From the Chicago Reader (November 24, 1995). — J.R.

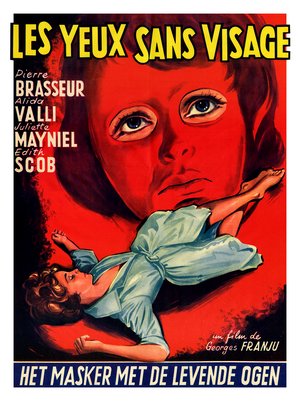

Eyes Without a Face

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Georges Franju

Written by Jean Redon, Pierre Boileau, Thomas Narcejac, Claude Sautet, Pierre Gascar, and Franju

With Edith Scob, Pierre Brasseur, Alida Valli, Juliette Mayniel, Béatrice Altariba, François Guerin, Alexandre Rignault, and Claude Brasseur.

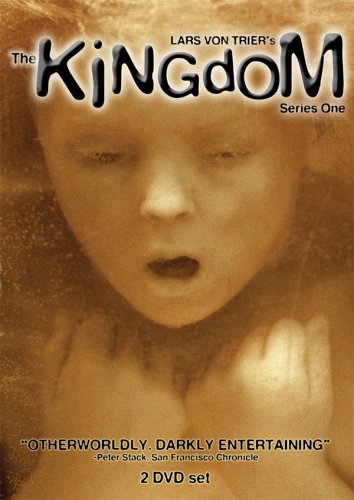

The Kingdom

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Lars von Trier and Morten Arnfred

Written by von Trier, Niels Vorsel, and Tomas Gislason

With Ernst Hugo Jaregard, Kirsten Rolffes, Ghita Norby, Soren Pilmark, Holger Juul Hansen, Annevig Schelde Ebbe, Jens Okking, Otto Brandenburg, Baard Owe, and Birgitte Raabjerg.

They’re both arty European fantasy meditations on the medical profession — that’s about all that Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face (1959) and Lars von Trier’s The Kingdom (1993) have in common, apart from the fact that they’re both opening here the day after Thanksgiving. The differences between them are much more instructive. Franju’s Les yeux sans visage is a poetic, compact (88 minutes) black-and-white French horror picture about skin grafting that premiered inauspiciously in the United States 32 years ago in a dubbed and reportedly mangled version known as The Horror Chamber of Dr. Faustus; happily, Facets Multimedia is showing it in its original form and subtitled. Read more