I believe this was commissioned by the San Francisco International Film Festival in 1993; my thanks to Adrian Martin for reminding me of its existence. — J.R.

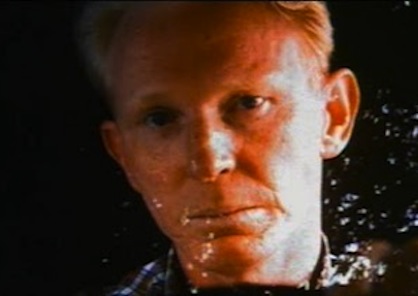

Jon Jost’s three features starring Tom Blair display a surprising amount of consistency and continuity. Part of this undoubtedly stems from the singular power and intelligence of Blair — mainly known as a stage actor and director — who is officially credited for “additional dialogue” only in The Bed You Sleep In, but undoubtedly played a comparable role in earlier films. Another part just as surely comes from the way in which Blair’s particular talents have inspired and inflected some of Jost’s preoccupations. All three films focus on specific forms of all-American male dementia and violence, crumbling economies and communities and family units that come apart through contagious paranoid mistrust. And all three can be further read in part as corrosive, speculative self-portraits that reflect his changing position as a filmmaker. When he made Last Chants for a Slow Dance (Dead End) he was effectively without a fixed address himself and his searing look at the misogyny and wanderlust of Tom, driving around jobless and in flight from domesticity, is in part a dark reading of his own situation at the time. Read more