From the Chicago Reader (October 1, 1993). — J.R.

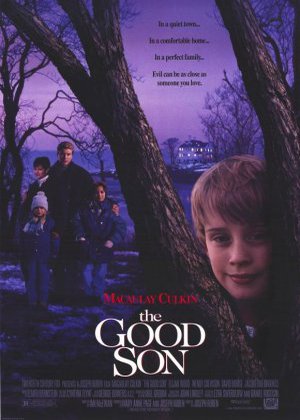

THE GOOD SON

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Joseph Ruben

Written by Ian McEwan

With Macaulay Culkin, Elijah Wood, Wendy Crewson, David Morse, Daniel Hugh Kelly, and Quinn Culkin.

The innocent-looking child who’s really evil incarnate is a natural idea for a horror movie, but getting us to believe in such a character isn’t as simple as it might sound. Ray Bradbury had a relatively easy time of it in “The Small Assassin,” a short story first published back in 1946 about an infant who murders people, because babies are somewhat mysterious and hence easier to project abstract notions on. In The Good Son, a mainly unconvincing thriller offering us 12-year-old Macaulay Culkin as evil incarnate, there are actually two problems — accepting Culkin as a child and accepting him as evil. Perhaps what we mean today by both “child” and “evil,” ideologically speaking, is at the root of the problem.

The hero of The Good Son is another boy of roughly the same age, Mark (Elijah Wood), living in the southwest, who has been traumatized by the recent death of his mother. Shortly before she dies she tells him, “I’ll always be with you,” and Mark interprets this to mean that she’ll come back to him as someone else. After the funeral Mark’s father (David Morse) discovers he has to go to Tokyo on important business, and Mark’s uncle (Daniel Hugh Kelly) convinces him to leave Mark with him and his family at their house in Maine for the few weeks he’ll be away. After befriending his cousin Henry (Culkin), Mark gradually discovers a streak of gratuitous cruelty in him to which everyone else — uncle, aunt (Wendy Crewson), Henry’s kid sister Connie (Culkin’s kid sister Quinn), and a local child psychologist (Jacqueline Brookes) — is completely oblivious. Meanwhile, Mark becomes convinced that his aunt, who is still grieving the apparently accidental death of her youngest child, is the reincarnation of his mother.

There are two forms of innocent gullibility at work here — Mark’s beliefs about his aunt, and everyone else’s blindness about Henry’s true nature — and in terms of thriller mechanics they don’t mesh very well. We can’t entirely share Mark’s point of view because of his reincarnation hang-up, and everyone else’s blindness to Henry’s cruelty and hypocrisy makes them seem like a pack of blithering idiots. If screenwriter Ian McEwan had stuck to either premise and shown more sensitivity to its psychological ramifications, the movie might have worked, either as a psychological mood piece a la Val Lewton (the reincarnation scenario) or as a straight paranoid thriller. Unfortunately McEwan doesn’t work very hard at getting us to accept either idea. The movie almost never convinces us even of the simplest thing: that we’re watching the behavior of 12-year-olds. Both boys indulge in play that makes them seem a lot younger, while at least one of Henry’s pithy one-liners to Mark — “Don’t fuck with me” — suggests that we’re supposed to take him as a pint-size adult.

I’ve never read William March’s novel The Bad Seed or seen the popular Maxwell Anderson play derived from it, but I can still recall the ludicrous way the play was turned into a Hollywood movie in 1956. The title heroine, played by Patty McCormack, was an eight-year-old murderer in pigtails, and when her mother discovered the girl’s monstrous nature and crimes, she gave her an overdose of sleeping pills and then took her own life. The play’s surprise twist was that the girl survived, presumably free to go on killing. The producers of the movie clearly found this macabre conclusion unthinkable — not surprisingly, given the premium placed on middle-class childhood innocence in the 50s — so they thoughtfully arranged to have their homicidal heroine dispatched by a bolt of lightning. And then, to show they were only fooling, they ended the movie with a literal curtain call for the actors, resurrecting the mother (Nancy Kelly) so she could jokingly punish the girl with a good, sound spanking.

Thirty-seven years later the audience is no longer presumed innocent in quite the same way, even theoretically, and The Good Son never stoops to any such forms of cautionary hysteria. This time around the innocent-looking child star can’t even be regarded as innocent; Culkin is after all a kid whose penchant for middle-class sadism and cruelty has already been celebrated at length in Home Alone and its sequel. The first of these pictures, one should recall, came out during the Persian Gulf massacre, when taking pleasure in territorial imperatives and wreaking misery on undesirables was a national pastime. Evil in our culture nowadays, as opposed to 1956, is often less a conventional, well-defined form of behavior than it is an excuse for providing violent spectacles for an audience’s delectation, either in the form of nasty acts (the fun and games of Hannibal Lecter or Saddam Hussein) or as retribution (Culkin’s pranks in Home Alone) — and sometimes as both in tandem (as in Cape Fear and Cliffhanger).

Part of the idea about “pure evil” The Good Son asks us to accept — a common one in recent movies — is that it comes out of nowhere and has no social basis whatsoever. “What makes people evil?” Mark asks the psychologist — not long after Henry has killed an unfriendly dog, caused multiple collisions on a highway, and threatened to dispose of his little sister — and she sensibly responds, “There’s a reason for everything if you just find it.” But when she admits that she doesn’t believe in evil, and he replies, adultlike, “You should,” it’s clear that the filmmakers are backing Mark’s point of view — that evil just is — perhaps out of sheer laziness. After all, if they had to establish a basis for Henry’s behavior they might have felt obliged to think about him as a character. (The best psychological explanation they can come up with, quite late in the film, is sibling rivalry with his late brother.)

If director Joseph Ruben doesn’t seem to have much sense of how kids behave, at least he does wonderful things with his location: a New England town and the surrounding landscape. One can amuse oneself reflecting on good movies that might be shot in these settings. One such movie even takes shape momentarily toward the end of The Good Son, when Ruben starts cutting effectively to overhead angles of the action in both the interiors and exteriors, which conveys a startling sensation of vertigo. And Ruben works up to an effectively hyperbolic climax that involves a sort of action paraphrase of the scene depicting “Sophie’s choice” in the novel (and inferior movie) of that title. Maybe next time he’ll have a script with characters one can believe in — something that for me hasn’t happened since he directed The Stepfather in 1987 — and we’ll really have something to write home about.