago Reader (January 1, 1997). — J.R.

This creepy Woody Allen musical (1996) has got to be the best argument ever against becoming a millionaire. It unwittingly reveals so many dark facets of the filmmaker’s cloistered mind that one emerges from it as from a crypt, despite the undeniable poignance of some of the musical numbers (the best of which hark back to Guys and Dolls in displaying the vulnerability of the amateur performers). This isn’t only a matter of how Allen regards the poor, nonwhite, sick, elderly, and incarcerated segments of our society, how he feels about the ethics of privacy, or what he imagines his rich upper-east-side neighbors are like. In this characterless world of Manhattan-Venice-Paris, where love consists only of self-validation and political convictions of any kind are attributable to either hypocrisy or a brain condition, the me-first nihilism of Allen’s frightened worldview is finally given full exposure, and it’s a grisly thing to behold. With Goldie Hawn, Alan Alda, Drew Barrymore, Lukas Haas, Julia Roberts, Tim Roth, and Natalie Portman. R, 101 min. (JR)

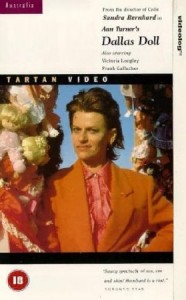

Dallas Doll

From the November 7, 1997 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

This 1994 feature is much too goofy to qualify as an absolute success, but it’s so unpredictable, irreverent, and provocative that you may not care. Australian writer-director Ann Turner has a lot on her mind, and it’s unlikely you’ll be able to plot out many of her quirky moves in advance. Imagine Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Teorema (with Sandra Bernhard in the Terence Stamp part, seducing most of a bourgeois Australian family and enough other country-club notables to wind up as mayor) crossed with Repo Man and you’ll get some notion of the cascading audacity. This is a satire about foreign invasion in which America (in the form of Bernhard, a spiritual “golf guru”), then Japan, and finally extraterrestrials in a spaceship all turn up to claim the land down under as their own. Along the way Turner gives us delightfully incoherent dream sequences, bouts of strip miniature golf, some hilarious lampooning of the new-age mentality, and one of my favorite performances by a dog. Incidentally, Bernhard despises this movie and trashes it whenever she gets a chance, but I liked it as well as or better than many of her routines. Read more