This review was originally written for the long-defunct Canadian film magazine Take One during the same time that I was writing my first book, Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (1980), and I’m sure that Pryor’s passionate form of self-examination and autocritique struck a very personal chord for me at the time. To contextualize this review a little further, I had recently written an angry attack on The Deer Hunter for the March issue of the same magazine, not too long after a reviewer in the Soho News had compared it favorably to Tolstoy. –J.R.

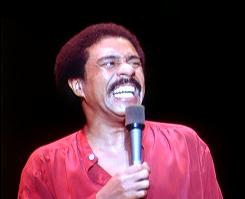

The True Auteur: Richard Pryor Live in Concert

Richard Pryor Live in Concert has nothing in particular to do with the art of cinema; it merely happens to be the densest, wisest, and most generous response to life that I’ve found this year inside a first-run movie theater. A theatrical event recorded by Bill Sargeant, the entrepreneur who similarly packaged Richard Burton’s Broadway production of Hamlet and a celebrated rock concert (The T.A.M.I. Show) fifteen years ago, and more recently filmed James Whitmore’s impersonation of Harry Truman (Give ‘Em Hell, Harry!), it is nothing more nor less than a Pryor stand-up routine given last December 28th at the Terrace Theater in Long Beach, California, lasting about an hour and a quarter. Read more