From Monthly Film Bulletin, October 1974 (Vol. 41, No. 489). -– J.R.

Great Britain, 1973

Director: Saul Bass

Ernest Hubbs, a research scientist, sets up an experimental dome in the Arizona of the resident ant population: the various species have united and are collectively destroying all their natural enemies. With the help of James Lesko, a colleague versed in computer analysis, Hubbs orders the Eldridge family to evacuate the area, and blasts the enormous anthills with grenades. When the Eldriges’ belateddeparture is precipitated by an ant attack, they are further incapacitated by the poison gas being used against the insects. Kendra, the granddaughter, is the only survivor, and is brought into the dome in a state of shock. The ants develop an immunity to the poison gas, and a subsequent experiment with mantises is foiled when Kundra hysterically smashes the lab equipment, causing Hubbs to be bitten on the hand by several ants. The ants ‘attack’ the dome with heat-focusing mirror surfaces, putting the computers out of commission; Lesko fights back with ‘white sound’, but the ants next succeed in destroying the dome’s air-conditioning unit. Lesko transmits a rectangular drawing to the ants in an effort to communicate, and receives in reply an identical drawing with a small circle containing a dot inside. Kendra interprets this to mean that the ants want her, and secretly leaves the dome. Hubbs, crazed by his ant bites, also leaves, bent on destroying the queen of the ants, but falls info a pit where the ants devour him. Lesko, attempting to fulfill Hubbs’ mission, enters an underground chamber and finds Kendra there. He realizes that the ants want both of them, for some unspecified reason, and that they will both be changed and made a part of the ants’ world.

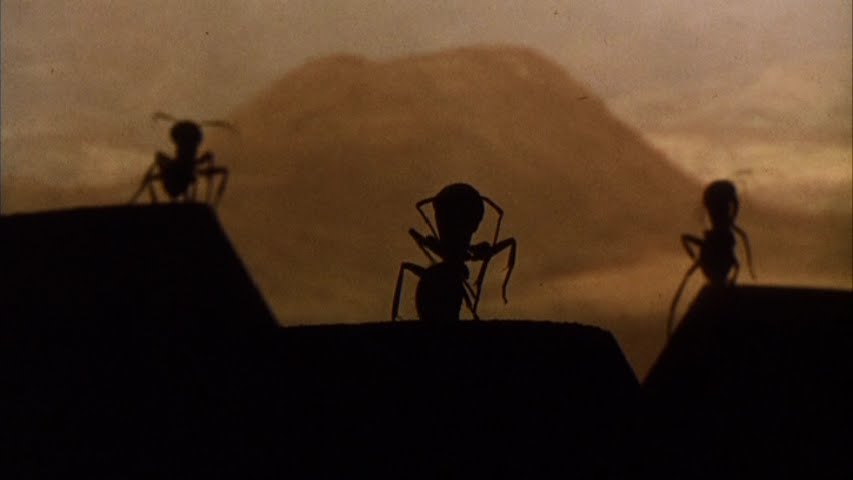

From its opening shot — the earth in orbit around the sun, accompanied by electronically devised ‘celestial’ voices — Saul Bass’ first feature signals an almost abject reliance on various science fiction works that have preceded it: 2001 first and last, Orson Welles’ War of the Worlds broadcast in the narration (begun by Hubbs, and after his death taken up by Lesko), the delimited use of enclosed space from The Thing in the experimental dome, and a trio of archaic stock figures (mad scientist, healthy romantic- lead sidekick, orphaned teenage girl) derived from some of the pulpier manifestations of the genre. Yet despite these embarrassing playbacks, and the stilted performances, which make them even less tenable, Phase IV cannot be written off as a film lacking either originality or talent. In keeping with his celebrated background as a designer of film credits, Bass imposes himself graphically even when he falters dramatically, and some isolated shots and sequences are impressive indeed, although they usually work against the grain of any intended suspense or narrative momentum. Many of the visual conceits seem surrealist (ants crawling out of a hole in a dead man’s hand, for example), but the overall clarity of Dick Bush’s photography — and Ken Middleham’s no less luminous footage of the ants — often suggests hyper-realism as well. The lighted interior of the Eldridges’ truck at night even briefly recalls the superb use of color in Julia Solntseva’s films. The failure of Bass to extend these virtues in the narrative itself seems to be partially a consequence of the film’s mosaic construction: cutting from the terrorized Eldridge family in medium shot to the ants in close-up fails to convince us that the ants are sufficiently present in both shots, and this flaw is symptomatic of the cross-cutting in general, which tends to splinter rather than sustain narrative interest. Plastic relationships between ants and men are occasionally established — most strikingly, in a cut from the monolith-like anthills to a row of computers inside the dome — but the dramatic relationships are perpetually suspended. One suspects that if Bass were able to eliminate actors and dialogue entirely, he might be able to pursue his graphic interests with much more continuity and distinction; saddled with an impossibly outworn string of clichés and platitudes, and an uncomfortable cast to deliver them, he has to content himself with an elegant book jacket; to house a disintegrating text.